Exploring Risk Factors for Primary Liver Cancer in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Based on Machine Learning Prediction Models

-

摘要:目的

基于七种不同的机器学习算法构建慢性丙型肝炎患者发生肝癌的风险预测模型并筛选出最优模型。

方法选择236例慢性丙型肝炎患者为研究对象,以是否发生肝癌将患者分为病例组和对照组。基于决策树(CART)、随机森林(RF)、梯度提升决策树(GBDT)、极端梯度提升(XGBoost)、逻辑回归(LR)、K-近邻(KNN)、支持向量机(SVM)七种机器学习算法分别构建预测模型,针对最佳预测模型采用SHAP算法进行模型解释。

结果七种模型中,XGBoost模型的综合预测性能最好(准确率为0.933、敏感度为0.775、特异性为0.960、ROC曲线下面积为0.956、F1分数为0.764)。SHAP算法显示AFP、年龄、AST、糖尿病、BMI、PLT、ALT、肝囊肿、FIB-4、性别对模型决策贡献度较大,提示这些因素是慢性丙型肝炎患者发生肝癌的风险因素。

结论本研究构建了一种可解释的基于XGBoost算法的机器学习模型,在慢性丙型肝炎患者群体中进行肝癌个体化监测具有良好的参考价值。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo construct a risk prediction model for liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis C based on seven different machine learning algorithms and select the optimal model.

MethodsA total of 236 patients with chronic hepatitis C were selected as the research subjects. Patients were divided into a case group and a control group according to whether liver cancer occurs. Prediction models were constructed based on seven machine learning algorithms including classification and regression tree, random forest, gradient boosting decision tree, extreme gradient boosting (XGBoost), logistic regression, K-near neighbor, and support vector machine. The Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) algorithm was used to interpret the best prediction model.

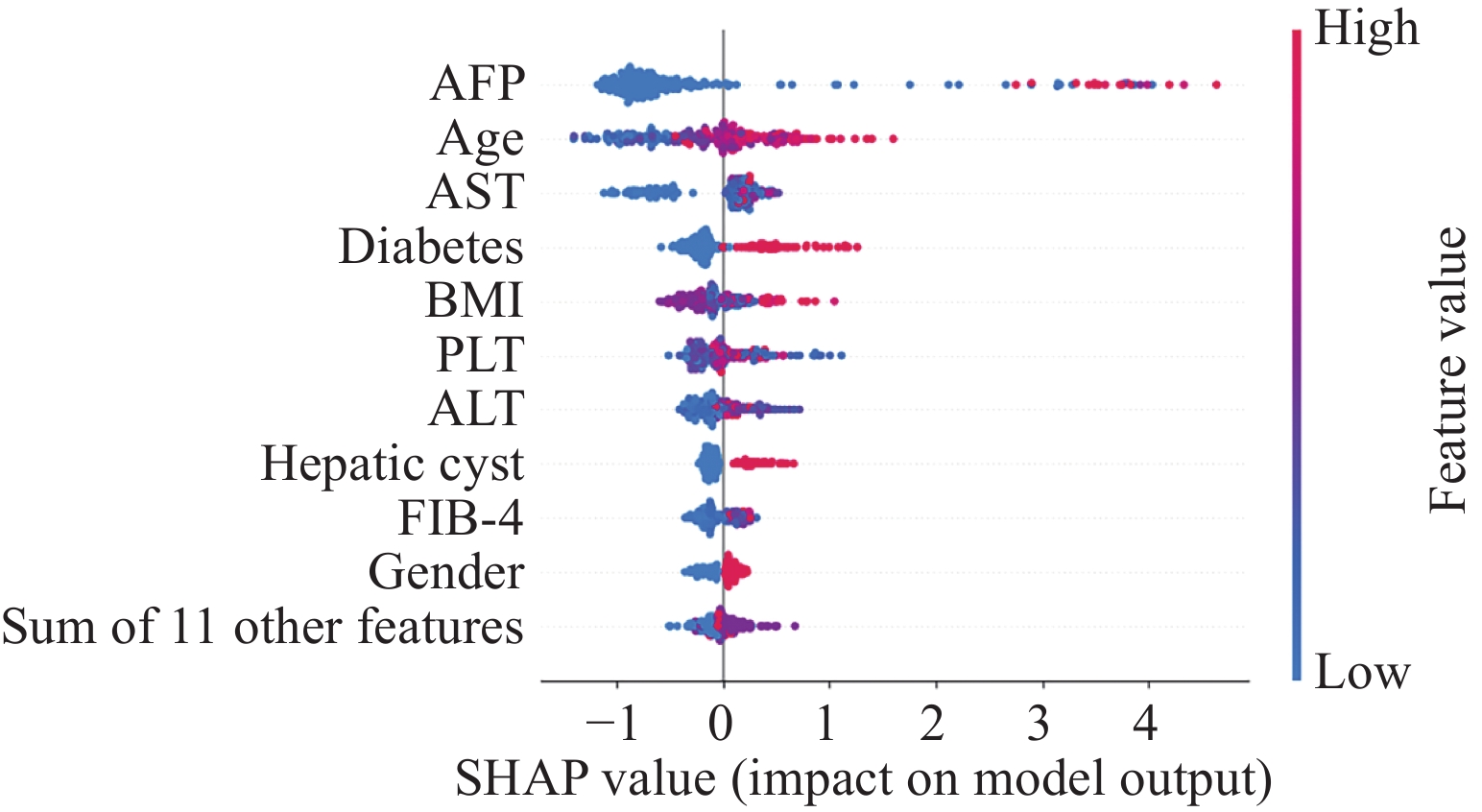

ResultsAmong the seven models, the XGBoost model had the best comprehensive prediction performance (accuracy of 0.933, sensitivity of 0.775, specificity of 0.960, area under the ROC curve of 0.956, F1 score of 0.764). The SHAP algorithm suggested that AFP, age, AST, diabetes, BMI, PLT, ALT, liver cysts, FIB-4, and gender contributed to the model decision and are the risk factors for liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

ConclusionThis study develops an interpretable machine learning model based on the XGBoost algorithm, which has a good reference value for individualized monitoring of liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis C.

-

Key words:

- Machine learning /

- Chronic hepatitis C /

- Liver cancer /

- Prediction model

-

0 引言

肝癌是全球常见恶性肿瘤之一,而我国肝癌发病和死亡人数占全球近一半[1],2022年流行病学数据显示,我国肝癌发病率位居恶性肿瘤第4位,死亡率位居恶性肿瘤第2位[2]。此外,我国肝癌患者5年生存率仅为14.1% [3],对人民健康危害很大。《“健康中国2030”规划纲要》提出,到2030年,总体癌症5年生存率提高15%[4]。要实现肝癌生存率提高的目标,需从肝癌的病因出发,降低肝癌发病率和中晚期肝癌的比例。

慢性丙型病毒性肝炎(简称慢丙肝)是肝癌的重要病因之一,症状隐匿是慢丙肝最大的特点,部分患者甚至发展成中晚期肝癌才确诊。早期肝癌与中晚期肝癌的预后差距很大,探索慢丙肝进展为肝癌的危险因素,识别高危患者,对预防丙肝向肝癌进展,改善患者预后尤为重要。

机器学习能够发现数据中的潜在规律,对临床诊断具有重要的参考价值。近年来,机器学习算法越来越多地应用于肝癌诊断领域[5-8],然而,多数研究是针对慢性乙型肝炎患者[5,7],本研究基于机器学习算法构建及筛选慢丙肝患者发生肝癌的最优风险预测模型,并采用SHAP法对模型进行可解释性分析,以期为改进丙肝相关肝癌的个体化风险预测提供参考。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

选择2016年1月至2023年12月在福建医科大学附属协和医院确诊的236例慢丙肝患者为研究对象,以是否发生原发性肝癌将患者分为病例组和对照组。纳入标准:(1)检索全院病历系统,从丙肝抗体阳性数据库、丙肝RNA阳性数据库以及出院诊断数据库中,根据病史及辅助检查结果明确诊断为慢丙肝的患者;(2)收集的各项资料信息完整。排除标准:(1)合并其他类型(甲、乙、丁、戊型)的肝炎病毒感染;(2)患有转移性肝癌或有结直肠癌手术史患者。本研究经福建医科大学附属协和医院伦理委员会批准(2024KY026)。

1.2 调查内容

收集所有患者一般资料包括性别、年龄等,临床特征包括体格检查、疾病诊断治疗、个人及家族疾病史等,生活行为方式包括吸烟史、饮酒史,检验结果包括AFP、ALT、AST、PLT,并计算谷草转氨酶与血小板比值(Aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, APRI)和纤维化指数-4(Fibrosis 4 Score, FIB-4),其中APRI= [AST(IU/L)/AST正常值上限(IU/L)/血小板计数(109/L)] ×100,FIB-4= [年龄×AST(IU/L)]/[血小板计数(109/L)× $\sqrt {{\rm{ALT}}{\text{(}} {{\rm{IU/L}}} {\text{)}}} $][9]。

1.3 研究方法

采用基础分类器和集成分类器两大类机器学习算法,其中逻辑回归(Logistic regression, LR)、决策树(Classification and regression tree, CART)、支持向量机(Structure vector machine, SVM)、K-近邻(K-near neighbor, KNN)是目前使用较广泛的基础分类器。LR是线性回归的延伸,其最大的优点在于模型可解释性。与LR类似,CART的模型可解释性好,但单个决策树通常预测结果不佳。SVM是一种强大的非线性分类器,可以优化高维数据分类的效果。KNN是一种基于距离度量的机器学习算法,原理简单成熟,但噪声和非相关性特征的存在会使其准确性降低。随机森林(Random forest, RF)是集成分类器中Bagging算法的代表,在每轮迭代中有放回地从训练集中取出训练样本,构建单个决策树,每个决策树在训练时相互独立、所依赖的特征不同,从而降低异常值的个体误差。训练完成后每个决策树都有一个分类结果,占多数的分类结果即为随机森林的最终预测结果。梯度提升决策树(Gradient boosting decision tree, GBDT)和极端梯度提升(Extreme gradient boosting, XGBoost)都是boosting算法的代表,其核心思想是通过逐步迭代将弱学习器训练成强学习器,并通过不断迭代优化损失函数来减少误差,直至模型不能优化为止。XGBoost在训练方式、正则化和并行化处理上做出了改进。

1.4 统计学方法

采用SPSS 26.0、Python3.7统计学软件进行数据分析。计数资料使用例数和百分比表示,χ2检验进行组间比较。偏态分布的计量资料运用中位数(四分位数间距)表示,非参数检验进行比较。预测模型的构建,采用完全随机取样,将全体样本以3∶1的比例划分为训练集和测试集,训练过程采用5折交叉验证,训练完成后用测试集来评价模型的预测能力。评价指标采用准确率、敏感度、特异性、ROC曲线下面积、F1分数。TreeShap[10]算法从树结构的角度近似计算每个特征的Shapley加性解释(Shapley additive explanations, SHAP)值[11-12],并将计算结果用于模型的全局解释、个体解释和患者聚类。

2 结果

2.1 两组临床特征的比较

两组患者临床特征比较结果显示,性别、年龄、现住址、肝囊肿、AFP、ALT、AST、APRI、FIB-4差异有统计学意义(P<0.05),见表1。

表 1 肝癌组与非肝癌组慢丙肝患者临床特征比较结果Table 1 Comparison of clinical characteristics between the two groupsVariable Control group

n(%)/

M(Q1-Q3)Case group

n(%)/

M(Q1-Q3)χ2/Z P Gender 9.548 0.002 Female 81(44.3) 11(20.8) Male 102(55.7) 42(79.2) Age(years) 24.552 <0.001 <40 18(9.8) 0(0.0) 40-49 40(21.9) 1(1.9) 50-59 49(26.8) 12(22.6) ≥60 76(41.5) 40(75.5) Address 7.787 0.020 Downtown of

Fuzhou69(37.7) 11(20.8) Other cities in

Fujian province99(54.1) 40(75.5) Other provinces 15(8.2) 2(3.8) BMI(kg/m2) 0.197 0.906 18.5-24 112(61.2) 32(60.4) <18.5 13(7.1) 3(5.7) >24 58(31.7) 18(34.0) Smoking history 1.805 0.179 No 102(55.7) 24(45.3) Yes 81(44.3) 29(54.7) Drinking history 0.330 0.566 No 115(62.8) 31(58.5) Yes 68(37.2) 22(41.5) History of

other tumors0.568 0.451 No 147(80.3) 45(84.9) Yes 36(19.7) 8(15.1) Family history of

malignant tumors0.001 0.980 No 169(92.3) 49(92.5) Yes 14(7.7) 4(7.5) Hypertension 0.331 0.565 No 120(65.6) 37(69.8) Yes 63(34.4) 16(30.2) Coronary heart

disease0.012 0.912 No 170(92.9) 49(92.5) Yes 13(7.1) 4(7.5) Diabetes 3.274 0.070 No 146(79.8) 36(67.9) Yes 37(20.2) 17(32.1) Non-alcoholic

fatty liver

disease2.254 0.133 No 159(86.9) 50(94.3) Yes 24(13.1) 3(5.7) Hepatic cyst 11.367 0.001 No 158(86.3) 35(66.0) Yes 25(13.7) 18(34.0) Hepatic

hemangioma1.281 0.258 No 176(96.2) 49(92.5) Yes 7(3.8) 4(7.5) Antiviral

treatment0.495 0.482 No 168(91.8) 47(88.7) Yes 15(8.2) 6(11.3) AFP(ng/ml) 81.832 <0.001 ≤25 177(96.7) 25(47.2) >25 6(3.3) 28(52.8) ALT(U/L) 10.058 0.002 ≤40 97(53.0) 15(28.3) >40 86(47.0) 38(71.7) AST(U/L) 10.731 0.001 ≤40 102(55.7) 16(30.2) >40 81(44.3) 37(69.8) PLT(×109/L) 0.317 0.853 100-300 140(76.5) 42(79.2) <100 30(16.4) 7(13.2) >300 13(7.1) 4(7.5) APRI 0.53(0.29-0.98) 1.36(0.55-2.23) −4.829 <0.001 FIB-4 2.05(1.22-3.83) 4.06(2.75-6.67) −5.181 <0.001 2.2 模型选择

将性别、年龄、现住址、BMI、吸烟史、饮酒史、其他肿瘤病史、恶性肿瘤家族史、高血压、冠心病、糖尿病、非酒精性脂肪肝、肝囊肿、肝血管瘤、是否抗病毒治疗、AFP、ALT、AST、PLT、APRI、FIB-4纳入预测模型中,采用7种算法进行模型预测,结果显示测试集在XGBoost预测模型的综合预测性能最好(准确率为0.933、敏感度为0.775、特异性为0.960、ROC曲线下面积为0.956、F1分数为0.764),见表2。

表 2 各模型训练结果对比Table 2 Comparison of training results of various modelsModel Accuracy (95%CI) Sensitivity (95%CI) Specificity (95%CI) AUC (95%CI) F1 score (95%CI) CART 0.849 0.669 0.882 0.778 0.564 (0.846-0.852) (0.658-0.680) (0.879-0.885) (0.588-0.949) (0.556-0.573) LR 0.846 0.550 0.899 0.793 0.507 (0.843-0.850) (0.539-0.561) (0.897-0.902) (0.590-0.962) (0.498-0.517) KNN 0.897 0.447 0.979 0.827 0.553 (0.895-0.900) (0.436-0.458) (0.978-0.981) (0.678-0.970) (0.542-0.564) SVM 0.896 0.436 0.979 0.876 0.543 (0.893-0.898) (0.425-0.447) (0.978-0.980) (0.747-0.973) (0.532-0.554) RF 0.916 0.660 0.961 0.891 0.689 (0.914-0.918) (0.650-0.671) (0.959-0.963) (0.770-0.984) (0.680-0.698) GBDT 0.866 0.781 0.881 0.920 0.629 (0.863-0.868) (0.772-0.790) (0.878-0.884) (0.840-0.976) (0.622-0.637) XGBoost 0.933 0.775 0.960 0.956 0.764 (0.931-0.935) (0.765-0.784) (0.959-0.962) (0.890-0.996) (0.756-0.772) Notes: CART: classification and regression tree; LR: logistic regression; KNN: K-near neighbor; SVM: structure vector machine; RF: random forest; GBDT: gradient boosting decision tree; XGBoost: extreme gradient boosting; AUC: area under ROC curve; CI: confidence interval. 2.3 模型的全局解释

选择XGBoost模型为最终预测模型并采用SHAP对慢丙肝相关肝癌患者发病风险因素进行可解释性分析,对模型贡献最大的前10个特征依次为AFP、年龄、AST、糖尿病、BMI、PLT、ALT、肝囊肿、FIB-4、性别。在慢丙肝患者中,AFP、AST、ALT、FIB-4越高,年龄越大,BMI过高或过低,PLT过高或过低,肝癌风险越高;同时患有糖尿病或肝囊肿的患者,肝癌风险更大;男性患者比女性患者发生肝癌的可能性更大,见图1。

2.4 模型的个体解释

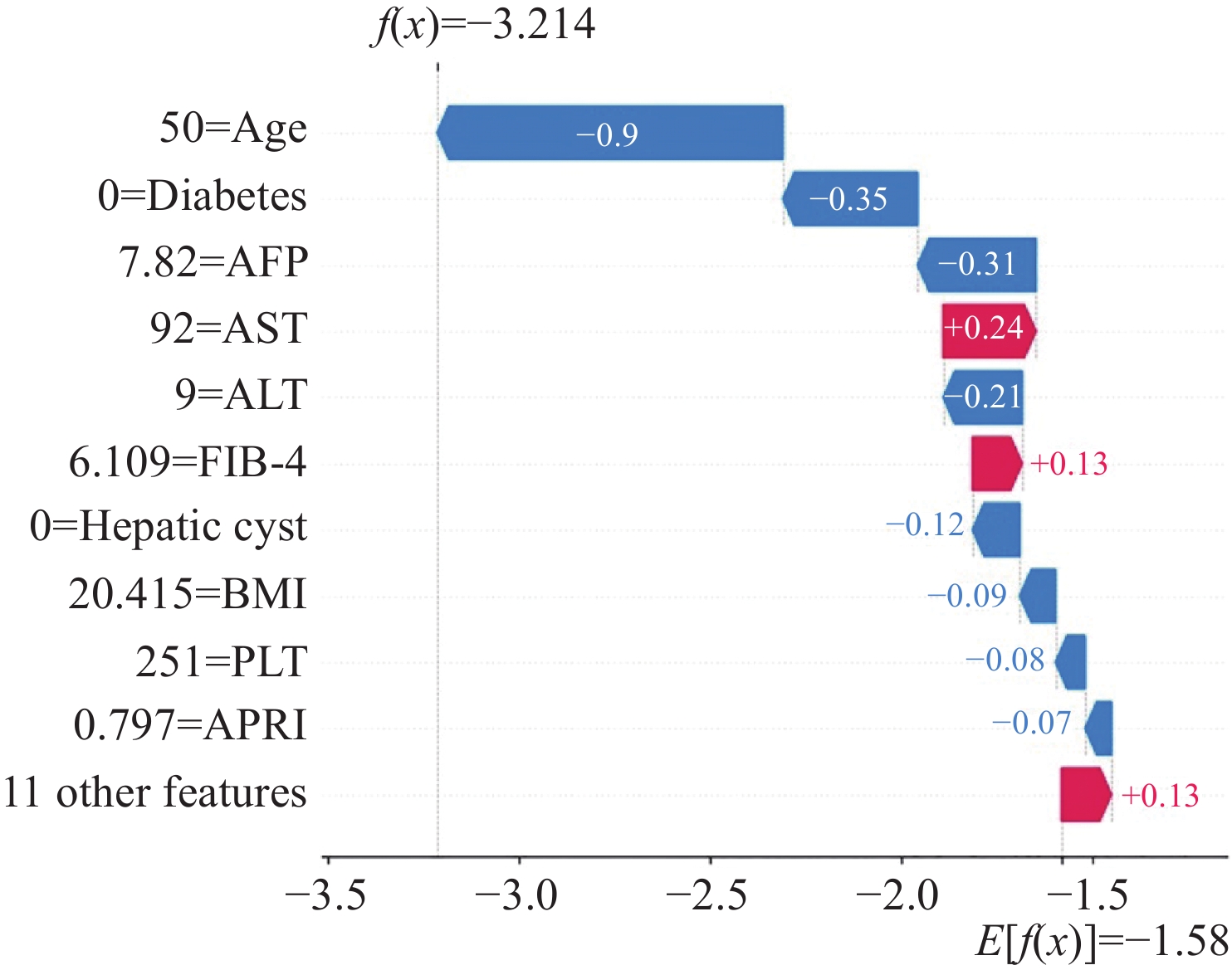

图2显示的是对照组序号为11的患者SHAP值结果。对该患者而言,年龄、无糖尿病、AFP、ALT、无肝囊肿、BMI、PLT、APRI是肝癌发生的保护因素,AST、FIB-4是肝癌发生的危险因素。该例患者SHAP值为−3.214,模型基础预测值为−1.580,提示该患者发生肝癌的可能性较小,预测结果与实际情况一致。

2.5 基于模型的患者聚类

K-means聚类法对所有患者进行聚类分析,将慢丙肝患者归为四个亚组,分别为以高AFP为标志性特征的高风险亚组,见图3A;以高龄及合并糖尿病为主要特征的高风险亚组,见图3B;以低AFP为主要特征的低风险亚组,见图3C;以低龄及低AFP为主要特征的低风险亚组,见图3D。

3 讨论

丙型肝炎病毒是肝癌的主要病因之一,全世界约30%的肝癌是由HCV感染引起的。已有研究表明,性别、年龄、患有肝病,AFP、糖尿病、BMI偏高、ALT升高、血小板减少,FIB-4是丙肝相关肝癌的重要风险因子[13-21]。本研究结果与以上报道结果一致。近年来通过抗病毒药物根除丙肝病毒,一定程度上降低了丙肝患者进展为肝癌的风险。然而,有研究表明肝癌仍会发生在已进行抗病毒治疗的慢丙肝患者中,可能与先前存在的炎性反应和肝纤维化背景、宿主与病毒相互作用之间的免疫失调,以及遗传易感和变异等有关[22]。本研究结果未显示抗病毒治疗是慢丙肝患者发生肝癌的保护因素,可能与早期抗病毒治疗尚不规范、回访时间不够长及个体差异有关,需要进一步研究验证。

相对于传统模型,机器学习可以对不同变量之间复杂、多维、非线性的关系进行建模,充分考虑临床参数之间所有潜在的相互作用,有助于辅助临床早诊断早决策。目前不同算法的机器模型准确率存在一定的差异。其中XGBoost算法因其生成的模型稳健且准确,同时具有抗过度拟合能力、处理不相关特征的能力以及相对于其他算法的多功能性,成为众多研究者的选择[23]。本研究7种机器学习算法结果显示,XGBoost模型综合预测性能最佳,与Kucukakcali等[24]、Mao等[25]关于肝癌诊断研究中不同机器学习预测模型的稳健性结果一致。本研究中GBDT和RF两种模型预测性能仅次于XGBoost。Dai等[26]及Ni等[27]对肝癌微血管侵犯预测的机器学习研究中,GBDT模型的准确率最高。而Minami等[28]研究报道,对慢丙肝患者采用5种机器学习模型以及传统模型进行肝癌发生的预测,结果显示RF模型预测效果最佳,且年龄和AFP为模型中最重要的两个特征变量,与本研究结果的前两位危险因素一致。

机器学习模型的可解释性对于医工交叉研究和临床应用非常重要。Shapley值概念源自联盟博弈理论,它表示特征值在所有可能情况下对模型预测值的平均边际贡献[12],是唯一满足效率、对称性、虚值和可加性的机器学习可解释性方法。SHAP值法[11]在Shapley值概念基础上,提出了更高效的估计方法,可以在全局和局部上解释模型的输出,从而弥补机器学习模型可解释性差的局限性。我们利用SHAP方法建立了慢丙肝患者发生肝癌危险因素的重要性排序,并对模型进行了解释,有助于提升临床医生对机器学习模型应用的信任度。此外我们对所有观测值的SHAP值进行聚类,将相似的病例进行归类,对疾病亚型分类具有潜在的指导意义。

本研究尚存在以下局限性:首先,样本量较小,为了证明模型普遍适用性,有待进一步大样本独立队列的研究验证。其次,除外本研究已纳入的基础临床信息,模型还需要更多的数据源进一步优化,例如影像数据(包括超声、CT、MRI)、病理数据、基因数据等等,综合图像、声音、文本的多模态数据有望进一步提升模型的预测效果。

综上所述,本研究基于机器学习算法构建了关于慢丙肝患者发生肝癌的可解释性风险预测模型对于在慢丙肝人群中进行个性化的危险因素筛查和监测,有效利用医疗资源,实现高危患者的早诊断早治疗具有一定的参考价值。

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。作者贡献:杨 蓉:数据收集分析、论文撰写方 斌:数据分析、统计指导郑玲玲:论文选题、审阅修改、基金支持陈锦华:统计指导周文娟:数据收集 -

表 1 肝癌组与非肝癌组慢丙肝患者临床特征比较结果

Table 1 Comparison of clinical characteristics between the two groups

Variable Control group

n(%)/

M(Q1-Q3)Case group

n(%)/

M(Q1-Q3)χ2/Z P Gender 9.548 0.002 Female 81(44.3) 11(20.8) Male 102(55.7) 42(79.2) Age(years) 24.552 <0.001 <40 18(9.8) 0(0.0) 40-49 40(21.9) 1(1.9) 50-59 49(26.8) 12(22.6) ≥60 76(41.5) 40(75.5) Address 7.787 0.020 Downtown of

Fuzhou69(37.7) 11(20.8) Other cities in

Fujian province99(54.1) 40(75.5) Other provinces 15(8.2) 2(3.8) BMI(kg/m2) 0.197 0.906 18.5-24 112(61.2) 32(60.4) <18.5 13(7.1) 3(5.7) >24 58(31.7) 18(34.0) Smoking history 1.805 0.179 No 102(55.7) 24(45.3) Yes 81(44.3) 29(54.7) Drinking history 0.330 0.566 No 115(62.8) 31(58.5) Yes 68(37.2) 22(41.5) History of

other tumors0.568 0.451 No 147(80.3) 45(84.9) Yes 36(19.7) 8(15.1) Family history of

malignant tumors0.001 0.980 No 169(92.3) 49(92.5) Yes 14(7.7) 4(7.5) Hypertension 0.331 0.565 No 120(65.6) 37(69.8) Yes 63(34.4) 16(30.2) Coronary heart

disease0.012 0.912 No 170(92.9) 49(92.5) Yes 13(7.1) 4(7.5) Diabetes 3.274 0.070 No 146(79.8) 36(67.9) Yes 37(20.2) 17(32.1) Non-alcoholic

fatty liver

disease2.254 0.133 No 159(86.9) 50(94.3) Yes 24(13.1) 3(5.7) Hepatic cyst 11.367 0.001 No 158(86.3) 35(66.0) Yes 25(13.7) 18(34.0) Hepatic

hemangioma1.281 0.258 No 176(96.2) 49(92.5) Yes 7(3.8) 4(7.5) Antiviral

treatment0.495 0.482 No 168(91.8) 47(88.7) Yes 15(8.2) 6(11.3) AFP(ng/ml) 81.832 <0.001 ≤25 177(96.7) 25(47.2) >25 6(3.3) 28(52.8) ALT(U/L) 10.058 0.002 ≤40 97(53.0) 15(28.3) >40 86(47.0) 38(71.7) AST(U/L) 10.731 0.001 ≤40 102(55.7) 16(30.2) >40 81(44.3) 37(69.8) PLT(×109/L) 0.317 0.853 100-300 140(76.5) 42(79.2) <100 30(16.4) 7(13.2) >300 13(7.1) 4(7.5) APRI 0.53(0.29-0.98) 1.36(0.55-2.23) −4.829 <0.001 FIB-4 2.05(1.22-3.83) 4.06(2.75-6.67) −5.181 <0.001 表 2 各模型训练结果对比

Table 2 Comparison of training results of various models

Model Accuracy (95%CI) Sensitivity (95%CI) Specificity (95%CI) AUC (95%CI) F1 score (95%CI) CART 0.849 0.669 0.882 0.778 0.564 (0.846-0.852) (0.658-0.680) (0.879-0.885) (0.588-0.949) (0.556-0.573) LR 0.846 0.550 0.899 0.793 0.507 (0.843-0.850) (0.539-0.561) (0.897-0.902) (0.590-0.962) (0.498-0.517) KNN 0.897 0.447 0.979 0.827 0.553 (0.895-0.900) (0.436-0.458) (0.978-0.981) (0.678-0.970) (0.542-0.564) SVM 0.896 0.436 0.979 0.876 0.543 (0.893-0.898) (0.425-0.447) (0.978-0.980) (0.747-0.973) (0.532-0.554) RF 0.916 0.660 0.961 0.891 0.689 (0.914-0.918) (0.650-0.671) (0.959-0.963) (0.770-0.984) (0.680-0.698) GBDT 0.866 0.781 0.881 0.920 0.629 (0.863-0.868) (0.772-0.790) (0.878-0.884) (0.840-0.976) (0.622-0.637) XGBoost 0.933 0.775 0.960 0.956 0.764 (0.931-0.935) (0.765-0.784) (0.959-0.962) (0.890-0.996) (0.756-0.772) Notes: CART: classification and regression tree; LR: logistic regression; KNN: K-near neighbor; SVM: structure vector machine; RF: random forest; GBDT: gradient boosting decision tree; XGBoost: extreme gradient boosting; AUC: area under ROC curve; CI: confidence interval. -

[1] Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 77(6): 1598-1606. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021

[2] 郑荣寿, 陈茹, 韩冰峰, 等. 2022年中国恶性肿瘤流行情况分析[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2024, 46(3): 221-231. [Zheng RS, Chen R, Han BF, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2024, 46(3): 221-231.] doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240119-00035 Zheng RS, Chen R, Han BF, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2022[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2024, 46(3): 221-231. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112152-20240119-00035

[3] He S, Xia C, Li H, et al. Cancer profiles in China and comparisons with the USA: a comprehensive analysis in the incidence, mortality, survival, staging, and attribution to risk factors[J]. Sci China Life Sci, 2024, 67(1): 122-131. doi: 10.1007/s11427-023-2423-1

[4] 中共中央国务院印发《“健康中国2030”规划纲要》[J]. 中华人民共和国国务院公报, 2016, (32): 5-20. [The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and The State Council issued the Outline of Healthy China 2030[J]. Zhonghua Ren Min Gong He Guo Guo Wu Yuan Gong Bao, 2016, (32): 5-20.] The Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and The State Council issued the Outline of Healthy China 2030[J]. Zhonghua Ren Min Gong He Guo Guo Wu Yuan Gong Bao, 2016, (32): 5-20.

[5] Yip TCF, Yurdaydin C. Improving prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B by machine learning: Productive relationship of medicine with computer science[J]. Liver Int, 2023, 43(8): 1626-1628. doi: 10.1111/liv.15631

[6] Johnson PJ, Bhatti E, Toyoda H, et al. Serologic Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Application of Machine Learning and Implications for Diagnostic Models[J]. JCO Clin Cancer Inform, 2024, 8: e2300199.

[7] Kim HY, Lampertico P, Nam JY, et al. An artificial intelligence model to predict hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Korean and Caucasian patients with chronic hepatitis B[J]. J Hepatol, 2022, 76(2): 311-318. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.09.025

[8] Angelis I, Exarchos T. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2021, 1338: 21-29.

[9] Lai M, Afdhal NH. Liver Fibrosis Determination[J]. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2019, 48(2): 281-289. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2019.02.002

[10] Lundberg SM, Erion G, Chen H, et al. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees[J]. Nat Mach Intell, 2020, 2(1): 56-67. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0138-9

[11] Lundberg SM, Nair B, Vavilala MS, et al. Explainable machine-learning predictions for the prevention of hypoxaemia during surgery[J]. Nat Biomed Eng, 2018, 2(10): 749-760. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0304-0

[12] Linardatos P, Papastefanopoulos V, Kotsiantis S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods[J]. Entropy (Basel), 2020, 23(1): 18. doi: 10.3390/e23010018

[13] Ye W, Siwko S, Tsai RYL. Sex and Race-Related DNA Methylation Changes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(8): 3820. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083820

[14] Farooq HZ, James M, Abbott J, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with hepatitis C genotype 3 infection: A systematic review[J]. World J Gastrointest Oncol, 2024, 16(4): 1596-1612. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v16.i4.1596

[15] Suh JK, Lee J, Lee JH, et al. Risk factors for developing liver cancer in people with and without liver disease[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(10): e0206374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206374

[16] Ji D, Chen GF, Niu XX, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is a risk factor for occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virologic response in chronic hepatitis C patients: A prospective four-years follow-up study[J]. Metabol Open, 2021, 10: 100090. doi: 10.1016/j.metop.2021.100090

[17] Mohamed AA, Omran D, El-Feky S, et al. Toll-like receptor 7 mRNA is reduced in hepatitis C-based liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, out-performs alpha-fetoprotein levels, and with age and serum aspartate aminotransferase is a new diagnostic index[J]. Brit J Biomed Sci, 2021, 78(1): 18-22. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2020.1778842

[18] Wong A, Le A, Lee MH, et al. Higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanic patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and metabolic risk factors[J]. Sci Rep, 2018, 8(1): 7164. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25533-2

[19] Azit NA, Sahran S, Voon Meng L, et al. Risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in type 2 diabetes patients: A two-centre study in a developing country[J]. PLoS One, 2021, 16(12): e0260675. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0260675

[20] Ho SY, Wang LC, Hsu CY, et al. Metavir Fibrosis Stage in Hepatitis C-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Association with Noninvasive Liver Reserve Models[J]. J Gastrointest Surg, 2020, 24(8): 1860-1862. doi: 10.1007/s11605-020-04627-1

[21] Quaranta MG, Cavalletto L, Russo FP, et al. Reduction of the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma over Time Using Direct-Acting Antivirals: A Propensity Score Analysis of a Real-Life Cohort (PITER HCV)[J]. Viruses, 2024, 16(5): 682. doi: 10.3390/v16050682

[22] Huang CF, Awad MH, Gal-Tanamy M, et al. Unmet needs in the post-DAA era: the risk and molecular mechanisms of hepatocellular carcinoma after HCV eradication[J]. Clin Mol Hepatol, 2024, 30(3): 326-344.

[23] Gil-Rojas S, Suárez M, Martínez-Blanco P, et al. Application of Machine Learning Techniques to Assess Alpha-Fetoprotein at Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2024, 25(4): 1996. doi: 10.3390/ijms25041996

[24] Kucukakcali Z, Akbulut S, Colak C. Machine Learning-based Prediction of HBV-related Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Detection of Key Candidate Biomarkers[J]. Medeni Med J, 2022, 37(3): 255-263. doi: 10.4274/MMJ.galenos.2022.39049

[25] Mao B, Zhang L, Ning P, et al. Preoperative prediction for pathological grade of hepatocellular carcinoma via machine learning-based radiomics[J]. Eur Radiol, 2020, 30(12): 6924-6932. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07056-5

[26] Dai H, Lu M, Huang B, et al. Considerable effects of imaging sequences, feature extraction, feature selection, and classifiers on radiomics-based prediction of microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma using magnetic resonance imaging[J]. Quant Imaging Med Surg, 2021, 11(5): 1836-1853. doi: 10.21037/qims-20-218

[27] Ni M, Zhou X, Lv Q, et al. Radiomics models for diagnosing microvascular invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma: which model is the best model?[J]. Cancer Imaging, 2019, 19(1): 60. doi: 10.1186/s40644-019-0249-x

[28] Minami T, Sato M, Toyoda H, et al. Machine learning for individualized prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma development after the eradication of hepatitis C virus with antivirals[J]. J Hepatol, 2023, 79(4): 1006-1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.05.042

下载:

下载: