-

摘要:

肝细胞癌是我国高发病率、高死亡率的癌症之一,其早期临床表现常较隐匿,导致多数患者确诊时已进展至癌症中晚期而错失手术治疗机会。目前对于这部分患者,尽管已有系统性抗肿瘤、局部放疗、介入治疗及肝移植等多种手段,甚至通过新辅助治疗可以将部分初始不可切除的肝癌转化为可切除肝癌,但仍有许多患者无法从中获益,因此迫切需要寻找新的治疗靶点。癌症相关成纤维细胞(CAFs)是实体肿瘤微环境的主要成分之一,对癌细胞增殖、迁移、侵袭和治疗抵抗等起重要作用。本综述介绍了CAFs的起源及CAFs对肝细胞癌发生和进展等方面的作用机制,阐述了靶向CAFs的潜在治疗策略。

Abstract:Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the cancers with the highest incidence and mortality rates in China and often presents with insidious early clinical manifestations. This frequency results in the majority of patients being diagnosed at middle and advanced stage of the disease, thereby missing the opportunity for potentially curative surgical interventions. For patients who are ineligible for radical surgical resection, a variety of therapeutic approaches, including systemic antitumor therapy, local radiotherapy, interventional treatment, and liver transplantation, have been employed. Moreover, neoadjuvant therapies have transformed a subset of initially unresectable HCC cases into operable ones. Nevertheless, many patients fail to benefit from these treatments, underscoring the urgent need for novel therapeutic targets. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), a principal component of the solid tumor microenvironment, play a pivotal role in the proliferation, migration, invasion, and treatment resistance of cancer cells. This review delineates the origins of CAFs and their mechanisms of action in the pathogenesis and progression of HCC and discusses potential therapeutic strategies targeting CAFs.

-

0 引言

肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma, HCC)是原发性肝癌的主要类型(约占90%),其癌症相关死亡率高居全球第三[1],在中国、韩国等许多国家,超半数肝细胞癌患者确诊时已处于中晚期[2],现有的治疗手段总体疗效并不理想。随着研究的深入,学者们发现癌细胞能够通过不断改造肿瘤微环境(tumor microenvironment, TME)来促进自身发展和逃避免疫监视[3],靶向TME可能会成为一种重要的抗癌途径。TME是由细胞组分(包括癌细胞、成纤维细胞、血管内皮细胞、免疫细胞和神经细胞)和非细胞组分(如细胞外基质(extracellular matrix, ECM)、生长因子、趋化因子、细胞因子和细胞外囊泡)共同构成的复杂网络[4-6]。癌症相关成纤维细胞(cancer associated fibroblasts, CAFs)作为TME中的关键成分,对肝细胞癌的发生和发展起着至关重要的作用[7]。

1 癌症相关成纤维细胞

CAFs是TME中主要细胞成分之一,具有高度异质性,在肿瘤增殖、侵袭、转移、免疫逃逸、血管生成等方面发挥着关键作用,值得注意的是,CAFs也可能具有抑癌作用,有证据表明表达Ⅰ型胶原的肌成纤维细胞能够通过在空间上限制肿瘤体积的增加而抑制肿瘤生长[8-9]。

1.1 CAFs的来源和激活

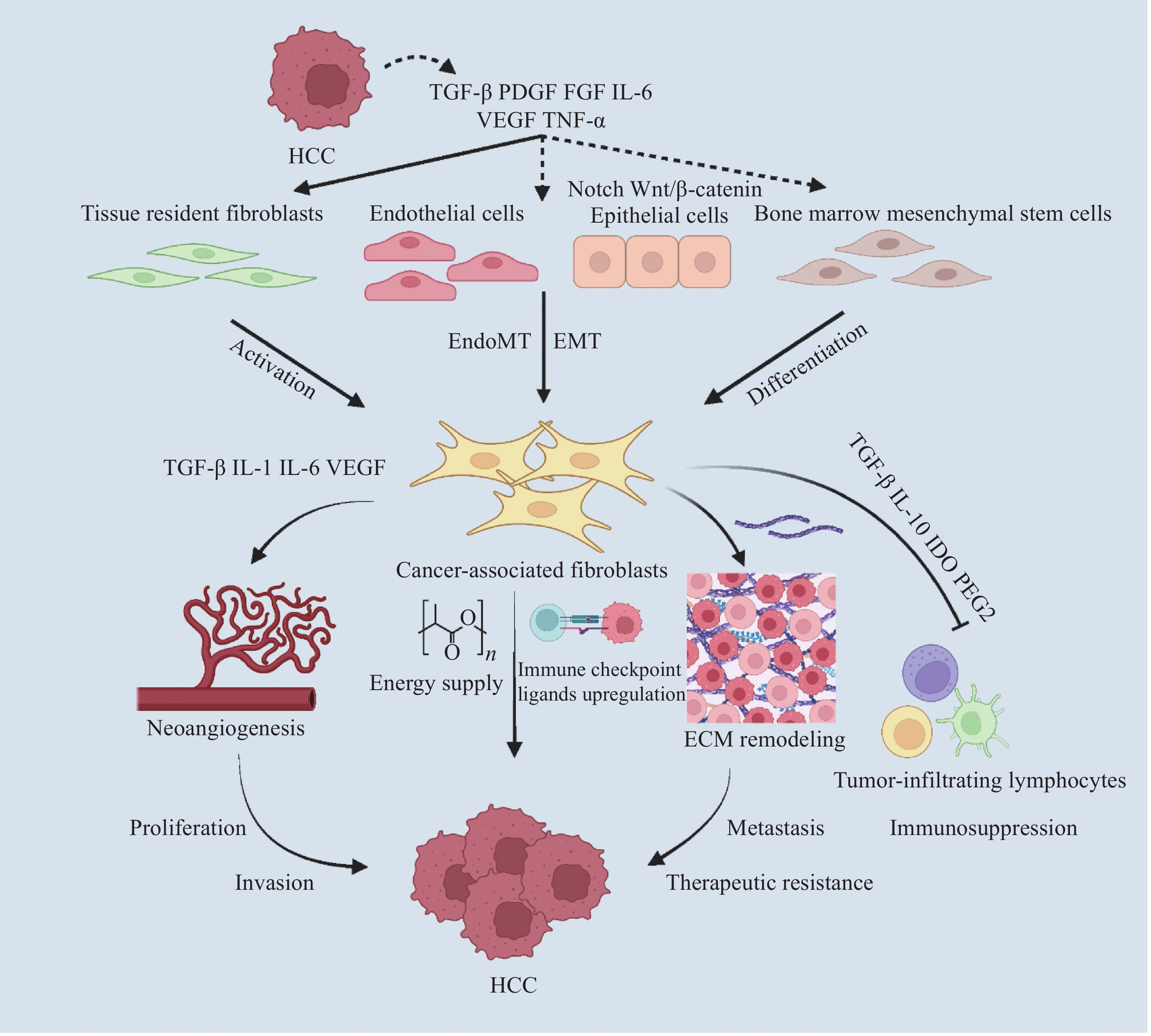

目前研究普遍认为CAFs来源于多种细胞类型[7,10-12],活化的CAFs通常表达一系列标志物,如α-平滑肌肌动蛋白(alpha smooth muscle actin, α-SMA)、成纤维细胞活化蛋白α(fibroblast activating protein alpha , FAP)、成纤维细胞特异性蛋白1(fibroblast specific protein 1, FSP-1)和血小板源性生长因子受体(platelet-derived growth factor receptors, PDGFR)等[13-15]。TME中的癌细胞和其他细胞能够分泌多种细胞因子、生长因子和趋化因子,如转化生长因子-β(transforming growth factor-β, TGF-β)、血小板衍生生长因子(platelet-derived growth factor, PDGF)、纤维细胞生长因子(fibroblast growth factor, FGF)、肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor-alpha, TNF-α)和白细胞介素-6(interleukin-6, IL-6)等,组织固有的成纤维细胞或成纤维样细胞(如肝脏或胰腺的星状细胞)[16]能在这些因子刺激下被激活而获得CAFs表型。此外,上皮细胞、内皮细胞以及骨髓间充质干细胞在特定信号分子的作用下(如TGF-β、Notch信号通路、Wnt/β-catenin信号通路等),能通过上皮/内皮-间质转化(epithelial-mesenchymal transition, EMT/Endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition, EndoMT)等方式转分化为CAFs,在此过程中它们会丧失原有的特异性标志(如CD31或VE-cadherin),并开始表达间质标志物(如α-SMA、FSP-1、vimentin等)。在不同类型的实体肿瘤中,CAFs的来源不同,其特异性标志物可能也有所不同。例如,与肝脏转移相关的CAFs通常源自肝星状细胞(hepatic stellate cells, HSCs),表达HSCs的特异性标志物(如CD38、CD117)[9]。

1.2 CAFs在肿瘤中的基本功能

大多数情况下,活化的CAFs发挥促癌作用,主要为以下方面:(1)促进癌细胞生长 CAFs能够通过分泌生长因子如TGF-β、IL-1、IL-6、血管内皮生长因子(vascular endothelial growth factor, VEGF)等因子,促进炎性反应并推动新生血管形成,从而促进癌细胞的增殖和存活[17-19];(2)调节TME CAFs能够重塑ECM的成分和结构,比如增加胶原蛋白的沉积以提升组织刚性,帮助癌细胞生长和转移,还可形成伪足并分泌基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinases, MMPs)来降解周围ECM,进一步促进癌细胞侵袭;(3)影响免疫反应 CAFs能够通过分泌TGF-β、IL-10、吲哚胺2,3-双加氧酶(indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase, IDO)、前列腺素E2(prostaglandin E2, PGE2)等免疫抑制因子抑制T细胞的活化和功能[20-21],减少抗原呈递和促进抑制性免疫细胞增殖(如调节性T细胞Treg)等,并且还能上调癌细胞免疫检查点配体的表达,促进免疫逃逸;(4)参与代谢调节 CAFs还可以通过改变自身的代谢来支援癌细胞的生长,例如通过分泌高能代谢产物供癌细胞利用[22-23];(5)治疗抵抗 CAFs通过直接与癌细胞相互作用或改变TME促进癌细胞对某些药物的抵抗。

研究显示,TME中CAFs的数量与肿瘤的体积正相关,且通常提示不良预后[24-25]。然而,由于缺乏特异性细胞标志物,针对CAFs的体内研究仍面临诸多挑战。

2 CAFs在肝细胞癌中的作用

2.1 抑制免疫系统抗癌能力和诱导癌症干性

最近研究发现,部分接受过PD-1/PD-L1免疫治疗的肝细胞癌患者,其癌肿核心区周围会形成屏障样结构,这种屏障是由CAFs和SPP1+巨噬细胞通过配体-受体相互作用,促进细胞外间质的重塑共同形成的。它的存在显著减少了免疫细胞在癌灶核心区域的浸润,抑制了效应T细胞、NK细胞的杀伤能力,从而削弱了免疫治疗效果[26]。此外,研究还发现CAFs能通过CD36介导的脂质过氧化诱导p38激酶磷酸化从而激活下游转录因子CEBP与迁移抑制因子(migration inhibitory factor, MIF)的启动子直接结合。MIF表达上调促使骨髓来源抑制细胞(myeloid-derived suppressor cells, MDSCs)扩增并在HCC中聚集,大量MDSCs不仅能借助诱导型一氧化氮合酶(nitric oxide synthase, iNOS)抑制效应T细胞和NK细胞的功能,还能通过IL-6介导的STAT3激活促进癌症干性[27],其他研究也指出,CAFs能影响中性粒细胞和NK细胞的功能,通过不同的途径减弱它们的抗癌活性,例如通过IL-6/STAT3通路诱导产生PD-L1+中性粒细胞,或通过分泌PGE2和IDO减少NK细胞的活性[28-29]。Zhao等研究者发现,在HCC中,CAFs高表达SCUBE1蛋白,它通过激活Shh(Sonic Hedgehog)/Gli1通路增加癌症干性[30-31]。

综上所述,CAFs在HCC中大量存在,对TME结构和功能有重要作用。CAFs一方面可以抑制癌症浸润免疫细胞的增殖和活化,使癌细胞能抵御免疫杀伤,另一方面能够通过多种途径促进癌症干性,维持癌细胞的增殖,增强其远处转移能力。

2.2 分泌促癌相关因子和激活癌症相关通路

有研究表明,在HCC中CAFs来源的心肌营养素样细胞因子1(cardiotrophin-like cytokine factor 1, CLCF1)能使癌细胞分泌更多趋化因子配体6(chemokine ligand 6, CXCL6)和TGF-β。CXCL6通过激活PI3K/Akt或NF-κB信号促进癌症进展,而TGF-β则增加了癌症干细胞的产生。CLCF1的高表达使CLCF1-CXCL6/TGF-β级联反应逐渐增强,进而招募更多的肿瘤相关中性粒细胞(tumor-associated neutrophile, TAN),并将它们极化为“N2”表型。N2型TAN对癌细胞侵袭、血管生成及癌症干性有显著促进作用[32]。另外,HCC细胞分泌的CXCL6和TGF-β可以通过激活CAFs的细胞外信号调节激酶(ERK)1/2信号,以正反馈方式产生更多的CLCF1,进一步增强癌症干性。卵泡抑素样蛋白1(follistatin-like protein 1, FSTL1)是一种主要由CAFs分泌的促炎因子,FSTL1与HCC细胞上的TLR4受体结合后通过影响AKT/mTOR/4EBP1信号通路提升癌症干性。有研究发现,长链非编码RNA牛磺酸上调基因1(taurine up-regulated gene 1, TUG1)能通过沉默Kruppel样因子KLF2(一种癌症抑制因子)促进HCC细胞的增殖[33],另一项研究则表明CAFs分泌的外泌体可以释放TUG1,通过miR-524-5p/SIX1轴促进HCC细胞糖酵解[34],由此推测CAFs能以释放含有TUG1外泌体的方式增加HCC细胞的供能,从而促进其增殖和转移。

上述研究均表明,CAFs可以分泌多种细胞因子、趋化因子和生长因子,与癌细胞及其他细胞互作,激活癌症相关信号通路,发挥多种促癌功能,如促进癌细胞增殖、增加癌症干细胞产生、促进新生血管生成等。

2.3 促进上皮-间质转化和治疗抵抗

上皮-间质转化(EMT)是癌症侵袭和转移的关键,其特点是细胞间黏附丧失,间充质标志物(N-钙黏蛋白)表达增加[35-36]。多组学分析表明,转谷氨酰胺酶(transglutaminase 2, TG2)是EMT过程必需的转录调控因子之一,HCC中CAFs通过分泌IL-6,活化下游STAT3,从而使HCC高表达TG2以促进其侵袭和转移[37]。CAFs还可以分泌趋化因子CXC12配体(CXCL12)诱导M2型巨噬细胞极化,并促进其表达纤溶酶原激活剂抑制剂 1(plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, PAI-1),最终通过EMT增加HCC的恶性程度[38]。

Liu等发现HCC患者的CAFs分泌更多趋化因子CXCL11,该因子通过circUBAP2/miR-4756/IFIT1/3轴重塑ECM来促进HCC转移,同时激活LINC 00152/miR205-5p/CXCL11轴,影响HCC细胞的体外增殖和迁移以及体内HCC细胞生长[39-40]。CAFs来源趋化因子CCL5通过激活HIF-1α/ZEB1轴促进HCC转移[41]。另外,有研究发现,血浆CAFs来源外泌体中miR-150-3p(特异性微小RNA)的表达水平与HCC患者预后正相关,CAFs外泌体缺失miR-150-3p会明显促进HCC转移[42]。HCC细胞高表达硫酸酯酶2(sulfatase-2, SULF2),诱导CAFs激活SDF-1/CXCR4/PI3K/AKT信号转导途径减弱癌细胞凋亡,并通过SDF-1/CXCR4/OIP5-AS1/miR-153-3p/SNAI1轴诱导EMT[43];而CAFs来源SULF2激活TAK1/IKKβ/NF-κB通路以调节磷脂酰肌醇蛋白聚糖-3/β-连环蛋白信号转导[44],增强癌细胞的迁移能力;CAFs旁分泌软骨寡聚基质蛋白(cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, COMP)促进EMT和癌症干细胞(cancer stem cell, CSC)增殖[45]。CAFs可以诱导HCC中内质网钙离子结合蛋白1(reticulocalbin1, RCN1)的表达,RCN1可以通过IRE1α-XBP1s通路减弱HCC细胞对索拉非尼的敏感性[46]。Eun等发现CAFs来源的分泌型磷蛋白1能够通过整合素蛋白激酶C(protein kinase C alpha, PKCα)激活MAPK/PI3K/AKT/mTOR等通路并促进EMT增强HCC对索拉非尼和仑伐替尼的耐药性[47]。上述研究均表明,CAFs不仅能形成物理屏障阻碍药物对癌细胞的直接杀伤,还能通过激活促癌信号通路和促进EMT发生,获得针对多靶点络氨酸激酶抑制剂(tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKIs)等药物的抵抗[48]。 CAFs在HCC中的起源和功能,见图1。

![]() 图 1 HCC中CAFs的起源和功能Figure 1 Origin and function of cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)CAFs mainly originate from tissue intrinsic fibroblasts, but can also be transformed from epithelial or endothelial cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. CAFs are involved in ECM remodeling, immunosuppression, neovascularization, promotion of cancer cell proliferation and metastasis, and treatment resistance. TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; IDO: indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; EndoMT: endothelial to mesenchymal transition; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ECM: extracellular matrix.

图 1 HCC中CAFs的起源和功能Figure 1 Origin and function of cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)CAFs mainly originate from tissue intrinsic fibroblasts, but can also be transformed from epithelial or endothelial cells and bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. CAFs are involved in ECM remodeling, immunosuppression, neovascularization, promotion of cancer cell proliferation and metastasis, and treatment resistance. TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-alpha; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; IDO: indoleamine 2, 3-dioxygenase; PGE2: prostaglandin E2; EndoMT: endothelial to mesenchymal transition; EMT: epithelial-mesenchymal transition; ECM: extracellular matrix.3 靶向CAFs治疗HCC的策略

CAFs在HCC的发生、进展、转移等过程中发挥了十分重要的作用,被普遍认为是有广阔前景的治疗靶点。大量消耗CAFs是最早提出的策略,然而靶向CAFs的HCC治疗开发同其他实体瘤面临相同的问题:CAFs具有异质性高、缺乏谱系特异性标志物的特点,很难在不损害正常组织的条件下精准靶向并消耗CAFs,过度破坏正常基质成分将产生极其严重的后果。由此,研究者们在精确靶向CAFs的基础上提出了一些治疗策略设想。

3.1 逆转活化CAFs的促癌表型

研究发现,胰腺导管腺癌患者缺乏维生素A会导致胰腺星状细胞(pancreatic stellate cells, PSCs)激活而获得CAFs表型,全反式维甲酸(ATRA)则能逆转该效应,使PSCs重新恢复静息状态而失去促癌表型[49]。CAFs表型逆转现象并不是胰腺癌所特有的,在小鼠模型中,当肝纤维化自发消退时,HSCs和肌成纤维细胞也可以恢复到不活跃状态,因此消除CAFs促癌表型可能是抗HCC的一条新思路。

3.2 靶向CAFs的激活信号和下游信号通路

根据目前的技术水平,相比于消耗CAFs和逆转其表型,靶向CAFs促瘤通路上的其他调控因子更易实现。靶向CAFs产生的方法主要是抑制CAFs募集、激活相关分子,通过阻断CAFs在癌细胞周围的富集和活化来抑制其功能;而阻断CAFs下游的促瘤相关信号通路也具有较高可行性,其中IL-6/STAT3作为与HCC增殖、血管生成、转移、免疫逃逸等恶性行为相关的重要通路,目前已有针对IL-6、STAT3等靶点的新型抑制剂获批进行癌症临床试验[50]。

3.3 靶向CAFs产生的细胞外基质蛋白

肿瘤通常会发生促结缔组织增生反应,即由CAFs介导纤维胶原、纤连蛋白等大量沉积生成ECM,ECM的进一步重塑及交联增加导致肿瘤外围形成免疫和药物屏障,既损害免疫细胞的浸润和杀伤作用,又引起药物治疗抵抗[51]。靶向ECM蛋白的产生或降解途径可能有利于增强免疫系统的抗癌能力,改善药物疗效,但目前还没有抗基质疗法的成功案例,可能是由于这种方法同时破坏了维持组织稳态所需的基质成分。相比于存在更多隐患的直接消耗法,再次重塑ECM使其失去或减弱促癌作用似乎更可行。

3.4 构建CAFs治疗递送体系

已有临床前研究将CAFs作为纳米药物递送媒介用于胰腺癌和膀胱癌治疗,可分泌性TNF相关凋亡诱导配体(TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, sTRAIL)质粒被封装于脂质包被的鱼精蛋白DNA复合物(liposome-protamin-DNA complex, LPD),CAFs摄取该药物后获得sTRAIL持续分泌表型,使临近的癌细胞凋亡,并阻碍其他成纤维细胞活化[52]。然而体外修饰的CAFs仍可能存在促癌作用,因此应谨慎使用[53]。

4 CAFs相关临床试验

目前,已有多项靶向CAFs治疗包括头颈鳞癌、胰腺癌、食管癌等多种实体瘤的临床试验,见表1。

表 1 靶向CAFs的癌症治疗临床试验Table 1 Clinical trials of cancer therapy targeting CAFsTarget Name Diseases Drugs Mechanism Status Interfere with the activation of CAFs FGFR JNJ-42756493 Non-small cell lung cancer

Urothelial carcinoma

Esophageal Cancer

CholangiocarcinomaSmall molecule

inhibitorInhibit the activation

of CAFsPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ

clinical trials in

progressHedgehog IPI-926 (saridegib)

and vismodegibAdvanced pancreatic cancer Small molecule

inhibitorInhibit the activation

of CAFsClinical trials in

progressInterfere with the activation and functions of CAFs TGF-β Various, including

galunisertibMetastatic cancer (Stage Ⅰb)

Advanced unresectable

pancreatic cancer (Stage Ⅱ)

Rectal adenocarcinomaBlocking antibodies

Small molecule

receptor inhibitorsInhibit the activation

of CAFs

ImmunosuppressionPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ/Ⅲ

clinical trials in

progressAngiotensin receptor Losartan Pancreatic cancer Small molecule

inhibitorReduce collagen and

hyaluronic acidPhase Ⅱ clinical

trial completed

randomized

controlled trial

in progressInterfere with the functions of CAFs CXCR4 AMD3100 Advanced pancreatic cancer

High-grade serous ovarian

cancer

Colorectal cancerSmall molecule inhibitor Inhibit the signaling

between CAFs and

immune cellsClinical trials in

progressROCK AT13148 Advanced solid tumors Small molecule

inhibitorDecrease contractility Phase Ⅰ clinical

trial completedFAK Defactinib (VS-6063, PF-04554878) Non-small cell lung cancer Small molecule

inhibitorReduce the

downstream

signaling of

integrinsClinical trials in

progressLOXL2 Simtuzumab (GS 6624) Pancreatic cancer Antibody blocker Anti-crosslinking Preclinical trials

and fibrosis

assaysCTGF FG-3019 Idiopathic pulmonary

fibrosisAntibody blocker Block antibody

binding to receptorsEarly clinical trials

are underwayHyaluronic acid PEGPH20 (PVHA) Metastatic pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinomaPolyethylene

glycolaseDegrade ECM to

enhance the efficacy

of cytotoxic therapyPhase Ⅲ clinical

trial completed,

awaiting final

analysisFAP-expressing cells Various, including PT630 and RO6874281 Head and neck cancer

Esophageal cancer

Cervical cancer

(pathologically diagnosed as

squamous cell carcinoma)Blocking antibody

(sibrotuzumab Ⅰ)

and molecular

radiotherapyInhibit FAP+ CAFs function, Enhance

T cell functionalityPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ clinical trials in progress Eliminate the pro-tumorigenic phenotype of CAFs Vitamin A metabolism ATRA Pancreatic cancer Metabolites of vitamin A Normalize stellate

cellsClinical trials in

progressVitamin D receptor Paricalcitol Pancreatic adenocarcinoma or

distant metastasis of poorly

differentiated cancerSmall molecule

receptor agonistsNormalize stellate

cellsClinical trials in

progressNotes: FGFR: fibroblast growth factor receptor; CXCR4: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; ROCK: Rho-associated protein kinase; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; LOXL2: lysyl oxidase-related protein 2; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor. 5 总结与展望

肝细胞癌微环境具有高度异质性、免疫抑制等特点,这取决于其复杂多样的形成机制。CAFs作为HCC基质中最丰富的成分,可以与癌细胞、免疫细胞、上皮/内皮细胞等互作,通过直接或间接的方式,重塑ECM、促进新生血管形成和癌细胞增殖、增强癌症干性及抑制免疫杀伤和免疫监视等[54-55],最终促进HCC发生和发展,这些过程涉及到多种因子和信号转导通路,其中IL-6、STAT3、TGF-β等[37,55-57]分子已被证明发挥了关键作用。由于HCC发生发展所涉及的机制多样,目前单一、粗放的治疗手段已经无法满足HCC患者对精准诊治的需要,尤其是中晚期患者,长期服用靶向药物会产生耐药,而免疫治疗响应率仍差强人意,CAFs作为重要的癌症治疗新靶点,目前已有多项临床试验正在开展,这些研究主要是通过小分子抑制剂、抗体阻断剂等对CAFs的产生、消除和促癌机制方面进行干预,或者与现有治疗药物联用来阻断CAFs促癌相关靶点[58-62]。受限于技术水平,对HCC中CAFs亚群的准确鉴定存在一定困难,并且靶向CAFs在HCC治疗的应用中仍存在许多不确定因素,目前早期临床试验尚缺乏成功案例。在胰腺癌治疗中,抑制FAP+CAFs的CXCL12表达已被证明与抗PD-L1免疫疗法存在协同效应[63]。最近一项研究表明,TME中CAFs丰度较高的HCC患者在接受PD-1抑制剂和抗血管生成药物联合治疗时疗效更差[64],因此也可以考虑将CAFs靶向疗法与现有靶免方案联合使用提高整体疗效。随着研究的深入,将可能有更多安全有效的CAFs靶向疗法问世,以单药或联合治疗的方式应用于临床,降低HCC治疗失败率,进一步改善患者预后。

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。作者贡献:杨祎杰:文献查阅、绘图、文章撰写及修改王帅、徐骁:指导文章选题、构思和修改 -

表 1 靶向CAFs的癌症治疗临床试验

Table 1 Clinical trials of cancer therapy targeting CAFs

Target Name Diseases Drugs Mechanism Status Interfere with the activation of CAFs FGFR JNJ-42756493 Non-small cell lung cancer

Urothelial carcinoma

Esophageal Cancer

CholangiocarcinomaSmall molecule

inhibitorInhibit the activation

of CAFsPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ

clinical trials in

progressHedgehog IPI-926 (saridegib)

and vismodegibAdvanced pancreatic cancer Small molecule

inhibitorInhibit the activation

of CAFsClinical trials in

progressInterfere with the activation and functions of CAFs TGF-β Various, including

galunisertibMetastatic cancer (Stage Ⅰb)

Advanced unresectable

pancreatic cancer (Stage Ⅱ)

Rectal adenocarcinomaBlocking antibodies

Small molecule

receptor inhibitorsInhibit the activation

of CAFs

ImmunosuppressionPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ/Ⅲ

clinical trials in

progressAngiotensin receptor Losartan Pancreatic cancer Small molecule

inhibitorReduce collagen and

hyaluronic acidPhase Ⅱ clinical

trial completed

randomized

controlled trial

in progressInterfere with the functions of CAFs CXCR4 AMD3100 Advanced pancreatic cancer

High-grade serous ovarian

cancer

Colorectal cancerSmall molecule inhibitor Inhibit the signaling

between CAFs and

immune cellsClinical trials in

progressROCK AT13148 Advanced solid tumors Small molecule

inhibitorDecrease contractility Phase Ⅰ clinical

trial completedFAK Defactinib (VS-6063, PF-04554878) Non-small cell lung cancer Small molecule

inhibitorReduce the

downstream

signaling of

integrinsClinical trials in

progressLOXL2 Simtuzumab (GS 6624) Pancreatic cancer Antibody blocker Anti-crosslinking Preclinical trials

and fibrosis

assaysCTGF FG-3019 Idiopathic pulmonary

fibrosisAntibody blocker Block antibody

binding to receptorsEarly clinical trials

are underwayHyaluronic acid PEGPH20 (PVHA) Metastatic pancreatic ductal

adenocarcinomaPolyethylene

glycolaseDegrade ECM to

enhance the efficacy

of cytotoxic therapyPhase Ⅲ clinical

trial completed,

awaiting final

analysisFAP-expressing cells Various, including PT630 and RO6874281 Head and neck cancer

Esophageal cancer

Cervical cancer

(pathologically diagnosed as

squamous cell carcinoma)Blocking antibody

(sibrotuzumab Ⅰ)

and molecular

radiotherapyInhibit FAP+ CAFs function, Enhance

T cell functionalityPhase Ⅰ/Ⅱ clinical trials in progress Eliminate the pro-tumorigenic phenotype of CAFs Vitamin A metabolism ATRA Pancreatic cancer Metabolites of vitamin A Normalize stellate

cellsClinical trials in

progressVitamin D receptor Paricalcitol Pancreatic adenocarcinoma or

distant metastasis of poorly

differentiated cancerSmall molecule

receptor agonistsNormalize stellate

cellsClinical trials in

progressNotes: FGFR: fibroblast growth factor receptor; CXCR4: C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4; ROCK: Rho-associated protein kinase; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; LOXL2: lysyl oxidase-related protein 2; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor. -

[1] Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mor tality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249.

[2] Park JW, Chen M, Colombo M, et al. Global patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma management from diagnosis to death: the BRIDGE Study[J]. Liver Int, 2015, 35(9): 2155-2166. doi: 10.1111/liv.12818

[3] Jin MZ, Jin WL. The updated landscape of tumor microenvironment and drug repurposing[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1): 166. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00280-x

[4] Tang T, Huang X, Zhang G, et al. Advantages of targeting the tumor immune microenvironment over blocking immune checkpoint in cancer immunotherapy[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2021, 6(1): 72. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00449-4

[5] Elhanani O, Ben-Uri R, Keren L. Spatial profiling technologies illuminate the tumor microenvironment[J]. Cancer Cell, 2023, 41(3): 404-420. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.01.010

[6] Xiao Y, Yu D. Tumor microenvironment as a therapeutic target in cancer[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 221: 107753. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107753

[7] Baglieri J, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. The Role of Fibrosis and Liver-Associated Fibroblasts in the Pathogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(7): 1723. doi: 10.3390/ijms20071723

[8] Özdemir BC, Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens JL, et al. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival[J]. Cancer Cell, 2014, 25(6): 719-734. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005

[9] Bhattacharjee S, Hamberger F, Ravichandra A, et al. Tumor restriction by type I collagen opposes tumor-promoting effects of cancer-associated fibroblasts[J]. J Clin Invest, 2021, 131(11): e146987. doi: 10.1172/JCI146987

[10] Biffi G, Tuveson DA. Diversity and Biology of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts[J]. Physiol Rev, 2021, 101(1): 147-176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2019

[11] Apte MV, Haber PS, Darby SJ, et al. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis[J]. Gut, 1999, 44(4): 534-541. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.534

[12] Arina A, Idel C, Hyjek EM, et al. Tumor-associated fibroblasts predominantly come from local and not circulating precursors[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016, 113(27): 7551-7556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600363113

[13] Mizutani Y, Kobayashi H, Iida T, et al. Meflin-Positive Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Inhibit Pancreatic Carcinogenesis[J]. Cancer Res, 2019, 79(20): 5367-5381. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-0454

[14] Kobayashi H, Enomoto A, Woods SL, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastrointestinal cancer[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019, 16(5): 282-295. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0115-0

[15] Park D, Sahai E, Rullan A. SnapShot: Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts[J]. Cell, 2020, 181(2) 181: 486-486. e1.

[16] Cogliati B, Yashaswini CN, Wang S, et al. Friend or foe? The elusive role of hepatic stellate cells in liver cancer[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023, 20(10): 647-661. doi: 10.1038/s41575-023-00821-z

[17] Wei L, Ye H, Li G, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote progression and gemcitabine resistance via the SDF-1/SATB-1 pathway in pancreatic cancer[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9(11): 1065. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-1104-x

[18] Qin X, Yan M, Wang X, et al. Cancer-associated Fibroblast-derived IL-6 Promotes Head and Neck Cancer Progression via the Osteopontin-NF-kappa B Signaling Pathway[J]. Theranostics, 2018, 8(4): 921-940. doi: 10.7150/thno.22182

[19] Kubo N, Araki K, Kuwano H, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2016, 22(30): 6841-6850. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i30.6841

[20] Givel AM, Kieffer Y, Scholer-Dahirel A, et al. miR200-regulated CXCL12β promotes fibroblast heterogeneity and immunosuppression in ovarian cancers[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 1056. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03348-z

[21] Shalapour S, Lin XJ, Bastian IN, et al. Inflammation-induced IgA+ cells dismantle anti-liver cancer immunity[J]. Nature, 2017, 551(7680): 340-345. doi: 10.1038/nature24302

[22] Curtis M, Kenny HA, Ashcroft B, et al. Fibroblasts Mobilize Tumor Cell Glycogen to Promote Proliferation and Metastasis[J]. Cell Metab, 2019, 29(1): 141-155. e9.

[23] Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, et al. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma[J]. Cell Cycle, 2009, 8(23): 3984-4001. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238

[24] Fang M, Yuan J, Chen M, et al. The heterogenic tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma and prognostic analysis based on tumor neo-vessels, macrophages and α-SMA[J]. Oncol Lett, 2018, 15(4): 4805-4812.

[25] Jia CC, Wang TT, Liu W, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts from hepatocellular carcinoma promote malignant cell proliferation by HGF secretion[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(5): e63243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063243

[26] Liu Y, Xun Z, Ma K, et al. Identification of a tumour immune barrier in the HCC microenvironment that determines the efficacy of immunotherapy[J]. J Hepatol, 2023, 78(4): 770-782. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.01.011

[27] Zhu GQ, Tang Z, Huang R, et al. CD36+ cancer-associated fibroblasts provide immunosuppressive microenvironment for hepatocellular carcinoma via secretion of macrophage migration inhibitory factor[J]. Cell Discov, 2023, 9(1): 25. doi: 10.1038/s41421-023-00529-z

[28] Cheng Y, Li H, Deng Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce PDL1+ neutrophils through the IL6-STAT3 pathway that foster immune suppression in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9(4): 422. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0458-4

[29] Li T, Yang Y, Hua X, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma-associated fibroblasts trigger NK cell dysfunction via PGE2 and IDO[J]. Cancer Lett, 2012, 318(2): 154-161. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.12.020

[30] Zhao J, Li R, Li J, et al. CAFs-derived SCUBE1 promotes malignancy and stemness through the Shh/Gli1 pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. J Transl Med, 2022, 20(1): 520. doi: 10.1186/s12967-022-03689-w

[31] Wu J, Tan HY, Chan YT, et al. PARD3 drives tumorigenesis through activating Sonic Hedgehog signalling in tumour-initiating cells in liver cancer[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2024, 43(1): 42. doi: 10.1186/s13046-024-02967-3

[32] Song M, He J, Pan QZ, et al. Cancer-Associated Fibroblast-Mediated Cellular Crosstalk Supports Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression[J]. Hepatology, 2021, 73(5): 1717-1735. doi: 10.1002/hep.31792

[33] Huang MD, Chen WM, Qi FZ, et al. Long non-coding RNA TUG1 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes cell growth and apoptosis by epigenetically silencing of KLF2[J]. Mol Cancer, 2015, 14: 165. doi: 10.1186/s12943-015-0431-0

[34] Lu L, Huang J, Mo J, et al. Exosomal lncRNA TUG1 from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes liver cancer cell migration, invasion, and glycolysis by regulating the miR-524-5p/SIX1 axis[J]. Cell Mol Biol Lett, 2022, 27(1): 17. doi: 10.1186/s11658-022-00309-9

[35] Wang H, Rao B, Lou J, et al. The Function of the HGF/c-Met Axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2020, 8: 55. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00055

[36] Alqurashi YE, Al-Hetty H, Ramaiah P, et al. Harnessing function of EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma: From biological view to nanotechnological standpoint[J]. Environ Res, 2023, 227: 115683. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.115683

[37] Jia C, Wang G, Wang T, et al. Cancer-associated Fibroblasts induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the Transglutaminase 2-dependent IL-6/IL6R/STAT3 axis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2020, 16(14): 2542-2558. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45446

[38] Chen S, Morine Y, Tokuda K, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-induced M2-polarized macrophages promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression via the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 pathway[J]. Int J Oncol, 2021, 59(2): 59. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2021.5239

[39] Liu G, Sun J, Yang ZF, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived CXCL11 modulates hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration and tumor metastasis through the circUBAP2/miR-4756/IFIT1/3 axis[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2021, 12(3): 260. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03545-7

[40] Liu G, Yang ZF, Sun J, et al. The LINC00152/miR-205-5p/CXCL11 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma cancer-associated fibroblasts affects cancer cell phenotypes and tumor growth[J]. Cell Oncol(Dordr), 2022, 45(6): 1435-1449. doi: 10.1007/s13402-022-00730-4

[41] Xu H, Zhao J, Li J, et al. Cancer associated fibroblast-derived CCL5 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through activating HIF1α/ZEB1 axis[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2022, 13(5): 478. doi: 10.1038/s41419-022-04935-1

[42] Yugawa K, Yoshizumi T, Mano Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote hepatocellular carcinoma progression through downregulation of exosomal miR-150-3p[J]. Eur J Surg Oncol, 2021, 47(2): 384-393. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2020.08.002

[43] Wang C, Shang C, Gai X, et al. Sulfatase 2-Induced Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Promote Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression via Inhibition of Apoptosis and Induction of Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2021, 9: 631931. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.631931

[44] Zaki MYW, Alhasan SF, Shukla R, et al. Sulfatase-2 from Cancer Associated Fibroblasts: An Environmental Target for Hepatocellular Carcinoma?[J]. Liver Cancer, 2022, 11(6): 540-557. doi: 10.1159/000525375

[45] Sun L, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. Resolvin D1 prevents epithelial-mesenchymal transition and reduces the stemness features of hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting paracrine of cancer-associated fibroblast-derived COMP[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 38(1): 170. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1163-6

[46] Taura K, Miura K, Iwaisako K, et al. Hepatocytes do not undergo epithelial-mesenchymal transition in liver fibrosis in mice[J]. Hepatology, 2010, 51(3): 1027-1036. doi: 10.1002/hep.23368

[47] Eun JW, Yoon JH, Ahn HR, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived secreted phosphoprotein 1 contributes to resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to sorafenib and lenvatinib[J]. Cancer Commun (Lond), 2023, 43(4): 455-479. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12414

[48] Gao L, Morine Y, Yamada S, et al. The BAFF/NFκB axis is crucial to interactions between sorafenib-resistant HCC cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts[J]. Cancer Sci, 2021, 112(9): 3545-3554. doi: 10.1111/cas.15041

[49] Froeling FE, Feig C, Chelala C, et al. Retinoic acid-induced pancreatic stellate cell quiescence reduces paracrine Wnt-β-catenin signaling to slow tumor progression[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 141(4): 1486-1497, 1497. e1-14.

[50] Johnson DE, O'Keefe RA, Grandis JR. Targeting the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signalling axis in cancer[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018, 15(4): 234-248. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.8

[51] Rønnov-Jessen L, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Cellular changes involved in conversion of normal to malignant breast: importance of the stromal reaction[J]. Physiol Rev, 1996, 76(1): 69-125. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.1.69

[52] Miao L, Liu Q, Lin CM, et al. Targeting Tumor-Associated Fibroblasts for Therapeutic Delivery in Desmoplastic Tumors[J]. Cancer Res, 2017, 77(3): 719-731. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0866

[53] Kaps L, Schuppan D. Targeting Cancer Associated Fibroblasts in Liver Fibrosis and Liver Cancer Using Nanocarriers[J]. Cells, 2020, 9(9): 2027. doi: 10.3390/cells9092027

[54] Zhang J, Gu C, Song Q, et al. Identifying cancer-associated fibroblasts as emerging targets for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cell Biosci, 2020, 10(1): 127. doi: 10.1186/s13578-020-00488-y

[55] Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2014, 147(6): 1393-1404. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039

[56] Dituri F, Mancarella S, Cigliano A, et al. TGF-β as Multifaceted Orchestrator in HCC Progression: Signaling, EMT, Immune Microenvironment, and Novel Therapeutic Perspectives[J]. Semin Liver Dis, 2019, 39(1): 53-69. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676121

[57] Soukupova J, Malfettone A, Bertran E, et al. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) Induced by TGF-β in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells Reprograms Lipid Metabolism[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(11): 5543. doi: 10.3390/ijms22115543

[58] Pietrobono S, Sabbadini F, Bertolini M, et al. Autotaxin Secretion Is a Stromal Mechanism of Adaptive Resistance to TGFβ Inhibition in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma[J]. Cancer Res, 2024, 84(1): 118-132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0104

[59] No authors listed. FAP-Targeted 4-1BB Agonist Tamps Down Advanced Tumors[J]. Cancer Discov, 2023, 13(8): OF2. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2023-0044

[60] Goyal L, Meric-Bernstam F, Hollebecque A, et al. Futibatinib for FGFR2-Rearranged Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2023, 388(3): 228-239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2206834

[61] Lassman AB, Sepúlveda-Sánchez JM, Cloughesy TF, et al. Infigratinib in Patients with Recurrent Gliomas and FGFR Alterations: A Multicenter Phase Ⅱ Study[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2022, 28(11): 2270-2277. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2664

[62] Subbiah V, Iannotti NO, Gutierrez M, et al. FIGHT-101, a first-in-human study of potent and selective FGFR 1-3 inhibitor pemigatinib in pan-cancer patients with FGF/FGFR alterations and advanced malignancies[J]. Ann Oncol, 2022, 33(5): 522-533. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.02.001

[63] Feig C, Jones JO, Kraman M, et al. Targeting CXCL12 from FAP-expressing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts synergizes with anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013, 110(50): 20212-20217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320318110

[64] Chen Q, Wang X, Zheng Y, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts contribute to the immunosuppressive landscape and influence the efficacy of the combination therapy of PD-1 inhibitors and antiangiogenic agents in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Cancer, 2023, 129(21): 3405-3416. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34935

-

期刊类型引用(1)

1. 卢美希,姜润秋. 肝癌相关成纤维细胞中FXR和TGR5表达与T细胞浸润及预后的相关性分析. 江苏大学学报(医学版). 2025(02): 139-144+153 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

徐骁: 教育部“长江学者奖励计划”特聘教授,国家杰出青年科学基金获得者,“万人计划”科技创新领军人才,国家重点研发计划“干细胞研究与器官修复”项目首席科学家,浙江大学求是特聘教授、主任医师、博士生导师,浙江省肿瘤融合研究与智能医学重点实验室主任。现任中华医学会器官移植学分会候任主任委员兼肝移植学组组长、中国医师协会器官移植医师分会副会长兼总干事、国家肝脏移植质控中心副主任、国家人体捐献器官获取质控中心副主任、中国抗癌协会肿瘤精准治疗专业委员会副主任委员、中国抗癌协会肿瘤转移专业委员会副主任委员、浙江省抗癌协会肿瘤精准诊治专业委员会主任委员、浙江省医学会器官移植学分会候任主任委员等。 长期从事肝胆胰外科、肝移植临床和教学工作,致力于移植肿瘤学、器官修复与再生医学研究。主持国家科技重大专项、重点研发计划及国家自然科学基金重点项目等。以通信作者或第一作者身份在Gut、Hepatology等学术期刊发表SCI论文240余篇。主编、主译或参编《器官移植学名词》《器官移植学》《临床医学导论》及《外科学》等多部国家级规划教材和专著,作为第一完成人荣获浙江省科学技术进步一等奖、中华医学科学技术二等奖和浙江省教师教学创新大赛特等奖,并作为主要完成人之一多次荣获国家科技进步创新团队奖、一等奖及二等奖,中国肿瘤青年科学家奖、吴孟超医学青年基金奖和“第四届国之名医优秀风范”获得者

。

徐骁: 教育部“长江学者奖励计划”特聘教授,国家杰出青年科学基金获得者,“万人计划”科技创新领军人才,国家重点研发计划“干细胞研究与器官修复”项目首席科学家,浙江大学求是特聘教授、主任医师、博士生导师,浙江省肿瘤融合研究与智能医学重点实验室主任。现任中华医学会器官移植学分会候任主任委员兼肝移植学组组长、中国医师协会器官移植医师分会副会长兼总干事、国家肝脏移植质控中心副主任、国家人体捐献器官获取质控中心副主任、中国抗癌协会肿瘤精准治疗专业委员会副主任委员、中国抗癌协会肿瘤转移专业委员会副主任委员、浙江省抗癌协会肿瘤精准诊治专业委员会主任委员、浙江省医学会器官移植学分会候任主任委员等。 长期从事肝胆胰外科、肝移植临床和教学工作,致力于移植肿瘤学、器官修复与再生医学研究。主持国家科技重大专项、重点研发计划及国家自然科学基金重点项目等。以通信作者或第一作者身份在Gut、Hepatology等学术期刊发表SCI论文240余篇。主编、主译或参编《器官移植学名词》《器官移植学》《临床医学导论》及《外科学》等多部国家级规划教材和专著,作为第一完成人荣获浙江省科学技术进步一等奖、中华医学科学技术二等奖和浙江省教师教学创新大赛特等奖,并作为主要完成人之一多次荣获国家科技进步创新团队奖、一等奖及二等奖,中国肿瘤青年科学家奖、吴孟超医学青年基金奖和“第四届国之名医优秀风范”获得者

。

下载:

下载: