Influencing Factors of Overall Survival of Elderly Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Construction of Prediction Model of Prognosis Nomogram: A Population-Based Study

-

摘要:目的

探讨影响老年(≥60岁)肝细胞癌(HCC)患者总生存期(OS)的独立危险因素并构建列线图预测模型。

方法从SEER数据库下载2005—2020年所有老年HCC患者的临床数据。根据纳排标准,将筛选后的患者随机分为训练组(70%)和验证组(30%),单因素和多因素Cox回归分析确定老年HCC患者独立危险因素并用Kaplan-Meier生存分析进一步验证。基于确定的变量,开发并验证列线图,以预测老年HCC患者6、12和24个月的OS。使用一致性指数(C指数)、校准曲线、受试者工作特征(ROC)曲线和曲线下面积(AUC)来评价预测模型的预测效率和区分能力,采用决策曲线分析(DCA)评估列线图的临床潜在应用价值。

结果本研究最终纳入

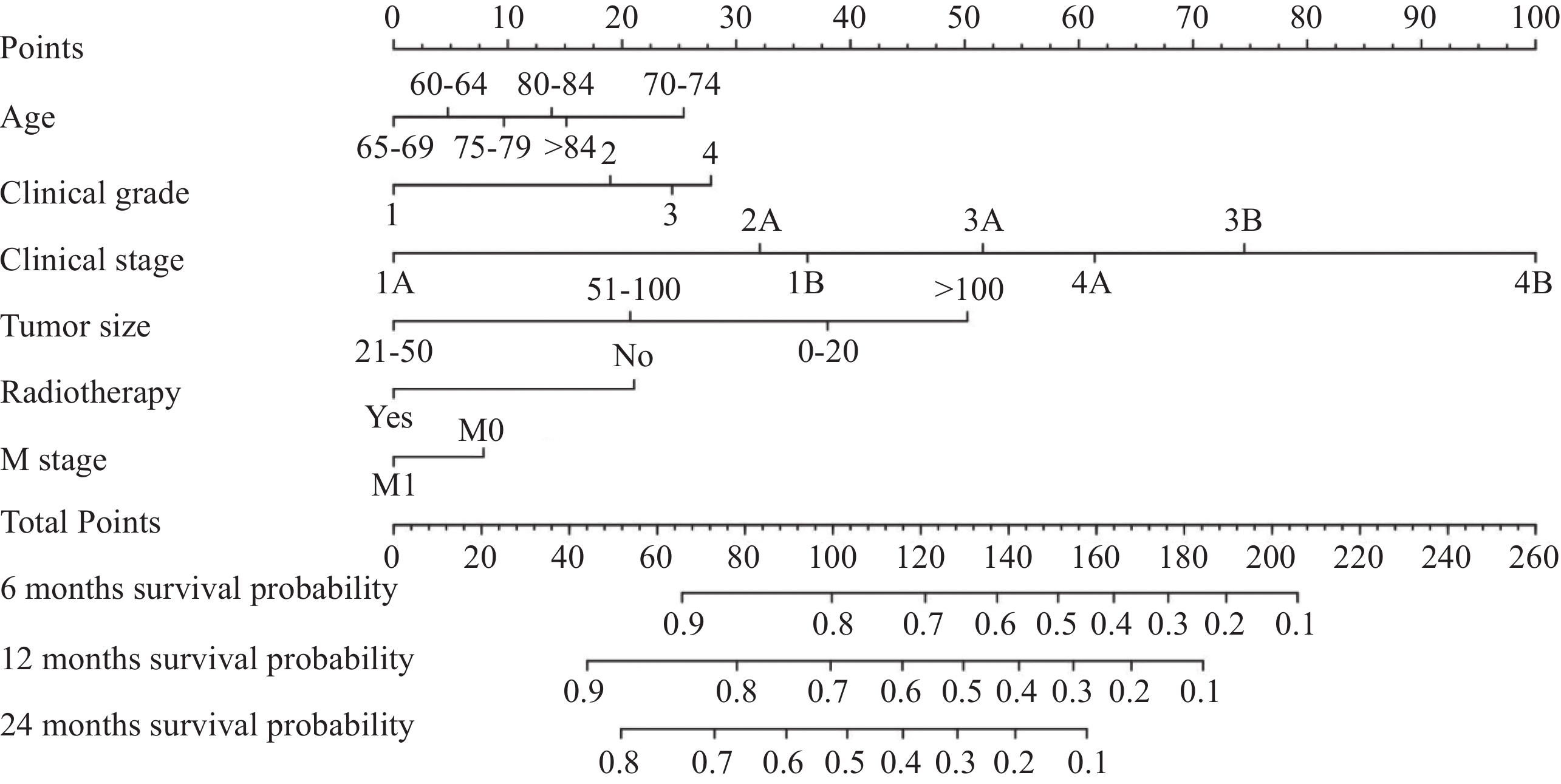

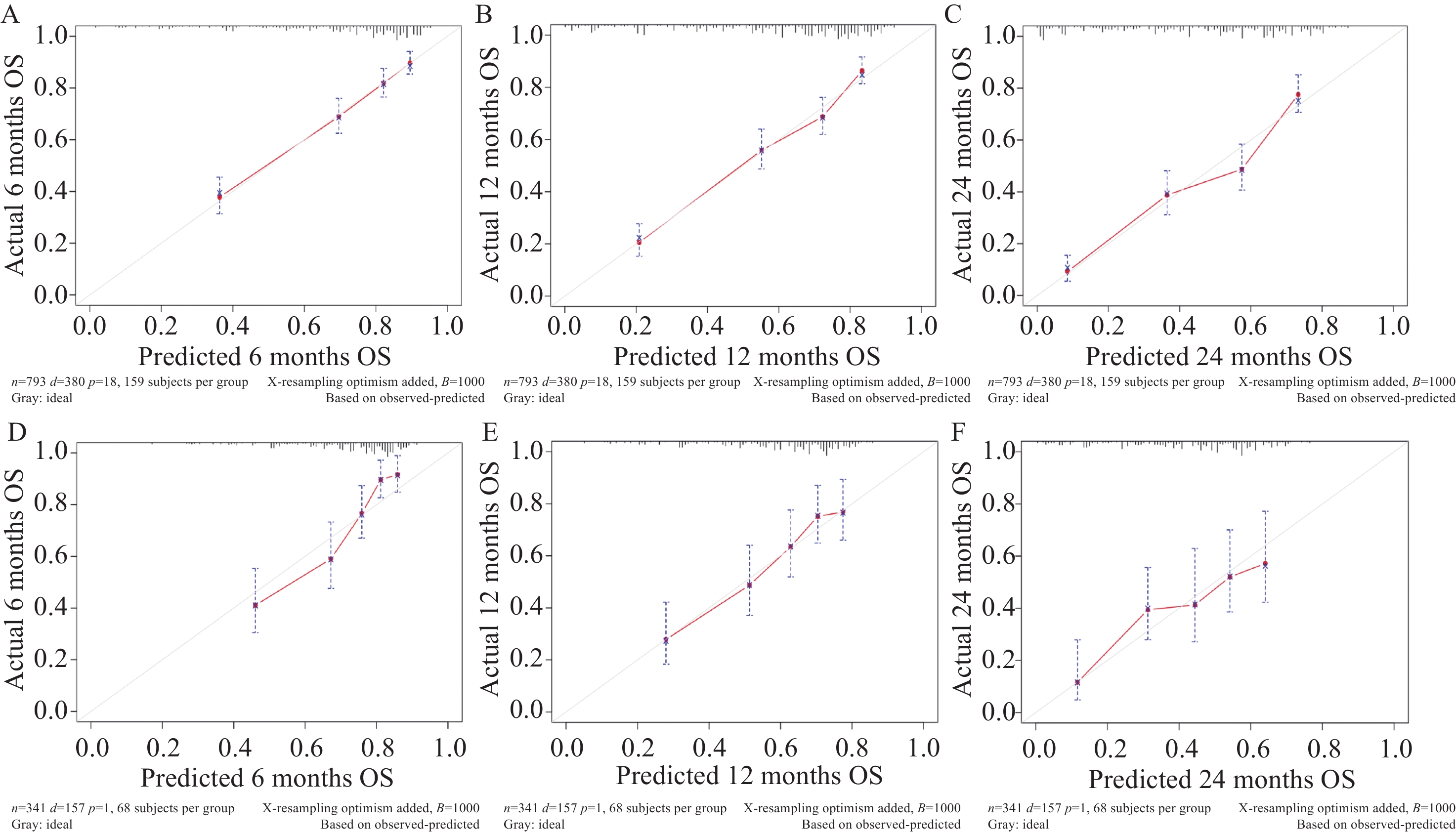

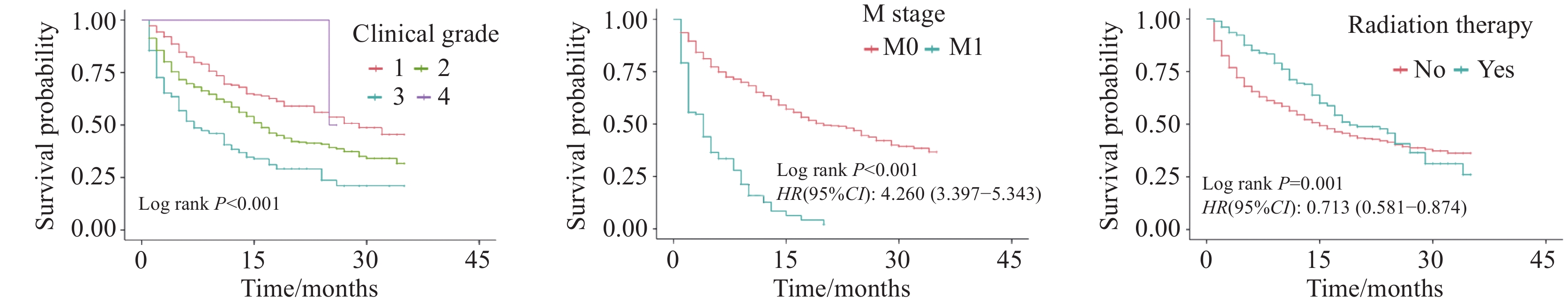

1134 例老年HCC患者,训练组793例,验证组341例。年龄、临床分级、临床分期、M分期、肿瘤大小分型和放射治疗被确定为该人群的独立预后因素。构建出的列线图表现出优异的预测性能,训练组的C指数为0.745,验证组的C指数为0.704。训练组在6、12和24个月时的AUC值分别为0.785、0.788和0.798,验证组分别为0.780、0.725和0.607。从预测的生存概率到实际观测,校准曲线表现出良好的一致性。ROC曲线和DCA显示本研究提出的列线图具有较好的预测能力。结论年龄、临床分级、临床分期、M分期、肿瘤大小分型和放疗情况均是老年HCC患者生存的重要影响因素。本研究构建的预后列线图预测模型具有良好的预测价值,可用于预测老年HCC患者OS,这将有助于老年HCC患者的个性化生存评估和临床管理。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo explore the independent risk factors that affect the overall survival (OS) of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC, ≥60 years old) and build a nomogram prediction model.

MethodsClinical data of all elderly patients with HCC from the SEER database from 2005 to 2020 were downloaded from SEER database. In accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the screened patients were randomly assigned to a training group (70%) and a validation group (30%). The independent risk factors of elderly patients with HCC were determined by univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses and further validated by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. On the basis of the determined variables, nomograms were developed and verified to predict the OS of elderly patients with HCC at 6, 12, and 24 months. The consistency index (C index), calibration curve, receiver’s operating characteristic (ROC) curve, and area under curve (AUC) were used to evaluate the prediction efficiency and discrimination ability of the prediction model, and decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the potential clinical application value of the nomogram.

ResultsA total of

1134 elderly patients with HCC were included, with 793 in the training group and 341 in the validation group. Seven variables, including age, clinical grade, clinical stage, M stage, tumor size classification, and radiotherapy, were identified as independent prognostic factors of this population. The constructed nomogram shows excellent prediction performance, with C indices of 0.745 in the training group and 0.704 in the validation group. The AUC values of the training group at 6, 12, and 24 months were 0.785, 0.788, and 0.798, respectively, and those of the validation group were 0.780, 0.725, and 0.607, respectively. The calibration curve shows good consistency from the predicted survival probability to the actual probability. The ROC curve and DCA show that the nomogram proposed in this study has good prediction ability.ConclusionAge, clinical grade, clinical stage, M stage, tumor size classification, and radiotherapy are important influencing factors for the survival of elderly patients with HCC. The prediction model of prognosis nomogram constructed in this study has good predictive value, and it can be used to predict the OS of elderly patients with HCC, which could be helpful for individualized survival assessment and clinical management of these patients.

-

Key words:

- Hepatocellular carcinoma /

- SEER database /

- Elderly /

- Prognostic factors /

- Nomogram

-

乳腺癌在我国女性恶性肿瘤中发病率位居首位,严重威胁了妇女身心健康。目前,乳腺癌的发病机制尚未明了。可能影响乳腺癌发生与发展的因素主要包括:遗传易感性、女性内源性激素不平衡、致癌基因以及多种外部环境因素等。临床治疗乳腺癌的最佳方案则是尽快尽早手术,术后再辅助化疗形成综合治疗模式。但化疗药物在杀灭癌细胞的同时也会杀灭部分正常细胞,为患者消化道、神经系统带来一些不良反应,降低了患者机体的免疫功能、生存质量以及依从性,影响预期疗效。如果利用药物辅助恶性肿瘤术后放化疗,可有效减轻化疗过程中的不良反应,有效降低肿瘤的复发率与转移率。

《乳腺癌化疗王晓稼2017观点》由王晓稼主编,科技文献出版社于2017年5月出版。本书的编写是以问题为导向,突出临床实践中的主要问题或需要解决的难点,帮助肿瘤内科医师深入理解乳腺癌分子分型指导下个体化治疗策略的精髓,如准确判断预后、充分遵循指南、理性决策诊治、合理选择方案、认真权衡利弊、兼顾患者意愿等。全书共分为五章,是中国医学临床百家丛书系列之一。书中针对我国乳腺癌的发病现状、诊疗情况与发展趋势,各级肿瘤专科医师应强化乳腺癌规范化诊疗行为,同时提高民众对乳腺癌的认知水平,尤其要对高危人群进行定期B超、钼靶等筛查,争取早期发现,从而改善乳腺癌诊断和治疗现状。乳腺癌术后辅助治疗是乳腺癌综合治疗的重要手段之一,特别是当乳腺癌治疗进入分子分型时代,其一经确诊,通过基因分型检测,明确所属亚型,并选择针对性治疗方案(化疗、内分泌治疗、靶向治疗等),即可显著延长患者生存期、提高治愈率。

在《乳腺癌化疗王晓稼2017观点》一书中,探讨了乳核内消液辅助乳腺癌术后患者化疗的方法,而在化疗前需要保证所有患者均无放射性药物接触史、无病毒性疾病病史、无明显化疗禁忌证(如炎性反应性心血管疾病、肝脏功能损伤)。在化疗过程中主要采用到了CEF方案(氟尿嘧啶+环磷酰胺+表柔比沙星),采用静脉滴注射方式连续化疗治疗21天(一个疗程),共3个疗程。疗程中主要观察患者在化疗治疗后的不良反应以及生存质量变化。其中对不良反应进行了分级,分别为Ⅱ~Ⅳ。同时采用欧洲癌症研究治疗组织所研制的EORTC生命质量测定量表,其中包括了6项功能量表以及9项症状量表,全面详细对化疗治疗后患者实施生命质量测评,主要调查了患者在化疗过程中的躯体功能、认知功能、角色功能、情绪功能以及社会功能变化。另外对患者的在化疗治疗后的疲劳、恶心呕吐以及疼痛三项症状进行了分析。该书还探讨了乳核内消液辅助乳腺癌手术以及化疗治疗后患者的不良反应影响类型,其中包括了消化系统、血液系统、皮肤黏膜、神经系统、心脏以及生殖系统毒性,分别结合上述三项症状进行评估,由此间接评价患者的生存质量。在该书中也整理大量医师观点、收集资料、希望结合临床实践,归纳总结经验,提出一些具有代表性的诊疗见解。

《乳腺癌化疗王晓稼2017观点》一书肯定了乳核内消液对乳腺癌手术患者化疗效果的辅助作用。例如采用环丙沙星、环磷酰胺、蒽环类等等作为化疗药物对乳腺癌患者的骨髓造血功能抑制、胃肠道反应以及肝脏功能损伤等方面都产生了较为严重的不良反应,而乳核内消液中涵盖了芍药、郁金香、甘草、当归等中药,它们都具有软坚散结、疏肝活血的功效,能有效为患者活血止血,缓解化疗对患者造血系统所产生的微环境损害。书中还探讨了乳核内消液在辅助乳腺癌手术后患者化疗方面的价值,发现它能够促进患者孕激素恢复正常水平,调节患者体内激素水平,提高机体免疫能力,在化疗不良反应与生存质量等方面都有正向影响。而在临床疗效确定方面,乳核内消液也能减轻患者化疗药物带来的不良反应,提高患者整体生存质量,大幅度改善远期预后。

综上所述,《乳腺癌化疗王晓稼2017观点》是具有极高的学习参考价值的,非常推荐业内相关专业人士交流阅读。

新冠病毒杀死肿瘤细胞,案例能复制吗?

日前,一篇发表在《英国血液学杂志》(British Journal of Haematology)、仅有3个段落的案例报告,震惊了世界——一位恶性淋巴瘤患者感染新冠病毒后,体内的肿瘤在未给予激素治疗、化疗、免疫治疗的情况下大面积消失。

来自英国康沃尔皇家医院血液科的作者推测,该例患者在感染新冠病毒后肿瘤神奇消失的原因可能有两种:一是病原体特异性T细胞与肿瘤抗原的反应,二是炎症细胞因子对自然杀伤细胞的激活。即新冠病毒可能从特异性免疫和广谱免疫两个方面激活了人体自身的免疫功能。

这一现象具体的发生机制,不同学者持有不同观点。有学者表示,这例个案可能仅仅是个巧合,而巧合的点很有可能与“小段肽”有关。新冠病毒蛋白外壳上的小段肽或者细胞感染后释放的小段肽,如果正好和肿瘤细胞表面的抗原相似,前者激发获得性免疫产生的杀伤性T细胞就能够识别后者。这就意味着T细胞经过新冠病毒的“介绍”认出了肿瘤细胞,从而特异性杀伤肿瘤组织。这个过程正是人体内的特异性免疫。“但这只是推测,一切要看研究团队的进一步分析。”该学者表示,但从新冠肺炎患者的表现看,这种推论是很有可能的,因为重症患者中“炎性细胞因子风暴的发生”是主要死因,这意味着新冠病毒会诱发体内免疫系统“疯狂”释放炎性因子,造成巨大杀伤力,因此只要“认得准”,完全有可能在4月内杀死患者体内的恶性肿瘤。

“根据目前的情况,我个人判断新冠病毒在这个患者体内激活的是广谱免疫。”上海海洋大学特聘教授、比昂生物创始人杨光华表示,该文中提到大幅减少的不止是肿瘤细胞,还有患者此前感染的EB病毒的数量,因此很可能新冠病毒激活了患者的整体免疫系统,使得包括自然杀伤细胞等在内的免疫细胞数量剧增,把所有其识别为“异己”的细胞或分子等统统杀死。

“目前的简单报道透露的信息较少,难以做出全面判断,也不排除特异性免疫的可能。”杨光华说。(来源:科技日报)

研究揭示肿瘤复发的关键新机制

近日,上海交通大学附属第一人民医院王传贵实验室在Nature Communications在线发表文章“The ATM and ATR kinases regulate centrosome clustering and tumor recurrence by targeting KIFC1 phosphorylation”,揭示了多类型肿瘤的复发机制,并提出新的干预策略。

该研究发现,在多类型肿瘤中,诱导DNA损伤的放疗和多种化疗药物在杀伤其他肿瘤细胞的同时,反而促进Centrosome-Clustering,导致具有多余中心体的肿瘤细胞更容易存活。因为这部分细胞可不断积累基因组不稳定性,增加肿瘤恶化、侵袭的概率,作者认为其是肿瘤复发的“种子细胞”。临床研究也发现,Centrosome-Clustering中关键蛋白KIFC1与乳腺癌、结肠癌的复发率显著正相关,与患者总生存期显著负相关;分子研究发现,DNA损伤时ATM和ATR可直接结合KIFC1,并磷酸化其第26位丝氨酸,从而促进KIFC1蛋白稳定性,导致其蛋白量显著积累,促进Centrosome-Clustering的发生;他们利用模拟KIFC1-Ser26磷酸化和去磷酸化突变体的稳转细胞株,确定Ser26的磷酸化可导致肿瘤基因组不稳定性显著增加,并增加三阴性乳腺癌复发率。而Ser26去磷化显著降低肿瘤基因组不稳定性,减少肿瘤的复发。最终,利用磷酸化抑制剂VE-822与化疗药物的联用,显著降低了小鼠模型中三阴性乳腺癌的复发率。

该研究确定了KIFC1是肿瘤复发的潜在标志物,并揭示了肿瘤复发过程中的一类“种子细胞”,从而提出新的干预策略降低肿瘤复发率。(来源:中国生物技术网)

单细胞测序揭示溶瘤病毒疗法介导的抗肿瘤反应

瑞士苏黎世大学Reinhard Dummer研究组揭示溶瘤病毒疗法介导的抗肿瘤反应。研究成果于2021年1月21日发表在《癌细胞》杂志上,题为“Oncolytic virotherapy-mediated anti-tumor response a single-cell perspective”。

研究者表示,Talimogene laherparepvec(T-VEC)是一种经基因修饰的单纯疱疹病毒1(HSV-1),已批准用于癌症治疗。他们在原发性皮肤B细胞淋巴瘤(pCBCL)中研究了注射该病毒对临床、组织学、单细胞转录组学和免疫组化水平的影响。13例患者接受病灶内T-VEC,其中11例在注射病灶中显示出肿瘤反应。通过单细胞测序,研究人员确定了恶性人群并分离了三种pCBCL亚型。

注射后24h,在注射部位的恶性和非恶性细胞中检测到HSV-1 T-VEC转录本,但未注射部位则没有。溶瘤病毒疗法可迅速根除恶性细胞。它还导致干扰素途径活化和天然杀伤细胞、单核细胞和树突状细胞的早期汇集。这些事件之后,细胞毒性T细胞发生富集,并且调节性T细胞减少。(来源:科学网)

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。作者贡献:伍 杨:软件分析、文章撰写与修改李甜、史婷婷、朱玲玲:收集整理数据张亚妮、郭佩佩、张润兵:检索文献王顺娜、高春:文章校对与修改于晓辉、张久聪:指导写作、提供基金支持 -

表 1 老年肝细胞癌患者训练组和验证组的临床病理特征[n (%)]

Table 1 Clinicopathological characteristics of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in training set and validation set (n (%))

Total (n= 1134 )Training set (n=793) Validation set (n=341) χ2 P Age(years) 11.916 0.036 60-64 254(22.4) 162(20.43) 92(26.98) 65-69 274(24.16) 205(25.85) 69(20.23) 70-74 243(21.43) 168(21.19) 75(21.99) 75-79 169(14.9) 125(15.76) 44(12.90) 80-84 118(10.41) 86(10.84) 32(9.38) >84 76(6.7) 47(5.93) 29(8.50) Ethnicity 0.057 0.972 Black 135(11.9) 95(11.98) 40(11.73) White 836(73.72) 583(73.52) 253(74.19) Others 163(14.37) 115(14.50) 48(14.08) Gender 0.821 0.365 Female 276(24.34) 187(23.58) 89(26.10) Male 858(75.66) 606(76.42) 252(73.90) Single status 0.240 0.624 No 656(57.85) 455(57.38) 201(58.94) Yes 478(42.15) 338(42.62) 140(41.06) Clinical grade − 0.847 Ⅰ 323(28.48) 227(28.63) 96(28.15) Ⅱ 614(54.14) 429(54.10) 185(54.25) Ⅲ 193(17.02) 135(17.02) 58(17.01) Ⅳ 4(0.35) 2(0.25) 2(0.59) Clinical stage 9.126 0.167 1A 72(6.35) 49(6.18) 23(6.74) 1B 453(39.95) 320(40.35) 133(39.00) 2A 160(14.11) 104(13.11) 56(16.42) 3A 176(15.52) 117(14.75) 59(17.30) 3B 86(7.58) 65(8.20) 21(6.16) 4A 67(5.91) 55(6.94) 12(3.52) 4B 120(10.58) 83(10.47) 37(10.85) T stage 3.099 0.377 T1 568(50.09) 401(50.57) 167(48.97) T2 188(16.58) 125(15.76) 63(18.48) T3 232(20.46) 158(19.92) 74(21.70) T4 146(12.87) 109(13.75) 37(10.85) N stage 6.148 0.046 N0 1021 (90.04)703(88.65) 318(93.26) N1 99(8.73) 80(10.09) 19(5.57) NX 14(1.23) 10(1.26) 4(1.17) M stage 0.037 0.847 M0 1014 (89.42)710(89.53) 304(89.15) M1 120(10.58) 83(10.47) 37(10.85) Tumor size(mm) 3.163 0.367 <20 73(6.44) 48(6.05) 25(7.33) 21-50 398(35.1) 275(34.68) 123(36.07) 51-100 400(35.27) 292(36.82) 108(31.67) >100 263(23.19) 178(22.45) 85(24.93) Radiotherapy 0.022 0.881 No 848(74.78) 592(74.65) 256(75.07) Yes 286(25.22) 201(25.35) 85(24.93) Chemotherapy 0.477 0.490 No 778(68.61) 549(69.23) 229(67.16) Yes 356(31.39) 244(30.77) 112(32.84) Surgery <0.001 >0.999 No 1119 (98.68)783(98.74) 336(98.53) Yes 15(1.32) 10(1.26) 5(1.47) Notes: χ2: Chi-square test; −: Fisher exact. 表 2 老年肝细胞癌患者总生存期的单因素和多因素Cox比例风险回归分析

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analyses of overall survival of elderly patients with hepatocellular carcinoma

Univariate analysis Multivariate analysis HR(95%CI) P HR(95%CI) P Age(years) 60-64 1.29(0.95-1.74) 0.106 1.11(0.81-1.52) 0.529 65-69 Ref Ref 70-74 1.56(1.16-2.09) 0.004 1.82(1.34-2.47) <0.001 75-79 1.36(0.97-1.89) 0.071 1.21(0.85-1.73) 0.286 80-84 1.25(0.87-1.80) 0.234 1.36(0.93-1.98) 0.109 >84 1.40(0.90-2.20) 0.137 1.33(0.83-2.13) 0.230 Ethnicity Black Ref White 0.95(0.70-1.28) 0.733 Others 0.73(0.49-1.09) 0.129 Gender Male Ref Female 1.04(0.82-1.31) 0.763 Single status Yes Ref No 0.91(0.74-1.11) 0.353 Clinical grade Ⅰ 0.60(0.46-0.77) <0.001 0.65(0.50-0.85) 0.002 Ⅱ Ref Ref Ⅲ 1.49(1.16-1.92) 0.002 1.17(0.89-1.53) 0.266 Ⅳ 1.02(0.25-4.11) 0.978 1.28(0.30-5.51) 0.741 Clinical stage 1A 0.98(0.60-1.62) 0.948 0.46(0.24-0.89) 0.020 1B Ref Ref 2A 0.93(0.64-1.35) 0.697 0.89(0.41-1.96) 0.774 3A 2.09(1.55-2.82) <0.001 1.90(0.99-3.66) 0.055 3B 3.13(2.23-4.41) <0.001 2.33(1.21-4.50) 0.012 4A 2.60(1.78-3.81) <0.001 2.88(1.41-5.91) 0.004 4B 5.82(4.27-7.92) <0.001 5.57(3.27-9.51) <0.001 T stage T1 Ref Ref T2 1.15(0.84-1.56) 0.385 1.03(0.52-2.05) 0.926 T3 2.18(1.70-2.81) <0.001 0.71(0.40-1.28) 0.261 T4 3.07(2.34-4.04) <0.001 0.97(0.56-1.71) 0.928 N stage N0 Ref Ref N1 2.22(1.67-2.96) <0.001 0.63(0.36-1.11) 0.110 NX 3.76(1.93-7.32) <0.001 0.76(0.34-1.71) 0.510 M stage M0 Ref Ref M1 4.12(3.15-5.39) <0.001 NA(NA-NA) Tumor size(mm) <20 0.73(0.46-1.15) 0.174 1.38(0.74-2.58) 0.307 21-50 0.51(0.39-0.67) <0.001 0.62(0.46-0.83) 0.002 51-100 Ref Ref >100 2.18(1.72-2.75) <0.001 1.96(1.52-2.54) <0.001 Radiotherapy No Ref Ref Yes 0.64(0.50-0.82) <0.001 0.63(0.48-0.81) <0.001 Chemotherapy No Ref Ref Yes 0.76(0.62-0.94) 0.011 1.16(0.92-1.45) 0.207 Surgery No Ref Yes 0.30(0.08-1.22) 0.092 -

[1] Jacques F, Isabelle S, Rajesh D, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. Int J Cancer, 2015, 136(5): E359-386.

[2] Siegel RL, Millerk KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2021[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(1): 7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654

[3] Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492

[4] Brown ZJ, Tsilimigras DI, Ruff SM, et al. Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Review[J]. JAMA Surg, 2023, 158(4): 410-420. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2022.7989

[5] Biggins SW, Bambha KM, Terrault NA, et al. Projected future increase in aging hepatitis C virus-infected liver transplant candidates: a potential effect of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Liver Transpl, 2012, 18(12): 1471-1478. doi: 10.1002/lt.23551

[6] Mahmood F, Xu R, Awan MUN, et al. Transcriptomics based identification of S100A3 as the key anti-hepatitis B virus factor of 16F16[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2023, 163: 114904. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114904

[7] Brar G, Greten TF, Graubard BI, et al. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival by Etiology: A SEER-Medicare Database Analysis[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2020, 4(10): 1541-1551. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1564

[8] He XK, Lin ZH, Qian Y, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with primary liver cancer[J]. Oncotarget, 2016, 8(39): 64954-64963.

[9] Orcutt ST, Anaya DA. Liver Resection and Surgical Strategies for Management of Primary Liver Cancer[J]. Cancer Control, 2018, 25(1): 1073274817744621.

[10] Huang ZR, Li L, Huang H, et al. Value of Multimodal Data From Clinical and Sonographic Parameters in Predicting Recurrence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Curative Treatment[J]. Ultrasound Med Biol, 2023, 49(8): 1789-1797. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2023.04.001

[11] Fu CC, Wei CY, Chu CJ, et al. The outcomes and prognostic factors of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and normal serum alpha fetoprotein levels[J]. J Formos Med Assoc, 2023, 122(7): 593-602. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2022.11.006

[12] Carioli G, Malvezzi M, Bertuccio P, et al. Cancer mortality in the elderly in 11 countries worldwide, 1970–2015[J]. Ann Oncol, 2019, 30(8): 1344-1355. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz178

[13] Tong YX, Cui YK, Jiang LM, et AL. Construction, validation, and visualization of two web-based nomograms for predicting overall survival and cancer-specific survival in elderly patients with primary osseous spinal neoplasms[J]. J Oncol, 2022, 2022: 7987967.

[14] Huang ZH, Tong YX, Kong QQ. The clinical characteristics, risk classification system, and web-based nomogram for primary spinal ewing sarcoma: a large population-based cohort study[J]. Global Spine J, 2022, 13(8): 2262-2270.

[15] Wen C, Tang J, Luo H. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival for middle-aged patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Front Public Health, 2022, 10: 848716. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.848716

[16] Zheng XQ, Huang JF, Chen D, et al. Prognostic nomograms to predict overall survival and cancer-specific survival in sacrum/pelvic chondrosarcoma (SC) patients: a population-based propensity score-matched study[J]. Clin Spine Surg, 2021, 34(3): E177-E185. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000001089

[17] Liu X, He S, Yao X, et al. Development and validation of prognostic nomograms for elderly patients with osteosarcoma[J]. Int J Gen Med, 2021, 14: 5581-5591. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S331623

[18] Le Saux O, Falandry C. Toxicity of cancer therapies in older patients[J]. Curr Oncol Rep, 2018, 20(8): 64. doi: 10.1007/s11912-018-0705-y

[19] Berben L, Floris G, Kenis C, et al. Age-related remodelling of the blood immunological portrait and the local tumor immune response in patients with luminal breast cancer[J]. Clin Transl Immunology, 2020, 9(10): e1184. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1184

[20] George JT, Levine H. Stochastic modeling of tumor progression and immune evasion[J]. J Theor Biol, 2018, 458: 148-155. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2018.09.012

[21] Philips CA, Rajesh S, Nair DC, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in 2021: an exhaustive update[J]. Cureus, 2021, 13(11): e19274.

[22] Kim E, Viatour P. Hepatocellular carcinoma: old friends and new tricks[J]. Exp Mol Med, 2020, 52(12): 1898-1907. doi: 10.1038/s12276-020-00527-1

[23] Chidambaranathan-Reghupaty S, Fisher PB, Sarkar D. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): epidemiology, etiology and molecular classification[J]. Adv Cancer Res, 2021, 149: 1-61.

[24] Lurje I, Czigany Z, Bednarsch J, et al. Treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma-a multidisciplinary approach[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(6): 1465. doi: 10.3390/ijms20061465

[25] Samant H, Amiri HS, Zibari GB. Addressing the worldwide hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology, prevention and management[J]. J Gastrointest Oncol, 2021, 12(Suppl 2): S361-S373.

[26] Dasgupta P, Henshaw C, Youlden DR, et al. Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 171. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.00171

[27] McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2021, 73 Suppl 1(Suppl 1): 4-13.

[28] Urquijo-Ponce JJ, Alventosa-Mateu C, Latorre-Sánchez M, et al. Present and future of new systemic therapies for early and intermediate stages of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. World J Gastroenterol, 2024, 30(19): 2512-2522. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i19.2512

[29] Fenton SE, Burns MC, Kalyan A. Epidemiology, mutational landscape and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Chin Clin Oncol, 2021, 10(1): 2. doi: 10.21037/cco-20-162

[30] Bednarsch J, Czigany Z, Heise D, et al. Prognostic evaluation of HCC patients undergoing surgical resection: an analysis of 8 different staging systems[J]. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 2021, 406(1): 75-86. doi: 10.1007/s00423-020-02052-1

[31] Singal AG, Yarchoan M, Yopp A, et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant systemic therapy in HCC: Current status and the future[J]. Hepatol Commun, 2024, 8(6): e0430.

-

期刊类型引用(8)

1. 李艳. 阴道镜下多点活检配合宫颈管搔刮术对宫颈病变的诊断价值分析. 中国实用医药. 2025(11): 78-81 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 徐岚岚,毛焱,黄芝,吴智华,翁雷. 阴道镜下ECC在CIN及宫颈癌诊断中的应用价值. 海南医学. 2024(08): 1133-1136 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 蒋彬彬,王丽利,金建峰. 基于宫颈多点活检与宫颈管搔刮术构建并验证宫颈阳性病变的诊断模型. 中国性科学. 2024(07): 83-87 .  百度学术

百度学术

4. 郑海娜,尤志学. 子宫颈内膜刮除术检出宫颈上皮内瘤变2级及以上相关影响因素研究现状. 中国计划生育学杂志. 2023(09): 2251-2255 .  百度学术

百度学术

5. 杨世勤,刘小宝,袁萍. 子宫内膜癌诊刮与手术切除标本病检结果比较. 医学信息. 2023(20): 177-179 .  百度学术

百度学术

6. 刘维娜,谢艺溶,顾海娜,周晓. 宫颈管搔刮术联合阴道镜阴性象限活检在宫颈上皮内瘤变中的应用价值. 浙江实用医学. 2023(05): 387-390 .  百度学术

百度学术

7. 钟方梅,周遵伦,郭桂芝,李建,聂蕾. 子宫颈管搔刮术在子宫颈高级别鳞状上皮内病变及以上病变诊断中的应用. 中国临床研究. 2022(06): 788-792+796 .  百度学术

百度学术

8. 李二雷,安国倩,邓宏文,刘冬梅. 不同宫颈转化区类型对阴道镜诊断宫颈上皮内瘤变准确性的影响. 循证医学. 2022(04): 224-229 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(3)

下载:

下载: