Effects of Amarogentin on Residual Liver Cancer Stem Cells After Insufficient Thermal Ablation and Related Mechanism

-

摘要:目的

探讨苦龙胆酯苷(Amarogentin)在热消融不全的残存肝癌细胞对肝癌干细胞的影响及其作用机制。

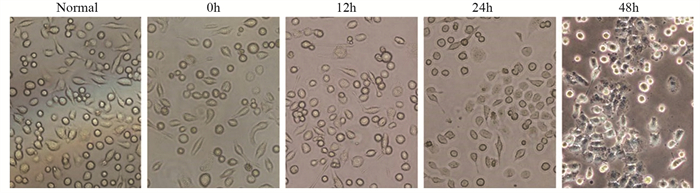

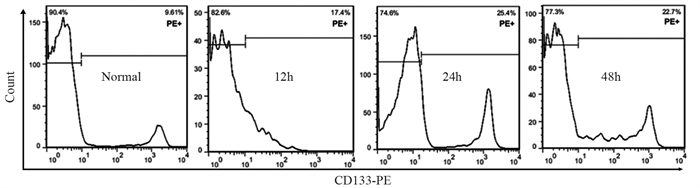

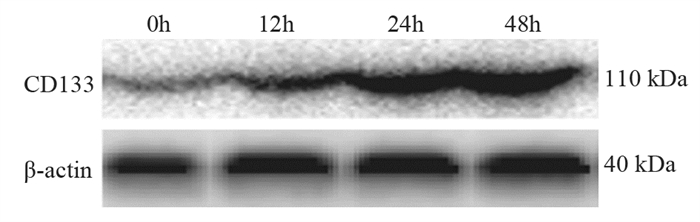

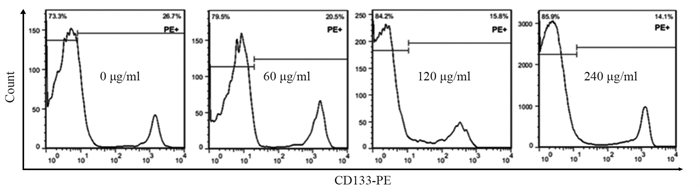

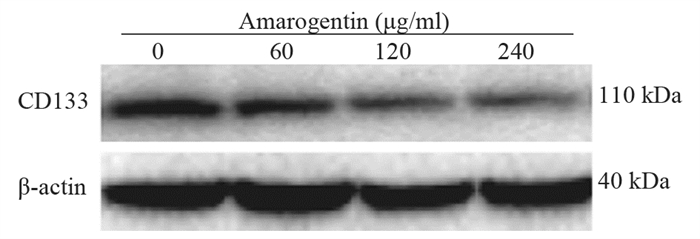

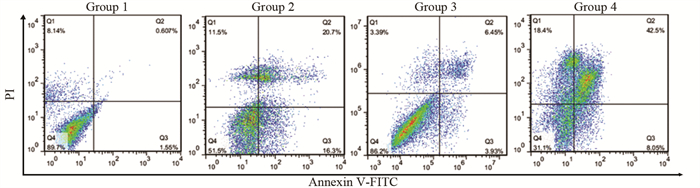

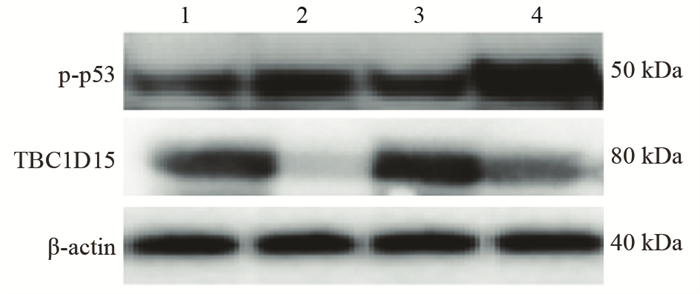

方法水浴法建立HepG2肝癌细胞热消融不全的残存模型, 流式细胞术检测细胞中CD133阳性细胞比例, qRT-PCR和Western blot法检测肝癌细胞中CD133的mRNA和蛋白的表达水平。分别用低、中和高剂量的苦龙胆酯苷处理上述HepG2细胞24 h后, 流式细胞术分别检测细胞中CD133阳性肝癌细胞比例、肝癌细胞的增殖率和凋亡率, qRT-PCR和蛋白印记法检测肝癌细胞中CD133、TBC1D15和p53的mRNA和蛋白的表达水平。

结果随培养时间的延长, 热消融不全的残存肝癌细胞中CD133阳性细胞比例、CD133和TBC1D15 mRNA和蛋白的表达水平显著提高, 而p53磷酸化水平显著下降。苦龙胆酯苷处理后, 热消融不全的残存肝癌细胞中CD133阳性细胞比例、细胞增殖率以及肿瘤干细胞相关分子CD133和TBC1D15的mRNA和蛋白表达水平显著降低(均P < 0.05);凋亡率和p53磷酸化水平提高(均P < 0.05)。

结论苦龙胆酯苷可降低热消融不全的残存肝癌干细胞的比例和肿瘤细胞的增殖, 促进细胞的凋亡, 这可能与其提高肝癌干细胞p53磷酸化和抑制TBC1D15蛋白相关。

Abstract:ObjectiveTo observe the effects of amarogentinon liver cancer stem cells (LCSCs) after insufficient thermal ablation and its mechanism.

MethodsA insufficient thermal ablation model of HepG2 cells was established by water bath method.The percentage of CD133-positive LCSCs and the mRNA and protein levels of CD133 were detected by flow cytometry, qRT-PCR and Western blot.The insufficient thermal ablation model of HepG2 cells was treated with variable doses of amarogentin for 24 h; the percentage of CD133-positive LCSCs, the proliferation and apoptosis of liver cancer cells, and the mRNA and protein levels of CD133, TBC1D15, and p53were detected by flow cytometry, qRT-PCR and Western blot.

ResultsThe percentage of CD133-positive HepG2 cells and the mRNA and protein levels of CD133 and TBC1D15in the insufficient thermal ablation model were significantly higher than those in the normal HepG2 cells.Amarogentin then markedly decreased the percentage of CD133-positive LCSCs, the proliferation rate of HepG2 cells, and the mRNA and protein levels of CD133 and TBC1D15 in the insufficient thermal ablationresidual model (all P < 0.05);inversely, the apoptosis rate of HepG2 cells and the phosphorylated levels of p53 in the insufficient thermal ablation model were significantly increased (all P < 0.05).

ConclusionAmarogentin could reduce the proportion of LCSCs after insufficient thermal ablation, inhibit the proliferation, and promote the apoptosis of LCSCs, which maybe associated with increasing the phosphorylation of p53 and inhibiting the expression of TBC1D15.

-

Key words:

- Amarogentin /

- Insufficient thermal ablation /

- Liver cancer stem cells /

- TBC1D15 /

- p53

-

0 前言

胃癌(gastric cancer, GC)每年新发病例近100万例,不仅是全球第五大最常见的癌症,同时也是第三大癌症死亡原因[1]。由于早期GC症状隐匿,仅有不到50%的确诊患者可以手术完全切除,对于姑息治疗的GC患者来说,目前预期生存时间才勉强超过1年[2]。临床评估为≥T2或有淋巴结转移的进展期GC,标准治疗策略可以是手术+术后辅助化疗或术前新辅助+手术+术后辅助。免疫治疗可以通过免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitors, ICIs)的免疫激活作用[3],增强自身免疫细胞的肿瘤杀伤能力,从而达到治疗目的,在黑色素瘤中显示出了很好的临床效益[4]。临床研究如KEYNOTE-012、ATTRACTION-2和KEYNOTE-059等支持ICIs在转移性GC患者中的疗效[5-7]。国内外的研究者均认为GC新辅助化疗(neoadjuvant chemotherapy, NACT)有效且安全,但在临床实践过程中,GC的NACT方案、剂量、周期以及是否联合治疗仍存在问题,尚需要高质量临床试验进一步验证。随着医疗水平的发展,在GC新辅助治疗中应用免疫治疗联合放化疗逐渐得到临床上的应用,目前尚未开展大型的临床试验。本文综述了免疫治疗在GC中的应用现状,同时呈现目前新辅助治疗联合免疫治疗的现状,为进一步探究GC治疗方式提供思路。

1 免疫治疗在GC中的应用

GC免疫疗法疗效初显,针对新分子的不同的联合疗法以及新的免疫疗法已经提出,但目前为止,真正对GC患者有转机作用的免疫药物尚未发现。目前的免疫治疗主要基于细胞毒性免疫细胞、单克隆抗体和基因转移疫苗[8],其中ICIs的使用迅速增长,程序性细胞死亡1(programmed cell death 1, PD-1)和程序性死亡配体1(programmed death-ligand 1, PD-L1)通路中的靶向免疫治疗是实体肿瘤管理的突破[9]。

帕博利珠单抗(pembrolizumab)作为一种抗PD-1单抗已被美国食品和药物管理局批准用于治疗局部晚期或者复发性的胃腺癌患者。然而在KEYNOTE-061试验中[10],pembrolizumab在二线治疗中的疗效没有超过紫杉醇,而且pembrolizumab联合化疗(FP、顺铂和氟尿嘧啶)在PD-L1联合阳性评分CPS为1的晚期GC/GEJ一线治疗中没有延长患者总生存期(overall survival, OS)或无进展生存期(progress free survival, PFS)[11]。

另一种抗PD-1单抗——纳武利尤单抗(nivolumab),在Attraction04试验中显示nivolumab联合化疗具有可耐受的安全性[12],nivolumab联合SOX(S-1,奥沙利铂)组的客观缓解率为57.1%(95%可信区间为30.4~78.2),而联合CAPOX(卡培他滨,奥沙利铂)的客观缓解率为76.5%(50.1~93.2),两组的中位生存期分别为9.7和10.6月。在2021年CSCO指南中推荐在阳性评分CPS≥5时Nivolumab联合化疗(FOLFOX/XELOX)作为晚期GC/GEJ的一线治疗。

2 围手术期免疫联合治疗的进展

多种治疗手段,如新辅助、辅助和围手术期方案,包括不同的化疗和放疗组合,被用以减少胃切除术后的局部和远处复发,并提高患者生存率。然而,目前围手术期最佳的GC全身治疗策略尚未标准化。一项临床试验(NCT04006262)目前正在招募,旨在评估ICIs在失配修复缺陷(dMMR)和(或)微卫星不稳定(MSI)患者的围手术期作用[13]。

2.1 新辅助化疗与免疫治疗

进展期GC经典的NACT方案是表柔比星+顺铂+氟尿嘧啶(ECF)和顺铂+氟尿嘧啶,但5年生存率分别只有36.3%和34%,且两个方案的病理完全缓解率很低[14]。在欧洲具有里程碑意义的Ⅲ期MAGIC试验[15]中,发现与手术组相比,围手术期化疗组(表柔比星、顺铂和输注氟尿嘧啶)显示出更好的OS和更长的PFS,这确立了围手术期ECF化疗方案为可切除的GC和GEJ患者的治疗标准。

最近的一项研究[16]发现,与围手术期ECF/ECX方案相比,围手术期FLOT方案治疗患者的OS增加。此外,FLOT方案治疗下,患者中位OS从35月提高到50月,证明FLOT可能更加有效。MAGIC(英国)[15]、FNCLCC/FFCD ACCORD(法国)[17-18]和FLOT-4(德国)[19]试验确立了NACT是欧洲的标准治疗模式。这也同时说明了即使尚未存在更具说服力的Ⅲ期临床试验,NACT仍被临床上广泛接受,尤其是那些对目前治疗有耐受性的患者。

Li等[20]报道了一例局部晚期胃食管交界癌患者(临床分期为cT4N2M0和Siewert分型Ⅱ型)在围手术期接受ICIs联合NACT后病理完全缓解的病例,该患者病理特点是错配修复完整(mismatch repair proficient, pMMR),PD-L1、EBV均为阴性,但在3周期SOX方案化疗同时加用Camrelizumab(PD-1单抗)200 mg,每隔三周一次,静脉滴注,治疗后提示免疫治疗效果良好。随后患者接受了根治性胃切除术,术后病理检查显示病理分期为ypT0N0M0,病理完全缓解(pathological complete remission, pCR)。患者术后反复CT检查未见肿瘤复发或转移。然而从以往经验来看,该患者术前活检标本提示患者应当对免疫治疗无效、化疗效果有限,但在实际应用中出现了病理完全缓解。考虑可能化疗激发了患者肿瘤内的免疫细胞活性,联合免疫治疗进一步增强了免疫细胞的抗肿瘤作用。

Yu等[21]在一项回顾性研究中发现NACT增加了进展期GC中CD4+、CD8+T细胞的浸润数量和检查点分子的表达,且检查点分子水平的变化相互呈正相关。这可能会提高在进展期GC中应用免疫治疗与化疗甚至双重检查点抑制剂的可能性。

EORTC VESTIGE(NCT03443856)将在接受NACT和手术的高危患者中进行,其目的是通过在辅助治疗环境中联合ICIs(nivolumab和低剂量ipilimumab)与化疗来改善DFS[22]。

此外,IMAGINE试验(NCT04062656)是一项四组化疗控制模块化试验(围手术期化疗-免疫治疗vs.免疫治疗vs.化疗),其目的是评估GC和食管胃交界癌患者的疗效和安全性,结果值得期待,见表 1。

表 1 胃癌新辅助治疗联合免疫治疗临床试验Table 1 Clinical trials of neoadjuvant therapy combined with immunotherapy for gastric cancer

2.2 新辅助放化疗与免疫治疗

术前同步放化疗是可切除和不可切除肿瘤患者的推荐选择,而新辅助放化疗(neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy, NACRT)可提高整体切除率和原发肿瘤的完全手术切除率。更具体地说,NACRT可以更全面地消除微转移的潜在威胁,降低术后复发风险,因此放化疗被认为是局部进展期GC术前治疗的标准方案之一[23]。在食管腺癌和胃食管交界肿瘤新辅助治疗中,放化疗提高了生存期,且患者有良好的耐受性[24]。

在原发放疗部位治疗后,诱导的免疫应答作用,可以清除未经过放疗的转移病灶,甚至出现了肿瘤消退,这种现象称为抗肿瘤治疗的远隔效应(abscopal effect)[25]。但在免疫治疗的大量开展之前,这种现象并不多见。目前已有研究报道,当抗PD-1/L1抗体与化疗和/或放疗联合使用时,可以观察到协同效应[26]。

放射性免疫疗法目前也在研究之中,放疗已被证明可以调节TME,并上调肿瘤和免疫细胞上PD-L1的表达,以达到治疗癌症的效果[26]。在一项病例报告中,放疗联合pembrolizumab能够在复发前的12月内提供疾病控制条件(无需进一步治疗)[27],这意味着放射免疫疗法在联合治疗中可能具有潜力。在围手术期对ICI及其联合治疗的进一步评估可能对局部可切除疾病的患者有益。因此放射治疗和免疫治疗的联合或许能给患者带来意料之外的治疗效果。

Wei等[28]的一项案例报道中,予3例局部进展期胃癌患者(TNM分期:cT3/4aN2M0伴肝胃淋巴结转移(Borrmann分型Ⅳ型)、cT4a/bN3M0(Borrmann分型Ⅲ型)、cT4a/bN3M0(Borrmann分型Ⅲ型))进行了抗PD-1单抗(sintilimab)治疗加放化疗的新辅助治疗。3例患者在中位3.9月后接受了胃切除术,而术后病理分期:ypT3N0M0、ypT0N0M0和ypT3N2M0。3例患者中性粒细胞减少,2~3级。1例患者为2级皮疹,1例患者为1级厌食症和1级非免疫治疗相关性肺炎。治疗期间没有发生因不良事件导致的死亡或停药。

新辅助PD-1阻断加同步放化疗对可能无法切除的局部进展期GC患者具有良好的疗效。目前正在进行一些比较NACT与术前放化疗的随机对照试验,化疗方案主要为ECF、FLOT或DOC(多西他赛、卡培他滨、奥沙利铂)三药方案(NCT02509286(食管)、NCT02931890(GC)、NCT03013010(GC)、NCT04375605(胃食管))。希望通过这些研究可以确定可切除胃腺癌患者的最佳治疗方案。

2.3 靶向治疗与免疫治疗

KEYNOTE-811是一项正在进行的Ⅲ期临床试验(NCT03615326),比较了pembrolizumab与安慰剂在曲妥珠单抗联合化疗时的效果[29]。一项研究对先前接受治疗的晚期GC患者的ramucirumab联合pembrolizumab,以安全性和耐受性为主要终点,发现这种方案可以提供良好的耐受性和潜在疗效(疾病控制率68%;中位PFS 5.3月)[30]。

一项Ⅱ期研究(EPOC1706)评估了lenvatinib加pembrolizumab在一线或二线晚期GC患者中的抗肿瘤活性和安全性:29例患者中有20例发现客观缓解,表明其疗效优于以往的单一药物,安全性也可以被接受[31]。这一令人瞩目的研究成果强调小分子靶向治疗联合免疫治疗能够在临床应用中带来更好的安全性和抗肿瘤活性,也提示联合方案探索的必要性。

另一项Ⅱ期试验(NCT03878472)将针对局部晚期近端GC患者进行,旨在评估抗PD-1单抗与apatinib(一种新型抗血管生成的血管内皮生长因子2(VEGFR2)酪氨酸激酶抑制剂)联合使用或不使用化疗(S1/奥沙利铂)在新辅助治疗中的益处,相关的研究成果也值得进一步关注和探索。

2.4 其他新辅助联合免疫治疗

其他针对晚期GC/GEJC的试验正在评估各种基于抗PD-1/PD-L1的策略,包括在一线和后线环境下给药,以及作为组合(与化疗或针对其他免疫检查点蛋白的药物,如CTLA-4、LAG-3和IDO)或转换维持的方案。

双重免疫疗法也显示出良好的效果。例如,在CheckMate-032试验[32]中,nivolumab加ipilimumab对化疗难治性食管胃癌患者表现出抗肿瘤效果,更多评估这种组合在食管胃癌早期治疗中的Ⅲ期研究正在进行中。免疫疗法联合化疗和靶向治疗也显示出良好的临床治疗效果。

其他的ICIs,如avelumab(一种抗PD-L1单克隆抗体)、atezolizumab(一种抗CTLA-4单克隆抗体)也将被开发(NCT03399071, NCT03448835, NCT03421288)。在这些试验中,有一项(NCT03421288)正在评估atezolizumab联合FLOT在胃腺癌患者围手术期治疗中的作用[33]。

一项ⅠB期研究评估在可手术的Ⅱ/Ⅲ期食管癌/胃食管交界处癌症的手术切除前,抗PD-1(nivolumab)或抗PD1/抗LAG-3(relatlimab)在术前与化疗放疗相结合,可以促进TME的细胞和分子特征的变化,提高生存率,见表 1。

目前一项临床试验正在开展新辅助经导管动脉化疗栓塞术(transcatheter arterial embolization, TACE)和PD-1抗体Tislelizumab的联合治疗(NCT04799548)。

3 结语与展望

新辅助治疗研究现状提示,免疫联合化疗在临床实践中有较好的治疗效果,但除此之外应用免疫治疗单药或者联合用药的新辅助治疗的定义、诊断、疗效还没有统一标准,因此不能客观评价疗效。目前,研究针对免疫治疗后手术患者术后分析不足,这也导致了不同国家和地区对这类新辅助治疗中应用免疫治疗的疗效存在着不同甚至相反的观点。在微卫星不稳定的患者中ICIs联合化疗或者ICIs联合抗血管生成或者三者联用都能在治疗晚期GC中显示较好的缓解率和生存受益,可能也将成为未来肿瘤治疗的趋势之一。目前能用作预测三者联用的生物标志物尚不明确,并且临床应用中化疗是新辅助治疗的首选,三者之间的不良反应相对单药有所增加,也需要大样本试验证明。

未来在免疫治疗不断更新迭代的情况下,关于新辅助治疗联合免疫治疗的临床应用也会逐年增多,因此如何最大程度增加患者的健康保障成为亟需解决的问题。我们认为未来新辅助治疗中应用ICIs的策略应该是:(1)积极探索预测ICIs疗效的特异性生物标志物,包括免疫检查点、共刺激分子、免疫标志物等,增强个性化用药选择;(2)提高相关临床试验样本量,探索ICIs与化疗药、放疗、分子靶向等联合治疗中晚期GC的合理治疗顺序和剂量、药物的配伍和方案,以更加详实的数据供后续临床应用或指南制定参考,最大程度提高患者预后,降低不良事件。

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。作者贡献:刘彦:实验实施、文稿撰写秦凡博:实验实施龚建平:数据整理及文章终审张文锋:数据整理、文章终审及基金支持 -

表 1 不同时间点热消融不全HepG2细胞模型中CD133的表达

Table 1 Expression of CD133 in residual HepG2 cell models of insufficient thermal ablation at different time points

表 2 不同浓度的苦龙胆酯苷处理热消融不全HepG2细胞24 h后CD133的表达

Table 2 CD133 expressionin the models of insufficient thermal ablation HepG2 cells after treatment with different concentrations of amarogentin

表 3 苦龙胆酯苷对热消融不全HepG2细胞增殖、凋亡及相关分子的影响

Table 3 Effects of amarogentin on proliferation, apoptosis, and related molecules of insufficient thermal ablation HepG2 cells

-

[1] Donne R, Lujambio A. The Liver Cancer Immune Microenvironment: Therapeutic Implications for Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Hepatology, 2022, 77(5): 1773-1796.

[2] Huang AC, Dodge JL, Yao FY, et al. National Experience on Waitlist Outcomes for Down-staging of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: High Dropout Rate in "All-Comers"[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2023, 21(6): 1581-1589. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.08.023

[3] Deng Q, He M, Fu C, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Int J Hyperthermia, 2022, 39(1): 1052-1063. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2022.2059581

[4] Zhu S, Wu Y, Zhang X, et al. Targeting N7-Methylguanosine tRNA modification blocks hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis after insufficient radiofrequency ablation[J]. Mol Ther, 2023, 31(6): 1596-1614. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.08.004

[5] Zou YW, Ren ZG, Sun Y, et al. The latest research progress on minimally invasive treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int, 2023, 22(1): 54-63. doi: 10.1016/j.hbpd.2022.08.004

[6] Chen L, Zhang W, Sun T, et al. Effect of Transarterial Chemoembolization Plus Percutaneous Ethanol Injection or Radiofrequency Ablation for Liver Tumors[J]. J Hepatocell Carcinoma, 2022, 9: 783-797. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S370486

[7] Dong S, Li Z, Kong J, et al. Arsenic trioxide inhibits angiogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma after insufficient radiofrequency ablation via blocking paracrine angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2[J]. Int J Hyperthermia, 2022, 39(1): 888-896. doi: 10.1080/02656736.2022.2093995

[8] Guo Y, Ren Y, Dong X, et al. An Overview of Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Insufficient Radiofrequency Ablation[J]. J Hepatocell Carcinoma, 2022, 9: 343-355. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S358539

[9] Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Amarogentin Inhibits Liver Cancer Cell Angiogenesis after Insufficient Radiofrequency Ablation via Affecting Stemness and the p53-Dependent VEGFA/Dll4/Notch1 Pathway[J]. Biomed Res Int, 2020, 2020: 5391058.

[10] Wang S, Liu J, Wu H, et al. All-trans retinoic acid (ATRA) inhibits insufficient radiofrequency ablation (IRFA)-induced enrichment of tumor-initiating cells in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Chin J Cancer Res, 2021, 33(6): 694-707. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2021.06.06

[11] Zhang X, Zheng Q, Yue X, et al. ZNF498 promotes hepatocellular carcinogenesis by suppressing p53-mediated apoptosis and ferroptosis via the attenuation of p53 Ser46 phosphorylation[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2022, 41(1): 79. doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02288-3

[12] Xiao Y, Chen J, Zhou H, et al. Combining p53 mRNA nanotherapy with immune checkpoint blockade reprograms the immune microenvironment for effective cancer therapy[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 758. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28279-8

[13] Delman M, Avcı ST, Akçok İ, et al. Antiproliferative activity of (R)-4'-methylklavuzon on hepatocellular carcinoma cells and EpCAM+/CD133+ cancer stem cells via SIRT1 and Exportin-1 (CRM1) inhibition[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2019, 180: 224-237. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.024

[14] Pustovalova M, Blokhina T, Alhaddad L, et al. CD44+ and CD133+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Cells Exhibit DNA Damage Response Pathways and Dormant Polyploid Giant Cancer Cell Enrichment Relating to Their p53 Status[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 23(9): 4922. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094922

[15] Choi HY, Siddique HR, Zheng M, et al. p53 destabilizing protein skews asymmetric division and enhances NOTCH activation to direct self-renewal of TICs[J]. Nat Commun, 2020, 11(1): 3084. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16616-8

[16] Machida K. Cell fate, metabolic reprogramming and lncRNA of tumor-initiating stem-like cells induced by alcohol[J]. Chem Biol Interact, 2020, 323: 109055. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2020.109055

[17] Song B, Zhou W. Amarogentin has protective effects against sepsis-induced brain injury via modulating the AMPK/SIRT1/NF-κB pathway[J]. Brain Res Bull, 2022, 189: 44-56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.08.018

[18] Pal D, Sur S, Roy R, et al. Hypomethylation of LIMD1 and P16 by downregulation of DNMT1 results in restriction of liver carcinogenesis by amarogentin treatment[J]. J Biosci, 2021, 46: 53. doi: 10.1007/s12038-021-00176-0

[19] Sur S, Pal D, Banerjee K, et al. Amarogentin regulates self renewal pathways to restrict liver carcinogenesis in experimental mouse model[J]. Mol Carcinog, 2016, 55(7): 1138-1149. doi: 10.1002/mc.22356

[20] Ma H, Li Z, Yuan J, et al. Extrapolating Prognostic Factors of Primary Curative Resection to Postresection Recurrences Hepatocellular Carcinoma Treatable by Radiofrequency Ablation[J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2021, 2021: 8878417.

[21] Chen X, Huang Y, Chen H, et al. Augmented EPR effect post IRFA to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of arsenic loaded ZIF-8 nanoparticles on residual HCC progression[J]. J Nanobiotechnology, 2022, 20(1): 34. doi: 10.1186/s12951-021-01161-3

[22] Wang F, Xu C, Li G, et al. Incomplete radiofrequency ablation induced chemoresistance by up-regulating heat shock protein 70 in hepatocellular carcinoma[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2021, 409(2): 112910. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2021.112910

[23] Tong Y, Yang H, Xu X, et al. Effect of a hypoxic microenvironment after radiofrequency ablation on residual hepatocellular cell migration and invasion[J]. Cancer Sci, 2017, 108(4): 753-762. doi: 10.1111/cas.13191

[24] Zaimoku R, Miyashita T, Tajima H, et al. Monitoring of Heat Shock Response and Phenotypic Changes in Hepatocellular Carcinoma After Heat Treatment[J]. Anticancer Res, 2019, 39(10): 5393-5401. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.13733

[25] Pal D, Sur S, Mandal S, et al. Prevention of liver carcinogenesis by amarogentin through modulation of G1/S cell cycle check point and induction of apoptosis[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2012, 33(12): 2424-2431. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs276

[26] Pal D, Sur S, Roy R, et al. Epigallocatechin gallate in combination with eugenol or amarogentin shows synergistic chemotherapeutic potential in cervical cancer cell line[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2018, 234(1): 825-836.

[27] Park EK, Lee JC, Park JW, et al. Transcriptional repression of cancer stem cell marker CD133 by tumor suppressor p53[J]. Cell Death Dis, 2015, 6(11): e1964. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.313

[28] Xu Y, Xu Z, Li Q, et al. Mutated p53 Promotes the Symmetric Self-Renewal of Cisplatin-Resistant Lung Cancer Stem-Like Cells and Inhibits the Recruitment of Macrophages[J]. J Immunol Res, 2019, 2019: 7478538.

[29] Feldman DE, Chen C, Punj V, et al. The TBC1D15 oncoprotein controls stem cell self-renewal through destabilization of the Numb-p53 complex[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e57312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057312

[30] Machida K, Feldman DE, Tsukamoto H. TLR4-dependent tumor-initiating stem cell-like cells (TICs) in alcohol-associated hepatocellular carcinogenesis[J]. Adv Exp Med Biol, 2015, 815: 131-144.

[31] Espinosa-Sánchez A, Suárez-Martínez E, Sánchez-Díaz L, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Signaling Pathways Related to Cancer Stemness[J]. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 1533.

下载:

下载: