-

摘要:

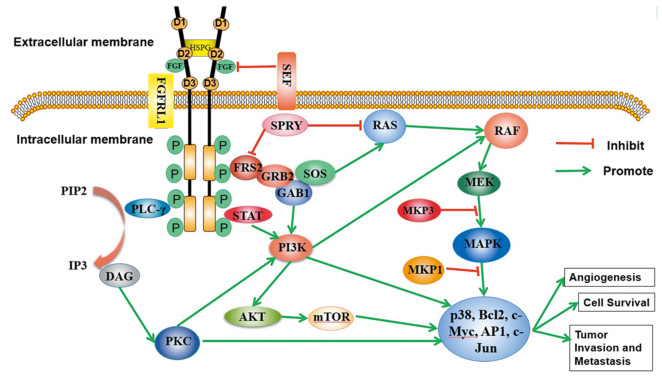

成纤维细胞生长因子受体(FGFR)信号的异常在多种肿瘤中被发现,FGFR信号的异常参与了肿瘤发生的多项进程,包括细胞存活、增殖、炎性反应、迁移、血管生成、上皮间质转化及耐药。故FGFR是治疗肿瘤有应用前景的靶点,越来越多的FGFR抑制剂进入临床前研究及临床研究阶段,部分FGFR抑制剂已被批准应用于临床。但是获得性耐药及全身毒性等问题阻碍了FGFR抑制剂的应用。本文综述了常见FGFR抑制剂的临床应用并对其中出现的问题及解决措施作一总结。

Abstract:Abnormal FGFR signaling has been found in a variety of cancers. The abnormal FGFR signaling is involved in several processes of tumorigenesis which include cell survival, proliferation, inflammation, migration, angiogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and drug resistance. Therefore, FGFR is a very promising target for the treatment of tumors. More and more FGFR inhibitors have been developed for preclinical and clinical trials, and some FGFR inhibitors have been used in clinical applications. However, the problems such as acquired resistance and systemic toxicity have hindered the application of FGFR inhibitors. This paper reviews the clinical application of common FGFR inhibitors and summarizes the problems and solutions in their application.

-

Key words:

- Cancer /

- FGFR /

- FGF /

- Targeted therapy /

- FGFR inhibitors /

- Signal pathway

-

0 引言

目前,全球癌症的发病和死亡人数仍在持续增长,2020年新发肿瘤1 929.3万例、死亡995.8万例,癌症在许多国家的死因顺位上已经超越心血管疾病等高死亡率慢性疾病[1]。沈阳市城区居民全死因中,恶性肿瘤也仅次于心脏病[2],严重危害沈阳人民健康。为了解沈阳市城区居民恶性肿瘤发病及生存情况,并提出防治措施,现对2011—2018年沈阳市城区居民恶性肿瘤发病及生存趋势进行分析。

1 资料与方法

1.1 资料来源

2011—2018年沈阳市城区恶性肿瘤发病和生存资料来源于中国肿瘤登记中心肿瘤随访与登记报告系统。报告范围为具有沈阳市城市国家级监测点(和平区、沈河区、大东区、皇姑区和铁西区)户籍居民发病的全部恶性肿瘤(ICD10编码C00-C97)。人口资料来源于沈阳市公安局提供的每年份性别、年龄别的平均人口数。

1.2 质量评价

根据《中国肿瘤登记工作指导手册》[3]和国际癌症研究中心(IARC)/国际癌症登记协会(IACR)[4-5]对登记质量的有关要求,对数据的可靠性、完整性、有效性进行评估。沈阳市城区肿瘤发病数据从2008年起连续五年被国际五大洲癌症协会收录,连续十年被中国肿瘤登记年报收录。沈阳市城区2011—2018年上报新发肿瘤数据质量评价为病理诊断率(MV%)为66.63%、只有死亡医学证明书比例(DCO%)为2.43%、死亡发病比(M/I)为0.65,均符合质量要求。

1.3 统计学方法

提取2011—2018年沈阳城区恶性肿瘤发病数据,以国际疾病分类法ICD-10进行分类,并用IARCcrgTools软件进行数据审核。利用Excel2007计算粗发病率、标化率(中标率、世标率)、年龄别发病率、累积发病率(0~74岁)、截缩发病率(35~64岁)、前十位肿瘤发病顺位和生存率等指标;利用SPSS23.0统计软件对恶性肿瘤男女发病率及生存率进行χ2检验,检验水准α=0.05;采用寿命表法计算观察生存率,病例随访时间截止至2020-12-31;采用EdererⅡ方法(Ederer and Heise, 1959)计算期望生存率(expected survival rate, ESR)和相对生存率(relative survival rate, RSR);利用美国癌症中心研究所开发的Joinpoint 3.5.3软件计算发病率和生存率年度变化百分比(APC%),检验水准α=0.05。中标率采用2000年全国人口普查,世标率采用Segi's世界标准人口结构进行计算。

2 结果

2.1 总体发病分布

2011—2018年沈阳市上报新发恶性肿瘤109 873例,发病率为364.70/10万,中标率190.00/10万,世标率185.63/10万,0~74岁累积率为21.17%,35~64岁截缩率为311.66/10万。2011—2014年男、女、合计恶性肿瘤发病率及标化率均呈大幅上升趋势(P < 0.01);2015—2018年男、女、合计恶性肿瘤发病率缓慢上升但标化率缓慢下降(P≥0.05),见表 1。

表 1 2011—2018年沈阳市城区居民恶性肿瘤发病率(1/105)Table 1 Malignant tumor incidence of urban residents in Shenyang from 2011 to 2018 (1/105)

2.2 性别分布

2011—2018年沈阳市城区恶性肿瘤男性发病率为380.62/10万,女性发病率为349.42/10万,男、女发病率之比为1.09:1,8年间男性恶性肿瘤发病率高于女性,差异有统计学意义(χ2=201.63, P < 0.05),见表 1。

2.3 年龄分布

多数肿瘤在0~30岁组开始发病,30~40岁组缓慢上升,在40岁以后开始大幅度上升,在80~岁组达到发病高峰,85+岁组发病率略有下降,这可能与85+岁组人口急剧减少有关。男女以50~55岁组为界,发病率呈现X形状,见图 1。

2.4 发病顺位

2011—2018年沈阳市城区男性恶性肿瘤发病前10位的依次是肺癌、结直肠癌、肝癌、胃癌、膀胱癌、食管癌、胰腺癌、前列腺癌、肾癌、甲状腺癌;其中前5位肺癌(28.77%)、结直肠癌(16.40%)、肝癌(9.18%)、胃癌(9.15%)、膀胱癌(4.36%)占男性恶性肿瘤的67.86%。8年间肺癌、结直肠癌、膀胱癌、胰腺癌、前列腺癌、肾癌、甲状腺癌发病率均呈上升趋势(P < 0.05);而肝癌(P=0.00, P=0.05)、胃癌(P=0.02, P=0.07)、食管癌(P=0.08, P=0.24)发病率则先上升后下降,见表 2。

表 2 2011—2018年沈阳市城区男性恶性肿瘤发病顺位(1/105)Table 2 Incidence rank of malignant tumors in male residents in urban areas of Shenyang from 2011 to 2018 (1/105)

女性恶性肿瘤发病率前10位的依次是乳腺癌、肺癌、结直肠癌、宫颈癌、甲状腺癌、胃癌、肝癌、卵巢癌、胰腺癌、子宫体癌;其中前5位乳腺癌(22.63%)、肺癌(18.72%)、结直肠癌(12.84%)、宫颈癌(5.73%)、甲状腺癌(5.71%)占女性恶性肿瘤65.63%;8年间除宫颈癌、胃癌、肝癌、卵巢癌、子宫体癌外,乳腺癌、肺癌、结直肠癌、甲状腺癌、胰腺癌发病率均呈上升趋势(P < 0.05),见表 3。

表 3 2011—2018年沈阳市城区女性恶性肿瘤发病顺位(1/105)Table 3 Incidence rank of malignant tumors in female residents in urban areas of Shenyang from 2011 to 2018 (1/105)

2.5 恶性肿瘤5年生存率

2011—2015年沈阳市城区居民恶性肿瘤5年生存率为40.49%,相对生存率为47.84%。5年间合计观察生存率呈上升趋势,差异有统计学意义(P=0.04),其中男性为31.82%,女性为49.58%,男女观察生存率均呈上升趋势(P=0.04, P=0.03),且女性5年生存率高于男性(χ2=187.62, P < 0.05),见表 4。

表 4 2011—2015年沈阳市城区居民恶性肿瘤5年生存率(%)Table 4 Five-year survival rate of malignant tumors in urban residents in Shenyang from 2011 to 2015 (%)

2.6 发病前十位恶性肿瘤5年生存率顺位

2011—2015年沈阳市城区男性发病前十位的恶性肿瘤5年生存率顺位依次是甲状腺癌(86.25%)、肾癌(64.19%)、膀胱癌(59.43%)、结直肠癌(48.41%)、前列腺癌(47.55%)、胃癌(31.63%)、食管癌(20.56%)、肝癌(17.20%)、肺癌(16.79%)、胰腺癌(8.67%),见表 5。女性依次是甲状腺癌(91.81%)、乳腺癌(76.50%)、子宫体癌(73.17%)、子宫颈癌(65.18%)、结直肠癌(49.04%)、卵巢癌(43.34%)、胃癌(32.47%)、肺癌(21.20%)、肝癌(14.41%)、胰腺癌(10.01%),见表 6。

表 5 2011—2015年沈阳市城区男性发病前十位恶性肿瘤5年生存率(%)Table 5 Five-year survival rate of top ten malignant tumors among males in urban areas of Shenyang from 2011 to 2015 (%) 表 6 2011—2015年沈阳市城区女性发病前十位恶性肿瘤5年生存率(%)Table 6 Five-year survival rate of top ten malignant tumors among females in urban areas of Shenyang from 2011 to 2015 (%)

表 6 2011—2015年沈阳市城区女性发病前十位恶性肿瘤5年生存率(%)Table 6 Five-year survival rate of top ten malignant tumors among females in urban areas of Shenyang from 2011 to 2015 (%)

男女5年生存率最高均为甲状腺癌,最低均为胰腺癌。相同癌种中,肺癌、甲状腺癌5年生存率女性高于男性(χ2=48.29, χ2=9.85, P < 0.01),差异有统计学意义;肝癌男性高于女性(χ2=5.32, P < 0.05),差异有统计学意义;结直肠癌(χ2=0.37, P≥0.05)、胃癌(χ2=0.33, P≥0.05)、胰腺癌(χ2=0.99, P≥0.05)男女5年生存率差异无统计学意义。

2.7 发病前十位恶性肿瘤5年生存率变化趋势

2011—2015年沈阳市男性发病前十位的恶性肿瘤除结直肠癌、前列腺癌、肝癌外,其余七位中,甲状腺癌(APC%=12.97, P=0.03)、肾癌(APC%=7.86, P=0.01)、膀胱癌(APC%=10.04, P=0.00)、胃癌(APC%=6.57, P=0.05)、食管癌(APC%=6.05, P=0.03)、肺癌(APC%=11.81, P=0.04)、胰腺癌(APC%=25.57, P=0.02)5年生存率均呈上升趋势,见表 5。

女性发病前十位的恶性肿瘤除子宫体癌、结直肠癌、胃癌、肺癌外,其余六位的甲状腺癌(APC%=7.93, P=0.01)、乳腺癌(APC%=3.87, P=0.05)、宫颈癌(APC%=4.96, P=0.00)、卵巢癌(APC%=10.75, P=0.03)、肝癌(APC%=20.09, P=0.01)、胰腺癌(APC%=49.75, P=0.01)5年生存率均呈上升趋势,见表 6。

3 讨论

从发病情况看,沈阳市2011—2018年城区居民恶性肿瘤发病率持续上升(P=0.00, P=0.67),发病中标率(190.00/10万)低于2015年中国城市恶性肿瘤发病中标率(193.93/10万)[6]和中国东部恶性肿瘤发病中标率(194.36/10万)[7],高于中部恶性肿瘤发病中标率(183.36/10万)[8],低于2006—2015年辽宁省五城市恶性肿瘤标化发病率(199.15/10万)[9],高于2016年安徽(179.70/10万)[10]和江苏(182.61/10万)[11]、2017年黑龙江(174.27/10万)[12],目前发病率处于全国中等水平。

2011—2018年沈阳市恶性肿瘤发病率男性高于女性(χ2=201.63, P < 0.05),与中国分布相一致[13],且随着年龄的增长呈明显上升趋势,而沈阳市老龄人口亦呈逐年上升趋势,这既反映了人口老龄化进程的加快,也反映了癌症相关危险因素暴露时间的增加[14]是沈阳市癌症高发的重要原因。因此要针对病因和危险因素,致力于通过精准、适度和有效的干预,降低癌症发生风险。

2011—2018年男女恶性肿瘤发病顺位前三位与国家《2018肿瘤登记年报》发布中国城市数据[8]一致。8年间,男性发病前十位除肝癌、胃癌、食管癌发病率先上升后下降,其他癌种均呈上升趋势;女性除了妇科肿瘤和肝癌、胃癌外,其他发病前十的恶性肿瘤发病率均呈上升趋势。研究表明与感染或贫困相关的癌症正逐渐被经济发达国家的常见癌症所取代[15]。而沈阳市由于经济的发展和生活水平的提高,不良生活方式的加剧,不仅原有主要高发癌症尚未有明显下降趋势,西方国家高发的大肠癌、前列腺癌和女性乳腺癌等癌症发病又迅速增加。

从生存情况看,2011—2015年沈阳市城区恶性肿瘤5年观察生存率为40.49%、相对生存率为47.84%,接近于2018年全国公布的全部癌症的5年生存率(40.5%)[16],2019年辽宁省公布的城市癌症5年标化生存率(41.5%)[17],2012—2016年上海市青浦区5年相对生存率为47.41%[18],高于姑苏区2008—2013年癌症患者的5年相对生存率(42.2%)[19]。女性的生存率总体高于男性(χ2=187.62, P < 0.05)。

随着医疗技术水平的提升,沈阳市癌症5年生存率也大幅上升,但仍有部分癌种5年生存率无上升趋势,这与癌症种类构成不同和筛查手段落后造成生存率差异有重要关系。2011—2015年沈阳市城区恶性肿瘤5年生存率最高的癌种为甲状腺癌,其次是女性的乳腺癌(76.50%)、子宫体癌(73.17%)、宫颈癌(65.18%);男女生存率排在后三位是肝癌(17.20%、14.41%)、肺癌(16.79%、21.20%)、胰腺癌(8.67%、10.01%);生存率最低的均为胰腺癌。而这些生存率较高的癌症可以通过早期筛查项目,寻找出高危人群或早期患者,进行早发现、早诊断和早治疗的“二级预防”,是有效提升癌症生存的关键手段;对于生存率较低的癌症我们要依托于生物医学各学科不断发展的各种新技术、新手段,不断探索癌症相关标志物,优化筛查策略,早期发现、规范治疗,以提升患者生存率。

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.作者贡献:张静:文章的文献检索,论文撰写王琛、谷保红、张雅晴、陈昊:文章的修改 -

[1] Chioni AM, Grose RP. Biological Significance and Targeting of the FGFR Axis in Cancer[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2021, 13(22): 5681. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225681

[2] Roskoski RJ. The role of fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) protein-tyrosine kinase inhibitors in the treatment of cancers including those of the urinary bladder[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2020, 151: 104567. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104567

[3] Regeenes R, Silva PN, Chang HH, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 5 (FGFR5) is a co-receptor for FGFR1 that is up-regulated in beta-cells by cytokine-induced inflammation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2018, 293(44): 17218-17228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.003036

[4] Xie Y, Su N, Yang J, et al. FGF/FGFR signaling in health and disease[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020, 5(1): 181. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00222-7

[5] Helsten T, Elkin S, Arthur E, et al. The FGFR landscape in cancer: Analysis of 4, 853 tumors by next-generation sequencing[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2016, 22(1): 259-267. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-3212

[6] 张岩, 葛友进, 袁都求, 等. FGFR抑制剂的研究进展[J]. 肿瘤药学, 2020, 10(5): 513-518, 530. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1264.2020.05.01 Zhang Y, Ge YJ, Yuan DQ, et al. Research Progress of FGFR Inhibitors[J]. Zhong Liu Yao Xue, 2020, 10(5): 513-518, 530. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-1264.2020.05.01

[7] Han B, Li K, Wang Q, et al. Effect of anlotinib as a third-line or further treatment on overall survival of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: The ALTER 0303 phase 3 randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Oncol, 2018, 4(11): 1569-1575. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.3039

[8] Chi Y, Yao Y, Fang Z, et al. 1693P-Efficacy and safety of anlotinib in advanced leiomyosarcoma: Subgroup analysis of a phase IIB trial (ALTER0203)[J]. Ann Oncol, 2019, 30(Suppl 5): v694.

[9] Liu Y, Cheng Y, Wang Q, et al. 1787P Effect of anlotinib in advanced small cell lung cancer patients with pleural metastases/pleural effusion: A subgroup analysis from a randomized, double-blind phase Ⅱ trial (ALTER1202)[J]. Ann Oncol, 2020, 31(Suppl 4): S1036.

[10] Markham A. Erdafitinib: First Global Approval[J]. Drugs, 2019, 79(9): 1017-1021. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01142-9

[11] Loriot Y, Necchi A, Park SH, et al. Erdafitinib in Locally Advanced or Metastatic Urothelial Carcinoma[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 381(4): 338-348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1817323

[12] Montazeri K, Bellmunt J. Erdafitinib for the treatment of metastatic bladder cancer[J]. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol, 2020, 13(1): 1-6. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2020.1702025

[13] Hoy SM. Pemigatinib: First Approval[J]. Drugs, 2020, 80(9): 923-929. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01330-y

[14] Abou-Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A, et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study[J]. Lancet Oncol, 2020, 21(5): 671-684. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30109-1

[15] Kang C. Infigratinib: First Approval[J]. Drugs, 2021, 81(11): 1355-1360. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01567-1

[16] Javle M, Roychowdhury S, Kelley RK, et al. Infigratinib (BGJ398) in previously treated patients with advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma with FGFR2 fusions or rearrangements: mature results from a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study[J]. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 6(10): 803-815. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00196-5

[17] Katoh M. FGFR inhibitors: Effects on cancer cells, tumor microenvironment and whole-body homeostasis (Review)[J]. Int J Mol Med, 2016, 38(1): 3-15. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2016.2620

[18] Wu D, Guo M, Min X, et al. LY2874455 potently inhibits FGFR gatekeeper mutants and overcomes mutation-based resistance[J]. Chem Commun (Camb), 2018, 54(85): 12089-12092. doi: 10.1039/C8CC07546H

[19] Carter EP, Fearon AE, Grose RP. Careless talk costs lives: fibroblast growth factor receptor signalling and the consequences of pathway malfunction[J]. Trends Cell Biol, 2015, 25(4): 221-233. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.11.003

[20] Rizzo A, Ricci AD, Brandi G. Futibatinib, an investigational agent for the treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: evidence to date and future perspectives[J]. Expert Opin Investig Drugs, 2021, 30(4): 317-324. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2021.1837774

[21] Raja A, Park I, Haq F, et al. FGF19-FGFR4 Signaling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma[J]. Cells, 2019, 8(6): 536. doi: 10.3390/cells8060536

[22] Quintanal-Villalonga A, Ferrer I, Molina-Pinelo S, et al. A patent review of FGFR4 selective inhibition in cancer (2007-2018)[J]. Expert Opin Ther Pat, 2019, 29(6): 429-438. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1624720

[23] Fairhurst RA, Knoepfel T, Buschmann N, et al. Discovery of Roblitinib(FGF401) as a Reversible-Covalent Inhibitor of the Kinase Activity of Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 4[J]. J Med Chem, 2020, 63(21): 12542-12573. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01019

[24] No authors listed. FGFR Inhibitor Stymies Gastric Cancer[J]. Cancer Discov, 2021, 11(5): OF3. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-NB2021-0312

[25] Herbert C, Schieborr U, Saxena K, et al. Molecular Mechanism of SSR128129E, an Extracellularly Acting, Small-Molecule, Allosteric Inhibitor of FGF Receptor Signaling[J]. Cancer Cell, 2016, 30(1): 176-178. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.015

[26] Ilya T, John L, Evgenia S, et al. Corrigendum to 'Targeting FGFR2 with alofanib (RPT835) shows potent activity in tumour models' [Eur J Cancer 61 (2016) 20-28][J]. Eur J Cancer, 2017, 70: 156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.11.001

[27] Zhou Y, Wu C, Lu G, et al. FGF/FGFR signaling pathway involved resistance in various cancer types[J]. J Cancer, 2020, 11(8): 2000-2007. doi: 10.7150/jca.40531

[28] Yue S, Li Y, Chen X, et al. FGFR-TKI resistance in cancer: current status and perspectives[J]. J Hematol Oncol, 2021, 14(1): 23. doi: 10.1186/s13045-021-01040-2

[29] Tan L, Wang J, Tanizaki J, et al. Development of covalent inhibitors that can overcome resistance to frst-generation FGFR kinase inhibitors[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014, 111(45): E4869-E4877.

[30] Yoza K, Himeno R, Amano S, et al. Biophysical characterization of drug-resistant mutants of fibroblast growth factor receptor 1[J]. Genes Cells, 2016, 21(10): 1049-1058. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12405

[31] Liang Q, Wang J, Zhao L, et al. Recent advances of dual FGFR inhibitors as a novel therapy for cancer[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2021, 214: 113205. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113205

[32] Chen CH, Changou CA, Hsieh TH, et al. Dual inhibition of PIK3C3 and FGFR as a new therapeutic approach to treat bladder cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(5): 1176-1189. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2066

-

期刊类型引用(3)

1. 贺明,汤成,梁艳,黄义娟,陶然. 2014-2016年重庆市九龙坡区新发恶性肿瘤生存分析. 社区医学杂志. 2023(03): 115-118+123 .  百度学术

百度学术

2. 李红,徐幽琼,郑婉辉,陆璐. 福州市2018年恶性肿瘤发病与死亡分析. 现代肿瘤医学. 2023(18): 3481-3485 .  百度学术

百度学术

3. 亓琳,张欢欢,沈自芳,杨蕊. 彩色多普勒超声特征对乳腺无症状炎性改变和浸润性导管癌的鉴别诊断价值. 中国医药导报. 2023(28): 164-167 .  百度学术

百度学术

其他类型引用(0)

下载:

下载: