Cancer Stem Cells Niche in Colorectal Cancer: Take Paneth Cells as an Example

-

摘要:

近年来,对肿瘤干细胞巢的深入研究开启了肿瘤研究的“巢”时代,结直肠癌是实体肿瘤的典型代表,有较为典型的发生发展机制,是肿瘤干细胞巢研究的可靠模型。潘氏细胞是正常肠上皮的重要组成细胞,对肠干细胞具有重要的支持、保护等作用,是肠干细胞巢的关键成分之一。然而目前在结肠上皮恶性转化中,以潘氏细胞为代表的干细胞巢成分的作用如何尚有待研究,进一步研究潘氏细胞和肠干细胞的相互关系,从而推导其在结肠肿瘤不同发展阶段的可能作用,将有助于对肿瘤干细胞巢的进一步了解,同时也可为结直肠癌临床治疗提供潜在的新靶点。

Abstract:In recent years, accumulating studies in cancer stem cells niche gradually opened an era of “niche time”. As one of the classical solid tumors, colorectal cancer presented a relatively clear process of cancer initiating and development, which would be an ideal model for niche research. Paneth cells, which play a key role in supporting and protecting the intestine stem cells, are important element of normal intestinal epithelium and also one of the major components of the stem cells niche. However, the potential role of these cells, take the Paneth cells for example, on the road of colorectal epithelium malignant transformation are still largely unknown. Further studies aimed to uncover the relationship of Paneth cells with the intestine stem cells and its role in different stages of colorectal tumor development could expand the knowledge of cancer stem cells niche, also, could help to find the potential new therapeutic targets for colorectal cancer treatment in future.

-

Key words:

- Cancer stem cells /

- Niche /

- Colorectal cancer /

- Paneth cells /

- Signaling pathway

-

0 引言

结肠癌是常见的胃肠道恶性肿瘤之一,我国2015年新发结直肠肿瘤达37.63万例,死亡19.1万例,不论是新发病例还是死亡病例,均位列恶性肿瘤前5位[1]。肿瘤干细胞及肿瘤干细胞巢已成为近年来的研究热点,即将开启肿瘤研究的“巢时代”。然而到目前为止,许多研究难点仍未获得突破性进展。结直肠癌是实体肿瘤的典型代表,具有相对清晰的发生发展过程,现以正常肠上皮细胞组成成分之一的潘氏细胞为例,浅析此类细胞在结直肠肿瘤恶性转变中的可能作用,为未来肿瘤干细胞巢研究提供一定借鉴。

1 正常肠上皮细胞组成成分及潘氏细胞的主要作用

人类的肠道系统大体上可分为小肠和结肠,其上皮细胞来源在胚胎发育上均起源于内胚层,全部小肠和右半结肠来源于中肠,而左半结肠来源于后肠。这种同源性决定了小肠和结肠在组织结构上的相似,但由于两者功能上的差异,使得在肠上皮组成成分上有所不同,而有意思的是同样是结肠,在某些时候,右半结肠和左半结肠仍展示了这种起源上的细微差异。

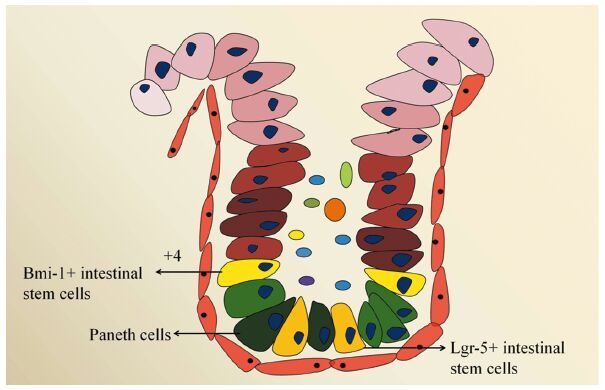

健康者肠上皮由以下几类细胞组成,分别是肠干细胞、潘氏细胞、肠上皮细胞、肠内分泌细胞、杯状细胞以及Tuft细胞等,见图 1,这些细胞从下往上依次排列,形成肠腺窝。人类肠上皮经历着快速的更替过程,平均更替时间为3~4天,但有两种细胞的更替周期有所不同,这就是分布在腺窝底部的肠干细胞和潘氏细胞。对于肠干细胞,目前认为其存在两类不同来源,分别为Lgr-5阳性的干细胞和Bmi-1阳性的干细胞(+4位置),其中前者分布在潘氏细胞环绕之中,处于高度活跃状态,是肠上皮不断更替的主要动力;后者位置一般分布在潘氏细胞之上,相对不活跃,目前研究较少[2]。

除肠干细胞外,潘氏细胞是存活时间较长的肠上皮细胞(更替时间约为1月),于1872年被Schwalbe发现。但直到1888年,澳大利亚生物学家Josef Paneth对其进行准确描述后才被正式命名[3]。经过近一个世纪的研究,目前发现潘氏细胞主要在维持肠上皮完整性、肠道先天性免疫、肠道抗菌抗炎等方面起作用,这些作用的物质基础在于潘氏细胞能够分泌多种物质,如肠抗菌肽、防御素、溶菌霉素、磷脂酶和C型凝集素等[4]。除此之外,潘氏细胞对肠干细胞的支持和保护也是其上述作用的关键一环,特别是对分布其间的Lgr-5阳性肠干细胞的维护作用。大量研究显示,潘氏细胞和Lgr-5阳性肠干细胞构成了一个干细胞巢[5],前者可提供一些维护干性特征的关键受体或配体,如EGF、Dll4、Wnt3等,激活相应的细胞信号通路,维持后者的正常细胞功能[6]。潘氏细胞结构和功能的异常已被证实和炎性肠病等肠道疾患密切相关[6]。

2 结肠肿瘤干细胞、肿瘤干细胞巢及其组分研究

肿瘤干细胞,是指恶性肿瘤组织中具有极强自我复制能力和不对称分化能力的细胞亚群[7]。这些细胞亚群具有类似正常干细胞的自我更新和不对称分化能力,对常规放化疗等治疗措施具有很强的抵抗力,是恶性肿瘤发生、发展和转移的重要原因[8]。

2.1 结肠癌干细胞表面标志

结肠癌是实体肿瘤的典型代表,对结肠癌干细胞的研究目前较为充分,是实体肿瘤中较为成功的案例。对结肠干细胞的研究首先在于将其与普通肿瘤细胞进行分离,目前分离肿瘤干细胞的方法多样,最典型的方法是通过使用一些表面标志物。目前研究显示,借助一部分在正常干细胞中表达的分子,如CD133、CD44、ALDH-1、Lgr-5、Bmi-1等在肿瘤组织中分离出来细胞亚群具备肿瘤干细胞特性,见表 1。然而,由于肿瘤细胞的高度异质性,目前尚无法准确定义在这些标志物中何种标志物所代表的细胞亚群是真正的结肠癌干细胞,为进一步解决这个问题,部分学者尝试通过将上述标志物组合的方法进一步筛选;此外也有部分学者致力于发现新的标志物。值得注意的是,有研究发现某些控制正常肠道干细胞生命活动关键细胞信号通路的激活,如Wnt(以活化β-catenin为标志)[9]和Notch(以N1CD为代表)[10]在某些情况下可作为结肠癌干细胞的辅助标志。

表 1 部分结肠癌干细胞表面标记研究Table 1 Summary of some studies about stem cells surface markers in colorectal cancer

找到真正的结肠癌干细胞表面标志也许是一个漫长而复杂的过程,因为肿瘤时刻处在不断发展变化之中,除了潜在表面分子标记存在不断变化的可能外,这些分子内部的异构体也给研究造成了很多困难,比如CD44是胃肠道肿瘤干细胞泛性标志物,不仅用于标记胃癌干细胞[24],同样被用于标记结肠癌干细胞[6, 13-14],但对CD44异构体的研究表明,CD44v3、v8-10等均有可能进一步分选出更为准确的肿瘤干细胞,而最近一项研究证实CD44v6可能是结肠癌干细胞更为精确的标志物[22],可见分离鉴定“真正”的结肠癌干细胞仍然任重而道远。

2.2 肿瘤干细胞巢的分类

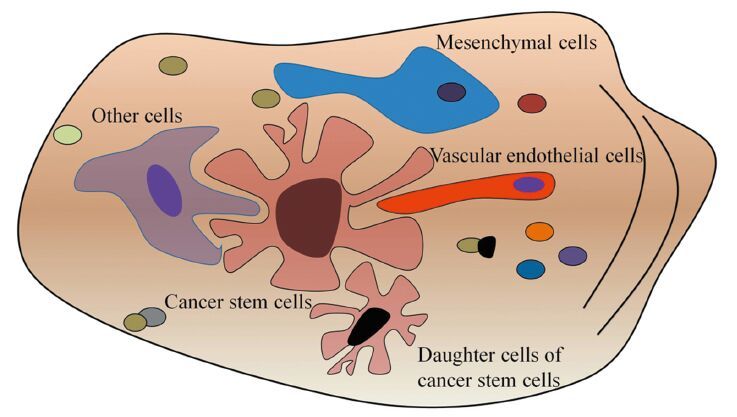

肿瘤干细胞的存在不能离开其所在的微环境,这种微环境包含多种细胞成分及不同刺激信号,对维持、保护、调节肿瘤干细胞功能具有关键作用,见图 2。值得注意的是随着肿瘤的不断进展,即使同一巢内,这些支持细胞成分可能也不尽相同。

对肿瘤干细胞巢的研究目前发现以下几类重要的干细胞巢,具有一定代表性:

(1)血管巢。新生微血管对肿瘤的发展、转移具有关键作用,对血管巢的研究表明肿瘤干细胞在位置上大多和微血管接近,在功能上能够分泌更多的血管内皮生长因子,诱导新生血管形成[25]。而对于这些新生微血管的内皮细胞来源也存在两种假设,一是来源于原有血管的出芽、增殖、迁徙;另一些研究显示,肿瘤干细胞可分化形成“瘤样内皮细胞”,直接参与血管巢和新生血管形成[26-27]。

(2)缺氧巢。缺氧巢在部分实体瘤中已得到证实,其中参与调节的因子主要有缺氧诱导因子1和2(HIF-1, HIF-2),但对两者的具体作用目前尚未得出一致结论。部分研究证实HIF-1α和HIF-2α均参与肿瘤干细胞的调节,基因敲除任意一个后均能导致肿瘤干细胞增殖障碍,但同时也有研究显示,相比HIF-1,HIF-2对肿瘤干细胞的作用更为关键,HIF-2α直接参与部分干细胞基因如Sox2、Oct4的调节[28]。

(3)炎性因子巢。近年来发现炎性因子在部分肿瘤中能刺激肿瘤干细胞增殖和维持其功能[29],尽管目前对肿瘤干细胞炎性因子巢的研究较少,但部分炎性因子如TGFβ、SDF1、bFGF和NO等对肿瘤干细胞的重要作用已经得到部分揭示,值得深入研究。

(4)免疫巢。免疫细胞和肿瘤细胞的相互关系至今在很多方面仍是一个谜,然而免疫细胞必定参与了肿瘤发生、发展和转移的诸多过程。近年来对脑胶质瘤的研究发现,肿瘤相关的巨噬细胞常位于CD133阳性的胶质瘤干细胞附近,肿瘤干细胞也被发现能分泌更多的炎性因子,诱导免疫细胞的趋化作用,这些被诱导到肿瘤干细胞周围的免疫细胞,对肿瘤对抗免疫、促进肿瘤转移等方面均有重要作用。

尽管名称各异,但也许这些“巢”在本质上是一致的,均是围绕在肿瘤干细胞周围的细胞成分,这些巢之间相互依存、关系紧密,如缺氧不仅可以诱导血管巢的形成[30],还可以招募到肿瘤浸润淋巴细胞,三者共同作用保护肿瘤干细胞,促进其增殖、转移[31-32]。值得注意的是,肿瘤干细胞和干细胞巢之间的关系并不是单向的,而是相互影响,相互促进[28]。随着研究的深入,对于肿瘤干细胞和肿瘤干细胞巢两者之间的关系产生了一个类似于“先有鸡还是先有蛋”的疑问,此外,不同的肿瘤干细胞巢中肿瘤干细胞的特性是否一致也是一个亟待回答的问题。

在结肠肿瘤干细胞研究中,尽管上述“巢”并未被完整论及,但目前已有初步研究提示这些“巢”的存在,如研究发现缺氧巢可保护CD133阳性结肠癌干细胞免于化疗打击[33]。此外,尽管在结肠癌中未得到证实,缺氧巢在胃癌研究中还被证实能促进胃癌干细胞转移[34]。而随着抗血管生成治疗、免疫治疗在结肠癌中的日趋成功,可以预见未来结肠癌干细胞巢研究必将成为热点。

3 以潘氏细胞为代表的肠上皮细胞在结肠肿瘤发展中的可能作用

结肠癌的发生发展是一个漫长的过程,涉及多个基因突变和细胞信号通路调控的紊乱,总体过程相对清晰,基本需要经过正常上皮→腺瘤(小、中、大)→腺癌这一过程,是理想的肿瘤研究模型。

3.1 潘氏细胞在结肠腺瘤中的作用

承前所述,由于人类肠道系统在胚胎发育及功能上的差异,导致其上皮细胞成分有所不同,在人肠上皮组织中,潘氏细胞主要分布于小肠,而在大肠中十分少见,部分动物如小鼠和大鼠中此类细胞的分布规律和人类相似。然而值得注意的是,在肠道肿瘤动物模型中,如APC基因敲除的鼠模型,肿瘤(大多是腺瘤)几乎均发生于小肠,极少发生于大肠;而人肠道肿瘤(腺瘤/腺癌)几乎均发生于结肠,极少见于小肠,这种差别导致在动物研究和人研究上的差异。尽管如此,潘氏细胞仍可在部分结肠肿瘤中发现(根据研究样本的不同,人结肠腺瘤中发现潘氏细胞的比例在21.4%~38.5%之间[35-37])。有意思的是动物模型中右半结肠可发现部分潘氏细胞样细胞[38];而人结肠腺瘤中潘氏细胞同样多位于右半结肠[36-37]。笔者所在课题组利用APC基因敲除小鼠制作结肠腺瘤模型,以EphB2、N1CD、β-Catenin等可辅助作为干细胞标志,发现潘氏细胞多数情况下位于腺瘤底部,更接近正常的腺窝,而该位置也是EphB2、N1CD表达最为明显的地方,位于肿瘤顶部相对恶性的部位(β-Catenin阳性)则较少有潘氏细胞存在;提示潘氏细胞在结肠肿瘤早期可能具有重要作用。值得注意的是在其他学者的研究中发现,在人结肠腺瘤中,即便组织学观察未能发现典型的潘氏细胞形态,但染色结果显示在这些腺瘤中存在潘氏细胞分化细胞或“瘤化”的潘氏细胞[35],以上结果均提示潘氏细胞在结肠肿瘤发生过程中至少在某个阶段(如腺瘤)可能起到关键作用。

3.2 潘氏细胞在结肠癌中的作用

在结肠肿瘤恶性转变的过程中,随着肿瘤恶性程度的加大,必将伴随着正常细胞成分的减少和异常细胞成分的增多,其中以潘氏细胞或其对应的细胞为代表。尽管前述部分结肠腺瘤中存在相对较高的潘氏细胞,但其比例在结肠腺癌中则微乎其微。这一现象同样在笔者所在课题组得到证实(待发表),我们发现即使在同一患者,其潘氏细胞数量在腺瘤和腺癌中也存在明显差别,在绝大多数结肠腺癌标本中,很少能发现潘氏细胞。而值得注意的是,健康者结肠中,对应潘氏细胞功能的是杯状细胞,此类细胞同时表达c-Kit(在动物模型中,潘氏细胞和杯状细胞均为c-Kit阳性细胞)[39]。众所周知,c-Kit细胞信号通路是一类通过自分泌或旁分泌起作用,维持干细胞功能的关键细胞信号通路。在人结肠癌研究中发现,部分分化的肿瘤细胞能保护ALDH-1阳性的肿瘤干细胞免于伊立替康打击[40];在人结肠癌细胞株中,c-Kit的异常表达能使结肠癌细胞更多表现出抗凋亡和容易侵袭的特性[41];进一步研究显示,分化的、能表达c-Kit的肿瘤细胞对于维持肿瘤干细胞至关重要[42]。以上研究提示,部分c-Kit阳性的细胞可能伴随人结肠肿瘤恶性转变始终,然而在此过程中,c-Kit阳性细胞可能同样经历了从正常细胞(如潘氏细胞、杯状细胞)到恶性细胞的转变,目前仍需进一步深入研究证实。

4 参与调控结肠肿瘤干细胞的细胞信号通路

Wnt、Notch和Heghog是调控正常干细胞的三大关键细胞信号通路,同时在肿瘤干细胞的研究中也具有十分关键的地位[43]。在结肠肿瘤干细胞巢中,这些细胞信号通路介导了潘氏细胞和肿瘤干细胞之间的许多关键生命活动,是重要的治疗靶向。例如正常情况下,潘氏细胞能为邻近的干细胞提供Wnt3a信号,后者对于干细胞标记—Lgr-5的表达为必须条件;在结肠肿瘤中,Wnt3a能通过激活Wnt通路促进结肠癌细胞形成血管拟态[44]、促进其上皮间质转化从而发生转移[45]。而Wnt基因敲除容易导致APC基因缺失的小鼠腺瘤和人结肠癌中潘氏细胞基因的表达,间接提示此类细胞在结肠肿瘤发生发展中的潜在作用[46]。此外,Notch通路同样对结肠癌干细胞具有关键调节作用,尽管在正常情况下潘氏细胞能提供Dll4配体激活Notch信号通路,在动物模型中c-Kit阳性细胞(包括潘氏细胞、杯状细胞)同样能通过提供Dll1、Dll4等配体激活Lgr-5阳性肠干细胞的Notch信号[39]。然而,目前尚缺乏在人结肠癌中对此类细胞提供相应的配体或受体激活结肠癌干细胞Notch信号通路的直接证据。

5 总结

结肠肿瘤是实体瘤的典型代表,是开展肿瘤干细胞巢研究的理想模型之一,遗憾的是尽管肿瘤干细胞巢的存在已经得到证实,但多数研究仅停留在“观察”层面,对其“来龙去脉”的研究尚不足,其在肿瘤发生、发展和转移中的关键作用尚未得到重视。我们认为,鉴于肿瘤干细胞巢中不同的细胞成分在维持、保护、促进肿瘤干细胞的作用,相信未来临床针对肿瘤干细胞巢的治疗定能进一步提高疗效,而肿瘤研究“巢”时代的开启,必将为最终攻克肿瘤带来新的曙光。

-

表 1 部分结肠癌干细胞表面标记研究

Table 1 Summary of some studies about stem cells surface markers in colorectal cancer

-

[1] Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2016, 66(2): 115-32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338

[2] Yan KS, Chia LA, Li X, et al. The intestinal stem cell markers Bmi1 and Lgr5 identify two functionally distinct populations[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109(2): 466-71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118857109

[3] van Es JH, Clevers H. Paneth cells[J]. Curr Biol, 2014, 24(12):R547-8. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.049

[4] Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2011, 9(5): 356-68. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2546

[5] Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts[J]. Nature, 2011, 469(7330): 415-8. doi: 10.1038/nature09637

[6] Nakamura K, Ayabe T. Paneth cells and stem cells in the intestinal stem cell niche and their association with inflammatory bowel disease[J]. Inflamm Regen, 2012, 32(2): 53-60. doi: 10.2492/inflammregen.32.053

[7] Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, et al. Cancer stem cells-perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2006, 66(19): 9339-44. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126

[8] Magee JA, Piskounova E, Morrison SJ. Cancer stem cells: impact, heterogeneity, and uncertainty[J]. Cancer Cell, 2012, 21(3): 283-96. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.03.003

[9] Vermeulen L, De Sousa E Melo F, Van dHM, et al. Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2010, 12(5): 468-76. doi: 10.1038/ncb2048

[10] Bu P, Wang L, Chen KY, et al. A miR-34a-Numb feedforward loop triggered by inflammation regulates asymmetric stem cell division in intestine and colon cancer[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2016, 18(2):189-202. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.006

[11] Ricci-Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E, et al. Identification and expansion of human colon-cancer-initiating cells[J]. Nature, 2007, 445(7123): 111-5. doi: 10.1038/nature05384

[12] O’Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S, et al. A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice[J]. Nature, 2007, 445(7123): 106-10. doi: 10.1038/nature05372

[13] Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, et al. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A , 2007, 104(24): 10158-63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104

[14] Chu P, Clanton DJ, Snipas TS, et al. Characterization of a subpopulation of colon cancer cells with stem cell-like properties[J]. Int J Cancer, 2009, 124(6): 1312-21. doi: 10.1002/ijc.v124:6

[15] Haraguchi N, Ohkuma M, Sakashita H, et al. CD133+CD44+ population efficiently enriches colon cancer initiating cells[J]. Ann Surg Oncol, 2008, 15(10): 2927-33. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0074-0

[16] Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T, et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells (SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis[J]. Cancer Res, 2009, 69(8): 3382-9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4418

[17] Pang R, Law WL, Chu AC, et al. A subpopulation of CD26+ cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity in human colorectal cancer[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2010, 6(6): 603-15. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.001

[18] Lin L, Liu Y, Li H, et al. Targeting colon cancer stem cells using a new curcumin analogue, GO-Y030[J]. Br J Cancer, 2011, 105(2): 212-20. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.200

[19] Zhang X. EphB2: a signature of colorectal cancer stem cells to predict relapse[J]. Protein Cell, 2011, 2(5): 347-348. doi: 10.1007/s13238-011-1058-6

[20] Kemper K, Prasetyanti PR, De Lau W, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against Lgr5 identify human colorectal cancer stem cells[J]. Stem Cells, 2012, 30(11): 2378-86. doi: 10.1002/stem.v30.11

[21] Gemei M, Mirabelli P, Di Noto R, et al. CD66c is a novel marker for colorectal cancer stem cell isolation, and its silencing halts tumor growth in vivo[J]. Cancer, 2013, 119(4): 729-38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27794

[22] Todaro M, Gaggianesi M, Catalano V, et al. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis[J]. Cell Stem Cell, 2014, 14(3): 342-56. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009

[23] Kantara C, O’Connell M, Sarkar S, et al. Curcumin promotes autophagic survival of a subset of colon cancer stem cells, which are ablated by DCLK1-siRNA[J]. Cancer Res, 2014, 74(9): 2487-98. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3536

[24] Takaishi S, Okumura T, Tu S, et al. Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44[J]. Stem Cells, 2009, 27(5): 1006-20. doi: 10.1002/stem.v27:5

[25] Ricci-Vitiani L, Pallini R, Biffoni M, et al. Tumour vascularization via endothelial differentiation of glioblastoma stem-like cells[J]. Nature, 2010, 468(7325): 824-8. doi: 10.1038/nature09557

[26] Alvero AB, Chen R, Fu HH, et al. Molecular phenotyping of human ovarian cancer stem cells unravels the mechanisms for repair and chemoresistance[J]. Cell Cycle, 2009, 8(1): 158-66. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.1.7533

[27] Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor[J]. Cancer Res, 2006, 66(16): 7843-8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010

[28] Filatova A, Acker T, Garvalov BK. The cancer stem cell niche(s): the crosstalk between glioma stem cells and their microenvironment[J]. Biochim Biophy Acta, 2013, 1830(2): 2496-508. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.10.008

[29] Ginestier C, Liu S, Diebel ME, et al. CXCR1 blockade selectively targets human breast cancer stem cells in vitro and in xenografts[J]. J Clin Invest, 2010, 120(2): 485-97. doi: 10.1172/JCI39397

[30] Rehn M, Olsson A, Reckzeh K, et al. Hypoxic induction of vascular endothelial growth factor regulates murine hematopoietic stem cell function in the low-oxygenic niche[J]. Blood, 2011, 118(6): 1534-43. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332890

[31] Collet G, El Hafny-Rahbi B, Nadim M, et al. Hypoxia-shaped vascular niche for cancer stem cells[J]. Contemp Oncol (Pozn), 2015, 19(1A): A39-43.

[32] Sceneay J, Chow MT, Chen A, et al. Primary tumor hypoxia recruits CD11b+/Ly6Cmed/Ly6G+ immune suppressor cells and compromises NK cell cytotoxicity in the premetastatic niche[J]. Cancer Res, 2012, 72(16): 3906-11. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3873

[33] Mao Q, Zhang Y, Fu X, et al. A tumor hypoxic niche protects human colon cancer stem cells from chemotherapy[J]. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2013, 139(2): 211-22. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1310-3

[34] Miao ZF, Wang ZN, Zhao TT, et al. Peritoneal milky spots serve as a hypoxic niche and favor gastric cancer stem/progenitor cell peritoneal dissemination through hypoxia-inducible factor 1α[J]. Stem Cells, 2014, 32(12): 3062-74. doi: 10.1002/stem.v32.12

[35] Joo M, Shahsafaei A, Odze RD. Paneth cell differentiation in colonic epithelial neoplasms: evidence for the role of the Apc/β-catenin/Tcf pathway[J]. Human Pathol, 2009, 40(6): 872-80. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.12.003

[36] Pai RK, Rybicki LA, Goldblum JR, et al. Paneth cells in colonic adenomas: association with male sex and adenoma burden[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2013, 37(1): 98-103. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318267b02e

[37] Wada R, Kuwabara N, Suda K. Incidence of Paneth cells in colorectal adenomas of Japanese descendants in Hawaii[J]. J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 1994, 9(3): 286-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1994.tb01727.x

[38] Mantani Y, Nishida M, Yuasa H, et al. Ultrastructural and histochemical study on the Paneth cells in the rat ascending colon[J]. Anat Rec (Hoboken), 2014, 297(8): 1462-71. doi: 10.1002/ar.v297.8

[39] Rothenberg ME, Nusse Y, Kalisky T, et al. Identification of a cKit+ colonic crypt base secretory cell that supports Lgr5+ stem cells in mice[J]. Gastroenterology, 2012, 142(5): 1195-1205. e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.006

[40] Emmink BL, Van Houdt WJ, Vries RG, et al. Differentiated human colorectal cancer cells protect tumor-initiating cells from irinotecan[J]. Gastroenterology, 2011, 141(1): 269-78. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.03.052

[41] Bellone G, Carbone A, Sibona N, et al. Aberrant activation of c-kit protects colon carcinoma cells against apoptosis and enhances their invasive potential[J]. Cancer Res, 2001, 61(5): 2200-6.

[42] Fatrai S, van Schelven SJ, Ubink I, et al. Maintenance of clonogenic KIT+ human colon tumor cells requires secretion of stem cell factor by differentiated tumor cells[J]. Gastroenterology, 2015, 149(3): 692-704. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.003

[43] Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, et al. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2011, 8(2): 97-106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196

[44] Qi L, Sun B, Liu Z, et al. Wnt3a expression is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes colon cancer progression[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2014, 33: 107. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0107-4

[45] Qi L, Song W, Liu Z, et al. Wnt3a Promotes the vasculogenic mimicry formation of colon cancer via wnt/β-catenin signaling[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2015, 16(8): 18564-79. doi: 10.3390/ijms160818564

[46] van Es JH, Jay P, Gregorieff A, et al. Wnt signalling induces maturation of Paneth cells in intestinal crypts[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2005, 7(4): 381-6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1240

下载:

下载: