文章信息

- 祝鹏,王伟军. 2014.

- ZHU Peng, WANG Weijun. 2014.

- 胰腺癌癌前病变基因研究进展

- Genetic Research Progress of Pancreatic Precancerous Lesions

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2014, 41(10): 1134-1138

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2014, 41 (10): 1134-1138

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2014.10.017

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2014-01-14

- 修回日期:2014-03-25

2013年,美国癌症协会评估了45 220名被诊断 为胰腺癌的美国人,将有38 460名患者因此疾病而 死亡[1]。尽管通过几十年的努力,其5年生存率仍 然只有大约5%左右。因缺少早期检测试验并且当 疾病仅局限于胰腺时,大多数患者并未出现临床 症状,导致直到疾病晚期才被诊断出来,而此时 肿瘤已转移至其他器官。为此,深入研究胰腺癌 癌前病变的基因突变事件,对于早期诊断胰腺癌 并寻找有效治疗方法能提供帮助。

1 胰腺癌癌前病变目前已证实主要有三种胰腺癌癌前病变[2,3,4], 胰腺上皮内瘤样病变(PanINs)、导管内乳头状 黏液性瘤(IPMNs)和黏液性囊性瘤(MCNs)。 研究表明,在82%的浸润性导管腺癌中发现有 PanINs病变[4],这表明绝大多数浸润性导管腺癌 是由PanINs发展而来的。与IPMNs和MCNs不同 的是,PanINs病变较难检测。因为IPMNs和MCNs 均是宏观的、肉眼可见的病变;而PanINs则是微 观的、肉眼不可见的病变[5]。PanINs起源于小型 终末胰管(< mm)[2]。基于形态学异型程度,可以将PanINs进一步归类。在PanIN-1病变中,正 常导管上皮细胞转化为高柱状上皮细胞并且可见 细胞内黏蛋白,而PanIN-2病变有显著的细胞学异 型性和核聚集。PanIN-3病变的特点是存在大量的 核聚集、核异型性、假乳头状生长、核分裂象和 管腔坏死[2, 6]。相比之下,导管内乳头状黏液性瘤 (IPMNs)和黏液性囊性瘤(MCNs)是肉眼可见 的囊性肿瘤。IPMNs发生在分泌黏蛋白的主胰管 或其分支,管腔内肿瘤的增长和大量黏蛋白分泌 导致了管腔系统的扩张。MCNs是典型的薄壁组织 内肿瘤且与胰腺导管系统不相连。组织结构上, MCNs的特征是黏蛋白上皮层与卵巢样基质相连。 除此之外,IPMNs和MCNs还具有一系列的形态学 特征,从低度到中度再到高度异型增生[3]。最终,胰 腺癌可能从上述任何一种癌前病变发展而来,但是 由PanINs发展而来的胰腺癌则更为常见[7]。

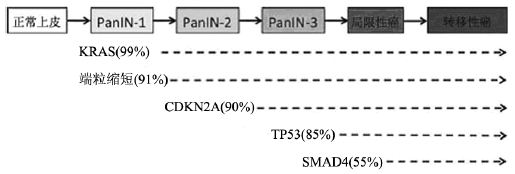

2 胰腺癌癌前病变的基因突变 2.1 胰腺上皮内瘤样变(PanINs)的基因突变根据病理形态学改变的进展程度可将PanINs 分为PanIN-1A、PanIN-1B、PanIN-2和PanIN-3。 在PanIN-1病变中,基因突变主要包括KRAS的激 活突变和端粒缩短[8,9]。PanIN-2病变主要表现的 是CDKN2A缺失,而在PanIN-3病变中,主要失活 的基因包括TP53、SMAD4和BRCA2[8]。当然, 这些基因突变事件也有例外的情况。例如,偶 有PanIN-1发生CDKN2A缺失突变或PanIN-2发生 TP53失活突变[8]。目前研究发现,由PanINs发展而 来的胰腺癌,其逐步演变过程有一套独特的“演变 模式”,并伴随有多种基因突变,见图 1。

2.1.1 KRAS在胰腺癌中,最早和最普遍发生的基因突变 是致癌基因KRAS发生激活突变[10]。至少有99%的 PanIN-1病变中KRAS发生了突变,这提示在大多 数胰腺癌癌变过程中,KRAS激活是一个重要的启 动步骤[11]。KRAS基因编码的三磷酸鸟苷(GTP) 结合蛋白,其作用是在多个细胞过程中充当一种 重要媒介,包括细胞存活、增殖和运动。在非激 活状态下,RAS与GDP结合。细胞外信号通过生 长因子受体使RAS与GDP发生解离,继而与GTP结 合。在GTP水解后,这些活性Ras-GTP复合物就失 去了活性。当KRAS基因发生激活突变时,Ras蛋 白自身的GTP酶活性丧失。因此,即使没有细胞 外信号,仍存在自身信号[12]。激活的Ras参与了一 些信号通路,包括RAF/丝裂原活化蛋白(MAP) 激酶通路以及磷酸肌醇-3激酶(PI3K)/ AKT信号 通路。在KRAS基因未发生突变的胰腺癌中观察到 另一种基因突变,即BRAF激活突变,这可使Ras- Raf-MAPK信号发生异常[13]。

2.1.2 CDKN2A绝大部分胰腺导管腺癌(95%)中CDKN2A均 发生了体细胞突变(失活),并伴随着p16/INK4A 蛋白的沉默表达[14]。CDKN2A基因有多个可变 的剪接位点,可表达多种蛋白质产物。例如, p14/ARF蛋白能隔离MDM2蛋白,从而帮助稳定 TP53。而p16/INK4A蛋白的作用是抑制细胞周期 蛋白和细胞周期蛋白依赖性激酶(CDKs)复合物 的形成,从而通过作用于细胞周期中G1期的检查 点而调节细胞周期进程[1516]。在约40%的病例中, CDKN2A因纯合子的缺失而发生失活。CDKN2A 缺失的另一个机制是基因内突变,即随后第二个 等位基因的缺失,引起了另外40%的突变。最近有 研究表明,当胰腺癌患者CDKN2A与KRAS基因同 时失活时,其生存期将会下降[17]。

2.1.3 TP53TP53基因的失活突变发生在更高级别的病变 中,即PanIN-3[18]。有高达85%的胰腺癌TP53发 生失活突变,最常见的基因内失活突变的机制是 第二个等位基因的缺失[19]。TP53作为一个重要 的调节器,在许多相互联系的细胞过程中发挥作 用,包括细胞凋亡、细胞周期进程和DNA修复。 在DNA损伤应答反应中,TP53基因能促进p21转 录。p21作为一种CDK抑制剂,可以与细胞周期 蛋白-CDK复合物结合,从而使细胞周期停滞在G1 期。TP53既可以调节促进细胞凋亡基因的转录, 也可以调节抑制细胞凋亡基因的转录。最近一项 研究表明,在67.4%胰腺癌和50%PanIN-3病变的 十二指肠胰液中检测到突变的TP53[20]。这提示检 测十二指肠胰液中是否存在突变的TP53,可能成为一种新的胰腺癌早期诊断方法。

|

| KRAS: kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; CDKN2A: cyclindependent kinase inhibitor 2A;TP53: tumor protein p53; SMAD4: SMAD family member 4 图 1 胰腺上皮内瘤样变(PanINs)的演变模式及其过程中发生突变的基因 Figure 1 Evolution mode of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanINs) and mutation genes during the process |

与TP53一样,SMAD4缺失也发生在高级别 病变中,即PanIN-3[21]。在通过转化生长因子β (TGF-β)信号转导通路而传导细胞外信号的过程 中,Smad4蛋白起着关键性作用。TGF-β通过调节 细胞增殖和分化,而在正常细胞中充当一个重要 的抑癌基因。这条通路的激活是从TGF-β配体与Ⅰ 型和Ⅱ型丝氨酸/苏氨酸激酶细胞表面受体结合开 始的。这将导致受体二聚化以及Ⅰ型受体激活, 从而使Smad2和Smad3蛋白发生磷酸化。Smad4蛋 白与磷酸化的Smad2/3蛋白质形成复合物,和他们 一起转移到细胞核内,与转录辅助因子联合,共 同调节基因的表达,参与各种重要的细胞过程, 包括细胞周期调控、细胞分化和增长[22]。在胰腺 导管腺癌中,SMAD4及之后TGF-β信号的缺失, 导致了TGF-β诱导的生长抑制作用丧失,这与患 者预后差和发生广泛转移密切相关[23,24]。正因为 SMAD4在胰腺癌中的重要作用,最近进行了一项 针对SMAD4失活突变的靶向治疗药物的Ⅱ期临床 试验[25],将来有望使SMAD4失活突变的胰腺癌患 者获得更好的治疗。

2.2 导管内乳头状黏液性瘤(IPMNs)和黏液性囊性瘤(MCNs)的基因突变虽然IPMNs和MCNs从低到中度再到高度异型 增生的形态学变化是众所周知的,但是对于这些 形态学的变化与基因突变事件之间的关系则鲜有 报道。因此,对于IPMNs和MCNs形成过程中基因 突变事件的研究正不断深入。

与PanINs相比,IPMNs和MCNs发生、发展过 程中的基因突变缺少很多特点[3]。与PanINs病变类 似,IPMNs和MCNs中也有KRAS和TP53突变,但 是发生的概率较低[26,27]。也发现有BRAF突变[28]。 由IPMNs病变进展而来的浸润性胰腺癌,可能出 现SMAD4表达的缺失,但很少在原位IPMNs中出 现。这与PanINs中的SMAD4不同,因为在30%的 PanIN-3病灶中存在表达缺失[21, 29]。相比之下,丝 氨酸/苏氨酸激酶(STK11/LKB1) 在IPMNs中发生 失活突变,但在PanINs中不发生突变[30]。作为一 种抑癌基因,STK11/LKB1的功能是在细胞凋亡、 新陈代谢和细胞极性中发挥关键作用[31]。10%的 IPMNs中存在PIK3CA激活突变,通过AKT发送致 癌信号[28]。然而,新的证据表明,这些突变可能 针对的是不同导管内肿瘤—导管内管状乳头状癌 (ITPN)[27]。最近,在IPMNs中发现了一个经常 出现的早期基因突变—GNAS突变[29,30]。超过40% 的IPMNs发生了GNAS突变。此外,25%的IPMNs 同时发生了GNAS和KRAS突变。在一个相似的研 究中[34],对被认为在癌症中经常发生突变的一组 基因进行分析,明确了GNAS在IPMNs囊液中的变 化。对IPMNs进行基因测序时发现,66%的IPMNs 发生了GNAS突变,超过一半的IPMNs同时发生了 GNAS和KRAS突变。

MCNs,胰腺癌中最少见的一种癌前病变,已 经明确的基因突变很少。人们已经注意到,在高度 异型增生的MCNs病变中存在KRAS和TP53突变[35]。 另据报道,由高度异型增生的MCNs进展而来的浸 润性癌中存在SMAD4缺失[27]。

3 全基因组外显子测序方法的研究使用候选基因分析—双脱氧测序法(Sanger) 初步阐明了KRAS、CDKN2A、TP53和TGF-β家族 基因突变。然而,近年来,新一代测序方法已被 使用来检查基因组的整个编码部分(即全基因组 外显子),其目标是明确一种肿瘤中所有基因体 细胞突变的情况[19]。通过揭示发生突变的“大山”和 “小山”基因,即分别发现肿瘤中发生突变频率高 和低的基因,反过来帮助创建一个更全面的基因 图谱[36]。

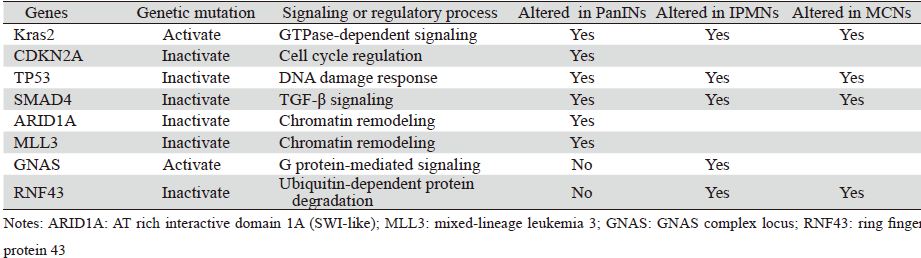

对用全基因组外显子测序方法获得的体细胞 基因突变数据进行进一步分类,显示它们对应着 12个核心信号通路:K-RAS信号通路、TGFβ信号 通路、JNK信号转导通路、整合素信号通路、Wnt/ Notch信号通路、Hedgehog信号转导通路、小GTP 酶信号通路、G1/S期转换调控信号通路、细胞凋 亡信号通路、DNA损伤控制信号通路、侵袭信号 通路和血友病细胞黏附信号通路[19]。这些通路, 很多是由参与了胰腺癌形成和发展的基因构成 的,如GTP酶依赖信号通路(Kras2)、DNA损伤 应答(TP53)[18]、细胞周期调控(CDKN2A)、 TGF-β信号(SMAD4)[37]。除了上述的这些核心 通路外,全基因组外显子测序的数据还表明,染 色质调控也在胰腺癌形成和发展中起着重要的作 用[38,39,40]。在PanINs演进过程中,参与染色质调控的 两个基因—ARID1A和MLL3均发生了突变,提示 它们可能通过染色质调控促进胰腺的癌变过程。 在MCNs和IPMNs中,人们发现了其他的信号通路 与调控过程中存在的基因突变。在G蛋白介导信号 通路中,GNAS基因发生激活突变,从而对G蛋白 的活性产生影响[33,34]。在泛素依赖蛋白水解过程中,RNF43基因发生失活突变,从而影响RNF43 蛋白产物作用的泛素依赖蛋白致瘤性[41],见表 1。 在每个患者中,对于一个特定的信号通路,基因 突变往往各不相同。这一发现可能有助于解释肿 瘤异质性,也能更深刻地理解为什么除了小部分 患者之外,针对信号通路中特定基因的针剂很少 获得尚佳的治疗效果。

|

胰腺癌是一种基因疾病,因此应该改变过去 对单一基因的研究,而转向基因间相互关系和相 互作用的研究。目前研究已经证实,胰腺癌主要 是从三种癌前病变中的一种进展而来的,并且每 一个病变的发生均与独特的基因突变有关。对 这些基因突变深入研究,不仅能加深对胰腺癌根 本起源的理解,还为改善早期诊断率提供了大量 机会,同时也提供了治愈这些癌前病变的机会。 此外,在胰腺癌癌前病变的研究中也应注重加强 各信号通路和调控过程与基因突变之间关系的研 究,尤其是12个核心信号通路与基因突变之间关 系的研究,以期发现新的靶点,开发针对性强、 不良反应小的靶向药物。最后,要阐明在患者疾 病进展中各个阶段相对应的信号通路,仍是一个 挑战。尽管如此,通过对肿瘤基因组进行更深入 的研究,也许将来能为我们提供一种对胰腺癌患 者进行全新的和个体化的治疗。

| [1] | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2013, 63(1):11-30. |

| [2] | Hruban RH, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, et al. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a new nomenclature and classification system for pancreatic duct lesions[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2001, 25(5): 579-86. |

| [3] | Matthaei H, Schulick RD, Hruban RH, et al. Cystic precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer[J]. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011, 8(3):141-50. |

| [4] | Andea A, Sarkar F, Adsay VN. Clinicopathological correlates of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: a comparative analysis of 82 cases with and 152 cases without pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma[J]. Mod Pathol, 2003, 16(10): 996-1006. |

| [5] | Cornish TC, Hruban RH. Pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia[J]. Surg Pathol Clin, 2011, 4(2): 523-35. |

| [6] | Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, et al. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2004, 28(8):977-87. |

| [7] | Gaujoux S, Brennan MF, Gonen M, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: changes in the presentation and management of 1,424 patients at a single institution over a 15-year time period[J]. J Am Coll Surg, 2011, 212(4):590-600; discussion 600-3. |

| [8] | Maitra A, Fukushima N, Takaori K, et al. Precursors to invasive pancreatic cancer[J]. Adv Anat Pathol, 2005, 12(2):81-91. |

| [9] | van Heek NT, Meeker AK, Kern SE, et al. Telomere shortening is nearly universal in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia[J]. Am J Pathol, 2002, 161(5):1541-7. |

| [10] | Shi C, Fukushima N, Abe T, et al. Sensitive and quantitative detection of KRAS2 gene mutations in pancreatic duct juice differentiates patients with pancreatic cancer from chronic pancreatitis, potential for early detection[J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2008, 7(3): 353-60. |

| [11] | Kanda M, Matthaei H, Wu J, et al. Presence of somatic mutations in most early-stage pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia[J]. Gastroenterology, 2012, 142 (4):730-3.e9. |

| [12] | Schubbert S,Shannon K,Bollag G. Hyperactive Ras in developmental disorders and cancer[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2007, 7(4):295-308. |

| [13] | Calhoun ES, Jones JB, Ashfaq R, et al. BRAF and FBXW7(CDC4, FBW7, AGO, SEL10)mutations in distinct subsets of pancreatic cancer: Potential therapeutic targets[J]. Am J Pathol, 2003, 163 (4):1255-60. |

| [14] | Li J, Poi MJ, Tsai MD. Regulatory mechanisms of tumor suppressor P16(INK4A) and their relevance to cancer[J]. Biochemistry, 2011, 50(25): 5566-82. |

| [15] | Larsson LG. Oncogene- and tumor suppressor gene-mediated suppression of cellular senescence[J]. Semin Cancer Biol, 2011, 21(6):367-76. |

| [16] | Kim WY, Sharpless NE. The regulation of INK4/ARF in cancer and aging[J]. Cell, 2006, 127 (2):265-75. |

| [17] | Rachakonda PS, Bauer AS, Xie H, et al. Somatic mutations in exocrine pancreatic tumors: association with patient survival[J]. PloS one, 2013, 8(4): e60870. |

| [18] | Murphy SJ, Hart SN, Lima JF, et al. Genetic alterations associated with progression from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia to invasive pancreatic tumor[J]. Gastroenterology, 2013, 145(5): 1098-109.e1 |

| [19] | Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses[J]. Science, 2008, 321(5897):1801-6. |

| [20] | Kanda M, Sadakari Y, Borges M, et al. Mutant TP53 in duodenal samples of pancreatic juice from patients with pancreatic cancer or high-grade dysplasia[J]. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2012, 11(6): 719-30. |

| [21] | Wilentz RE, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Argani P, et al. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: Evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression[J]. Cancer Res, 2000, 60(7):2002-6. |

| [22] | Siegel PM1, Massagué J. Cytostatic and apoptotic actions of TGFbeta in homeostasis and cancer[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2003, 3(11): 807-21. |

| [23] | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2009, 27 (11):1806-13. |

| [24] | Blackford A, Serrano OK, Wolfgang CL, et al. SMAD4 gene mutations are associated with poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2009, 15(14): 4674-9. |

| [25] | Crane CH, Varadhachary GR, Yordy JS, et al. Phase II trial of cetuximab, gemcitabine, and oxaliplatin followed by chemoradiation with cetuximab for locally advanced (T4) pancreatic adenocarcinoma: correlation of Smad4 (Dpc4) immunostaining with pattern of disease progression[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(22): 3037-43. |

| [26] | Hong SM, Park JY, Hruban RH, et al. Molecular signatures of pancreatic cancer[J]. Arch Pathol Lab Med, 2011, 135(6):716-27. |

| [27] | Yamaguchi H, Kuboki Y, Hatori T, et al. Somatic mutations in PIK3CA and activation of AKT in intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas[J]. Am J Surg Pathol, 2011, 35(12):1812-7. |

| [28] | Sch?nleben F, Qiu W, Bruckman KC, et al. BRAF and KRAS gene mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm/ carcinoma(IPMN/IPMC) of the pancreas[J]. Cancer Lett, 2007, 249(2): 242-8. |

| [29] | Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Klimstra DS, Adsay NV, et al. Dpc-4 protein is expressed in virtually all human intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: Comparison with conventional ductal adenocarcinomas[J]. Am J Pathol, 2000, 157(3):755-61. |

| [30] | Sahin F, Maitra A, Argani P, et al. Loss of Stk11/Lkb1 expression in pancreatic and biliary neoplasms[J]. Mod Pathol, 2003, 16(7):686-91. |

| [31] | Jansen M, Ten Klooster JP, Offerhaus GJ, et al. LKB1 and AMPK family signaling: The intimate link between cell polarity and energy metabolism[J].Physiol Rev,2009, 89(3):777-98. |

| [32] | Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2011, 3(92): 92ra66. |

| [33] | Furukawa T, Kuboki Y, Tanji E, et al. Whole-exome sequencing uncovers frequent GNAS mutations in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas[J]. Sci Rep, 2011, 1:161. |

| [34] | Wu J, Jiao Y, Dal Molin M, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of neoplastic cysts of the pancreas reveals recurrent mutations in components of ubiquitin-dependent pathways[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011, 108(52): 21188-93. |

| [35] | Kim SG, Wu TT, Lee JH, et al. Comparison of epigenetic and genetic alterations in mucinous cystic neoplasm and serous microcystic adenoma of pancreas[J]. Mod Pathol, 2003, 16(11): 1086-94. |

| [36] | Wood LD, Parsons DW, Jones S, et al. The genomic landscapes of human breast and colorectal cancers[J]. Science, 2007, 318(5853):1108-13. |

| [37] | Reid MD, Saka B, Balci S, et al. Molecular genetics of pancreatic neoplasms and their morphologic correlates: an update on recent advances and potential diagnostic applications[J]. Am J Clin Pathol, 2014, 141(2):168-80. |

| [38] | Jones S, Li M, Parsons DW, et al. Somatic mutations in the chromatin remodeling gene ARID1A occur in several tumor types[J]. Hum Mutat, 2012, 33(1): 100-3. |

| [39] | Shain AH, Giacomini CP, Matsukuma K, et al. Convergent structural alterations define SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin remodeler as a central tumor suppressive complex in pancreatic cancer[J].Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A,2012,109(5): E252-9. |

| [40] | Mann KM, Ward JM, Yew CC, et al. Sleeping Beauty mutagenesis reveals cooperating mutations and pathways in pancreatic adenocarcinoma[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109(16): 5934-41. |

2014, Vol. 41

2014, Vol. 41